Volume 24, Number 8—August 2018

Dispatch

Leptospirosis as Cause of Febrile Icteric Illness, Burkina Faso

On This Page

Sylvie Zida , Dramane Kania, Albert Sotto, Michel Brun, Mathieu Picardeau, Joany Castéra, Karine Bolloré, Thérèse Kagoné, Jacques Traoré, Aline Ouoba, Pierre Dujols, Philippe Van de Perre, Nicolas Méda, and Edouard Tuaillon

, Dramane Kania, Albert Sotto, Michel Brun, Mathieu Picardeau, Joany Castéra, Karine Bolloré, Thérèse Kagoné, Jacques Traoré, Aline Ouoba, Pierre Dujols, Philippe Van de Perre, Nicolas Méda, and Edouard Tuaillon

Abstract

Patients in Burkina Faso who sought medical attention for febrile jaundice were tested for leptospirosis. We confirmed leptospirosis in 27 (3.46%) of 781 patients: 23 (2.94%) tested positive using serologic assays and 4 (0.51%) using LipL32 PCR. We further presumed leptospirosis in 16 (2.82%) IgM-positive specimens.

Worldwide, approximately 1 million cases of human leptospirosis occur each year, resulting in ≈60,000 deaths (1). Although epidemiologic data for Africa are scarce, especially in semiarid and arid regions, some observations suggest that Leptospira spp. may be more prevalent than previously thought (2). In our study, we tested the hypothesis that leptospirosis is a cause of febrile jaundice in Burkina Faso.

We conducted the study at Centre Muraz (Bobo Dioulasso, Burkina Faso), a central reference laboratory responsible for the national surveillance of yellow fever. We identified confirmed leptospirosis cases in accordance with World Health Organization criteria (3) by symptoms consistent with leptospirosis and a single microscopic agglutination test (MAT) titer >1:400, by detection of Leptospira DNA by PCR, or both. We identified presumptive cases by symptoms consistent with leptospirosis and the presence of IgM. Specimens testing negative for serologic and PCR were considered negative. We retrospectively tested samples collected during January 2014–July 2015 from adults and children with jaundice and fever >38.5°C for the presence of IgM against Leptospira spp. using an in-house ELISA (Technical Appendix[PDF - 221 KB - 1 page]). We assessed serum that tested positive by ELISA for antibodies to Leptospira bacteria in the bacteriology laboratory of Montpellier University Hospital (Montpellier, France), using MAT to confirm the serologic results with a panel of 7 reference serogroups. We also tested for leptospirosis specimens for which a sufficient volume of serum was available by MAT in the French National Reference Center (Paris, France), using a larger panel of 24 serogroups, including the first 7 serogroups (Table 1). We performed real-time PCR for leptospirosis at Centre Muraz using PCR (PUMA LEPTO Kit; Omunis, Clapiers, France) targeting the lipL32 gene, which is present exclusively in pathogenic Leptospira spp. bacteria (4).

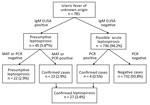

Figure 1. Flowchart used in study of leptospirosis in persons who sought medical attention for febrile jaundice, Burkina Faso. MAT, microscopic agglutination.

Of 781 samples, 45 (5.57%) tested positive for leptospira IgM by ELISA (Figure 1). Among those samples, 23 (2.94%) were positive by MAT (>1:400); consequently, these cases were considered to be confirmed. We considered 6 samples tested negative by MAT and 16 samples with MAT titer ranging from 1:100 to 1:200 (combined, 2.82%) to be presumptive cases. MAT results suggested the existence of multiple serogroups (Table 2), including reacting serogroups Australis, Ballum, Canicola, Grippotyphosa, Icterohaemorrhagiae, Pomona, and Sejroe. In addition, we performed MAT in the Leptospirosis National Reference Laboratory using a larger panel of serogroups applied to 33 ELISA-positive samples. Ten samples tested positive, and we confirmed the presence of all except the Ballum serogroup (data not shown). In 1 sample, we were able to identify Mini as an additional serogroup with a 1:400 titer. In addition to the serologic test, we confirmed leptospirosis cases by lipL32 PCR in 4/781 (0.51%) samples. All were negative for IgM, but 3 had optical density just above the positive threshold; signal to mean value of the negative controls was between 2 and 3 (data not shown). Hence, screening by serologic assay plus PCR identified a total of 27 (3.46%) cases of confirmed leptospirosis.

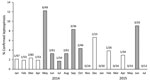

Figure 2. Confirmed cases of leptospirosis among samples received in Centre Muraz within the national network for yellow fever surveillance in Burkina Faso, January 2014–July 2015. White bars indicate months of the dry...

Median age for all patients was 20 years (interquartile range [IQR] 12–30 years); 61% were male (p = 0.65 by χ2 test). We observed the highest number of confirmed cases in the age group 10–19 years (data not shown), but the frequencies were not significantly different when cases were analyzed by age group (p = 0.41 by χ2 test). This observation was not unexpected because the population of Burkina Faso is young; almost two thirds of the population is <25 years of age. There was no particular gender distribution for persons with confirmed cases (13 women and 14 men; p = 0.33 by χ2 test). The repartition of confirmed, presumptive, and negative cases according to rainy season (May–mid-October) versus dry season from mid-October–April was unequal (p = 0.0035 by χ2 test), with a trend for a higher proportion of confirmed cases among samples received during the rainy season when compared with negative cases (p = 0.065 by χ2 test; Figure 2).

Our data were in line with a recent publication estimating that some of the West Africa countries, including those in semiarid regions, may have among the highest rates of disability-adjusted life years due to leptospirosis; in Burkina Faso, the rate may be 60–70/100,000 population/year (5). Leptospirosis infections have been reported in various parts of West Africa in humans (6–10). Studies in Senegal and Mali have shown that cattle, pigs, and sheep are frequently infected (11,12). Detection of leptospirosis was also recently reported in rodents in Niamey, Niger, especially in urban agricultural settings (13). In Burkina Faso, agricultural and livestock sectors represent 30% of the gross domestic product and are the backbone of the economy with ≈80% of the working-age population involved in these activities (14). Hence, human exposure to Leptospira spp. bacteria is probably frequent. Studies conducted in Ghana on patients with febrile illness without an obvious cause of disease found a frequency of 3.2% of confirmed leptospirosis cases and 7.8% of probable cases among icteric patients (2). In our study, half of the probable leptospirosis cases characterized by clinical signs consistent with leptospirosis and screened positive for Leptospira IgM were confirmed by MAT with a titer >1:400; two thirds had a titer >1:100 that may also be leptospirosis cases. Collecting and testing a convalescent serum sample might have confirmed the presumptive cases. In addition, the MAT has been shown to be less sensitive than IgM detection using ELISA, especially in acute-phase specimens (15). The low rate of molecular test positivity may be explained by the rapid disappearance of Leptospira spp. bacteria in the blood at the time the antibody response becomes detectable. Furthermore, transportation from the field to the centralized laboratory and storage at −20°C for >1 year before testing had a potentially adverse effect on the detection of low levels of LeptospiraDNA.

Because our study was retrospective and based on single sample testing, we probably overlooked some cases of leptospirosis. The lack of detail about clinical symptoms and evolution was a limitation of this study. We recruited participants with the presence of jaundice in addition to fever; hence, it is probable that among the cases of confirmed leptospirosis, severe forms were overrepresented.

MAT provided a general insight into existing Leptospira serogroups within Burkina Faso, suggesting multiple reservoirs. However, cautious interpretation is invited because of the high degree of cross-reactions among different serogroups, especially in acute-phase serum samples. In addition, 2 instances of seroreactivity against Ballum serogroup observed in the first MAT performed in the Montpellier University Hospital were not confirmed by using an enlarged panel in the National Center for Leptospirosis. This finding may be related to prolonged sample storage and multiple freeze/thaw cycles before testing in the national reference laboratory.

Leptospirosis appears to be an important cause of febrile jaundice in Burkina Faso, suggesting that leptospirosis is probably endemic in this country. Further studies are required to explore animal reservoirs and occupational risk factors associated with human leptospirosis. Awareness of leptospirosis among clinicians, funding for further study, and the possibility of conducting laboratory tests in the field are needed to clarify the extent of the problem in sub-Saharan Africa.

Dr. Zida works at the Muraz Center as a pharmacist. She is currently preparing a PhD at the University of Montpellier as a member of the U1058 INSERM team.

References

- Costa F, Hagan JE, Calcagno J, Kane M, Torgerson P, Martinez-Silveira MS, et al. Global morbidity and mortality of leptospirosis: a systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003898. DOIPubMed

- de Vries SG, Visser BJ, Nagel IM, Goris MG, Hartskeerl RA, Grobusch MP. Leptospirosis in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;28:47–64. DOIPubMed

- World Health Organization. Report of the second meeting of the Leptospirosis Burden Epidemiology Reference Group. Geneva: The Organization; 2011 [cited 2018 May 21]. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44588/1/9789241501521_eng.pdf

- Bourhy P, Bremont S, Zinini F, Giry C, Picardeau M. Comparison of real-time PCR assays for detection of pathogenic Leptospira spp. in blood and identification of variations in target sequences. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:2154–60. DOIPubMed

- Torgerson PR, Hagan JE, Costa F, Calcagno J, Kane M, Martinez-Silveira MS, et al. Global burden of leptospirosis: estimated in terms of disability adjusted life years. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0004122. DOIPubMed

- Awosanya EJ, Nguku P, Oyemakinde A, Omobowale O. Factors associated with probable cluster of leptospirosis among kennel workers in Abuja, Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2013;16:144. DOIPubMed

- Onyemelukwe NF. A serological survey for leptospirosis in the Enugu area of eastern Nigeria among people at occupational risk. J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;96:301–4.PubMed

- Ngbede EO, Raji MA, Kwanashie CN, Okolocha EC, Momoh AH, Adole EB, et al. Risk practices and awareness of leptospirosis in an abattoir in northwestern Nigeria. Sci J Vet Adv. 2012;1:65–9.

- Isa SE, Onyedibe KI, Okolo MO, Abiba AE, Mafuka JS, Simji GS, et al. A 21-year-old student with fever and profound jaundice. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e2534. DOIPubMed

- Houemenou G, Ahmed A, Libois R, Hartskeerl RA. Leptospira spp. prevalence in small mammal populations in Cotonou, Benin. ISRN Epidemiology. 2013. p. 1–8.

- de Vries SG, Visser BJ, Nagel IM, Goris MG, Hartskeerl RA, Grobusch MP. Leptospirosis in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;28:47–64. DOIPubMed

- Niang M, Will LA, Kane M, Diallo AA, Hussain M. Seroprevalence of leptospiral antibodies among dairy cattle kept in communal corrals in periurban areas of Bamako, Mali, West Africa. Prev Vet Med. 1994;18:259–65. DOI

- Dobigny G, Garba M, Tatard C, Loiseau A, Galan M, Kadaouré I, et al. Urban market gardening and rodent-borne pathogenic leptospira in arid zones: a case study in Niamey, Niger. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0004097. DOIPubMed

- France Ministry of Agriculture and Food. Agricultural policies around the world [in French]. 2016 [cited 2018 May 21]. http://agriculture.gouv.fr/burkina-faso

- Cumberland P, Everard CO, Levett PN. Assessment of the efficacy of an IgM-elisa and microscopic agglutination test (MAT) in the diagnosis of acute leptospirosis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61:731–4. DOIPubMed

.png)

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario