Wednesday, December 9, 2015

WEDNESDAY, Dec. 9, 2015 (HealthDay News) -- New research suggests that more careful selection of patients could help improve the success rate of valves implanted into the lungs of people with emphysema.

The valves aim to improve breathing, allowing patients with the chronic lung disease to be more active and to perhaps survive longer. Previous research into the valves has been mixed, but the new Dutch study found that they work more effectively if physicians are more selective about which patients get them.

"The results are relatively impressive," said lung physician Dr. Gary Hunninghake, an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School in Boston. "These are benefits that physicians would want to get, and patients might feel better. This could result in people being more enthusiastic about this technique."

However, the valves come with a risk of serious side effects, the study authors noted, and the treatment appears to be expensive. It's also not clear whether the valves actually extend lives.

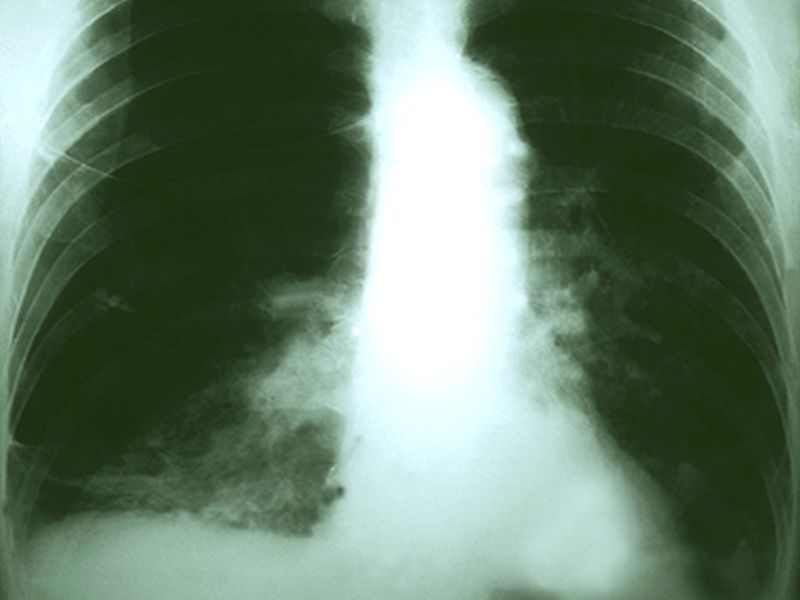

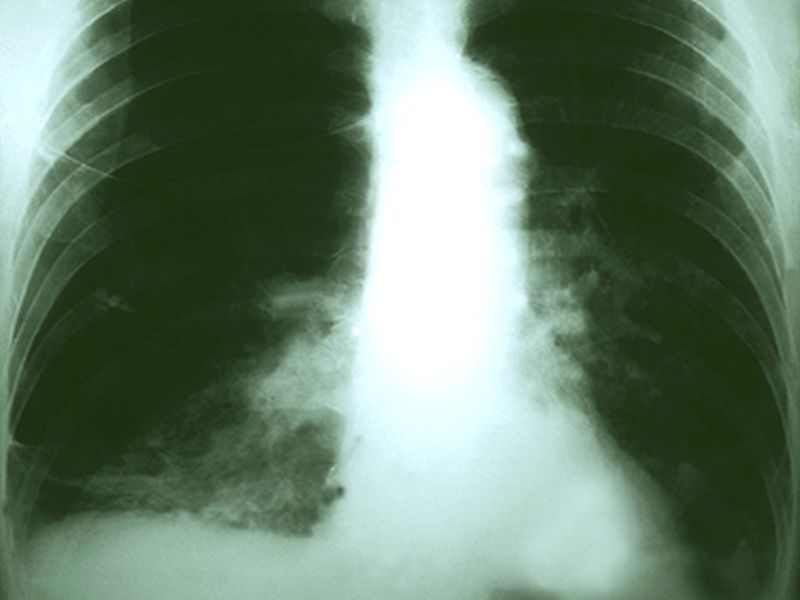

Emphysema is a type of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) that damages the airways and makes it difficult for people to breathe. Smoking is the main cause.

Treatment may help patients. But the prognosis can be grim for some people, with death expected within a few years.

In patients with emphysema, pockets filled with air can develop in the lungs and disrupt breathing, said Hunninghake, who was not involved in the new study. The pockets may push on other areas of the lung, causing it to expand in an unhealthy way.

Scientists have developed one-way "endobronchial valves," which are implanted in the lung and allow air to get out of the pockets but not get back into them, Hunninghake said. "It's a way of reducing the volume of these areas without doing surgery on them," he added, and patients may have several valves implanted.

Some physicians have wondered if they don't work as well in certain patients because air finds other ways to re-enter the pockets. In those patients, it appears that "the valve doesn't shut down the problem," Hunninghake said.

The new study aimed to eliminate these kinds of patients from the research. The study authors recruited 68 patients with severe emphysema, average age 59, to get valves implanted or regular treatment.

In general, those who received the valve treatment were able to breathe better and walk 243 feet farther in six minutes. Seventy-five percent of the patients who got the devices responded to the treatment, said study co-author Dr. Dirk-Jan Slebos, an associate professor with the department of pulmonary diseases at the University of Groningen, in the Netherlands.

According to Slebos, the surgery and follow-up treatment for a year in the Netherlands would cost the equivalent of about $22,000 to $33,000. The treatment is available in the United States, Hunninghake said, although he doesn't know its cost.

Will more doctors embrace this treatment? Maybe, Hunninghake said, if the findings can be confirmed. More research is underway, said study author Karin Klooster, a graduate student at the University of Groningen.

But doctors will have to consider the side effects, Hunninghake said, including those that occurred in this study -- an 18 percent chance of a collapsed lung and a 15 percent chance that the valve would have to be removed. It's possible, however, that the side effect rate will improve as surgeons get better at implanting the valves, he said.

Another lung specialist said the study raises hope for the treatment.

"Although the majority of people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease will not be suitable for this, it could still benefit a sizable minority and is a significant step forward," said Dr. Nicholas Hopkinson, a consultant chest physician with the Royal Brompton and Harefield NHS Foundation Trust in London. He said his own recent research with colleagues found similar results for the treatment over a three-month period.

The study was published Dec. 10 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

SOURCES: Gary Hunninghake, M.D., assistant professor, Harvard Medical School, Boston; Dirk-Jan Slebos, M.D., Ph.D., associate professor, department of pulmonary diseases, and Karin Klooster, graduate student, University of Groningen, the Netherlands; Nicholas Hopkinson, M.D., consultant chest physician, Royal Brompton and Harefield NHS Foundation Trust, London; Dec. 10, 2015, New England Journal of Medicine

HealthDay

Copyright (c) 2015 HealthDay. All rights reserved.

- More Health News on:

- Lung Diseases

.png)

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario