Scientists aim to defeat Middle East respiratory virus

The recent outbreak of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in South Korea has emphasized the urgent need to understand and counteract this deadly disease. The NIH and global partners are supporting multiple studies to pave the way for treatments and vaccines.

Photo by Dr. Pierre Rollin, courtesy of CDC

NIH is at the forefront of research on the Middle East

Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), which can be transmitted

by camels.

Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), which can be transmitted

by camels.

MERS was first identified in 2012 in Saudi Arabia and has killed about 40 percent of the more than 1,000 people diagnosed there. Although occurring mainly in the Arabian Peninsula and linked to contact with camels, travelers have helped spread the disease to 25 countries, including South Korea, where hospital-driven or other close human-to-human contact has fueled contagion. MERS can produce severe pneumonia and is particularly threatening to people already weakened by diabetes or other medical conditions.

Researchers have identified the MERS pathogen as a new coronavirus. This family of viruses was regarded as relatively benign in humans, producing no more than the common cold, until a mutated version triggered the 2003 epidemic of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS). Although that disease disappeared the next year as abruptly as it arose, scientists have no idea when, or if, it will resurface. In the meantime, MERS is persisting and taking more lives. Coronaviruses can evolve quickly and have a history of shifting between animal species.

Many of the humans struck by MERS worked or lived near camels, and the live virus has been detected in the animals' nasal droplets, milk, urine and flesh. One study of camel samples stored since 1983 showed a high rate of MERS antibodies, suggesting the virus has circulated for some time. Researchers supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) created a test for antibodies to a key MERS virus protein and found high levels in a type of bat and in dromedary camels.

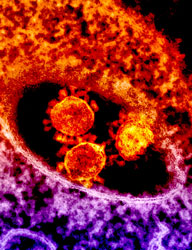

Image courtesy of NIAID

MERS-coronavirus

"What's very unclear is what proportion of the human cases we know about have been directly infected from camels or through exposure to other humans,” said Dr. Andrew Rambaut, of the Institute of Evolutionary Biology in Edinburgh, who receives support from Fogarty's Division of International Epidemiology and Population Studies and has studied MERS. "If we don't understand how the human cases are being infected, and what their exposure is, it’s difficult to intervene in a way that will eradicate the virus.”

To create a treatment for the disease, researchers are testing compounds that could interfere or stop virus replication, including antivirals used for hepatitis C - ribavirin and interferon-alpha 2b - which were successful in monkey cells, and kinase inhibitors, which can stop specific enzymes from functioning. In an NIAID-University of Maryland collaboration, researchers screened 290 compounds to see if they could inhibit growth of MERS and SARS viruses in the laboratory. They identified 27 candidates, including those normally used to treat cancer and psychiatric conditions, and are following up in mouse studies. Other potential treatments include chemicals that disarm or cause genetic disruptions in coronaviruses.

NIAID researchers and grantees are collaborating on potential vaccines to prevent MERS. One such candidate blocks a protein the virus needs to enter cells and corrupt immune defenses. Two other candidates focus on boosting the immune system response, one via a live but attenuated virus and another via the injection of viral DNA.

While researchers try to understand and thwart the spread of MERS, there is some small comfort it is less virulent than SARS, which rapidly infected 8,000 people from a single patient. "It seems unlikely MERS will spread successfully in the wider population,” Rambaut said. "It's had plenty of opportunity to do so, but has stayed relatively confined; each introduction tends not to persist for that long.”

Adapted from the July / August 2015 Global Health Matters article Scientists aim to defeat Middle East respiratory virus.

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario