Avian Influenza A Virus Infections in Humans

Avian Influenza A Virus Infections in Humans

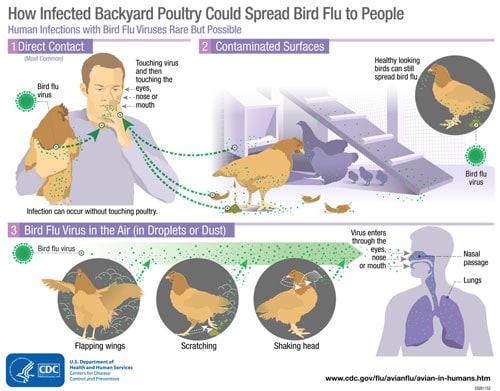

Although avian influenza A viruses usually do not infect people, rare cases of human infection with these viruses have been reported. Infected birds shed avian influenza virus in their saliva, mucous and feces. Human infections with bird flu viruses can happen when enough virus gets into a person’s eyes, nose or mouth, or is inhaled. This can happen when virus is in the air (in droplets or possibly dust) and a person breathes it in, or when a person touches something that has virus on it then touches their mouth, eyes or nose. Rare human infections with some avian viruses have occurred most often after unprotected contact with infected birds or surfaces contaminated with avian influenza viruses. However, some infections have been identified where direct contact was not known to have occurred. Illness in people has ranged from mild to severe.

Signs and Symptoms of Avian Influenza A Virus Infections in Humans

The reported signs and symptoms of avian influenza A virus infections in humans have ranged from mild to severe and included conjunctivitis, influenza-like illness (e.g., fever, cough, sore throat, muscle aches) sometimes accompanied by nausea, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and vomiting, severe respiratory illness (e.g., shortness of breath, difficulty breathing, pneumonia, acute respiratory distress, viral pneumonia, respiratory failure), neurologic changes (altered mental status, seizures), and the involvement of other organ systems. Asian lineage H7N9 and HPAI Asian lineage H5N1 viruses have been responsible for most human illness worldwide to date, including most serious illnesses and highest mortality.

Detecting Avian Influenza A Virus Infection in Humans

Avian influenza A virus infection in people cannot be diagnosed by clinical signs and symptoms alone; laboratory testing is needed. Avian influenza A virus infection is usually diagnosed by collecting a swab from the upper respiratory tract (nose or throat) of the sick person. (Testing is more accurate when the swab is collected during the first few days of illness.) This specimen is sent to a laboratory; the laboratory looks for avian influenza A virus either by using a molecular test, by trying to grow the virus, or both. (Growing avian influenza A viruses should only be done in laboratories with high levels of biosafety.)

For critically ill patients, collection and testing of lower respiratory tract specimens also may lead to diagnosis of avian influenza virus infection. However for some patients who are no longer very sick or who have fully recovered, it may be difficult to detect the avian influenza A virus in the specimen. Sometimes it may still be possible to diagnose avian influenza A virus infection by looking for evidence of antibodies the body has produced in response to the virus. This is not always an option because it requires two blood specimens (one taken during the first week of illness and another taken 3-4 weeks later). Also, it can take several weeks to verify the results, and testing must be performed in a special laboratory, such as at CDC.

CDC has posted guidance for clinicians and public health professionals in the United States on appropriate testing, specimen collection and processing of samples from patients who may be infected with avian influenza A viruses.

Treating Avian Influenza A Virus Infections in Humans

CDC currently recommends a neuraminidase inhibitor for treatment of human infection with avian influenza A viruses. CDC has posted avian influenza guidance for health care professionals and laboratorians, including guidance on the use of antiviral medications for the treatment of human infections with novel influenza viruses associated with severe disease. Analyses of available avian influenza viruses circulating worldwide suggest that most viruses are susceptible to oseltamivir, peramivir, and zanamivir. However, some evidence of antiviral resistance has been reported in Asian H5N1 and Asian H7N9 viruses isolated from some human cases. Monitoring for antiviral resistance among avian influenza A viruses is crucial and ongoing.

Preventing Human Infection with Avian Influenza A Viruses

The best way to prevent infection with avian influenza A viruses is to avoid sources of exposure. Most human infections with avian influenza A viruses have occurred following direct or close contact with infected poultry.

People who have had contact with infected birds may be given influenza antiviral drugs preventatively. While antiviral drugs are most often used to treat influenza, they also can be used to prevent infection in someone who has been exposed to influenza viruses. When used to prevent seasonal influenza, antiviral drugs are 70% to 90% effective. CDC has posted interim guidance for clinicians and public health professionals in the United States regarding follow-up and influenza antiviral chemoprophylaxis of persons exposed to birds infected with avian influenza A viruses.

Seasonal influenza vaccination will not prevent infection with avian influenza A viruses, but can reduce the risk of co-infection with human and avian influenza A viruses. It’s also possible to make a vaccine that can protect people against avian influenza viruses. For example, the United States government maintains a stockpile of vaccines to protect against some Asian avian influenza A H5N1 viruses. The stockpiled vaccine could be used if similar H5N1 viruses were to begin transmitting easily from person to person. Since influenza viruses change, CDC continues to make new candidate vaccine viruses as needed. Creating a candidate vaccine virus is the first step in producing a vaccine. See “Making a Candidate Vaccine Virus (CVV) for a Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (Bird Flu) Virus” for more information on this process.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario