Scientists create synthetic tissue capable of synchronized beating

A team of chemists at the University of Bristol have developed a prototissue that is capable of synchronized beating when it is heated and cooled.

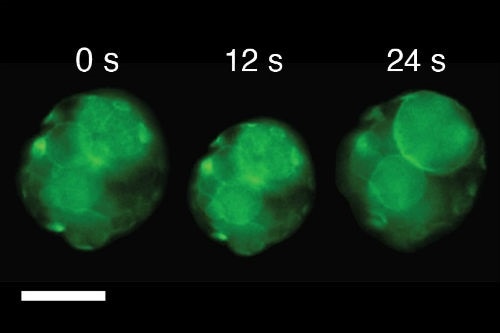

Snapshots of video images showing a single cluster of artificial cells exhibiting a single beat-like oscillation as the temperature was changed above or below 37 ⁰C; scale bar, 50 μm. (Image Credit: Dr. Pierangelo Gobbo, Uni of Bristol)

As reported in the journal Nature Materials, the development is the first chemically programmed approach to creating an artificial tissue and could have applications in healthcare in the future.

The finding could pave the way for the use of chemically-programmed artificial tissue to support the failure of living tissue and for treatments of certain diseases.

Until now, the development of tissues that imitate the functions of living cells has proved a difficult challenge in the field of synthetic biology.

However, Professor Stephen Mann and colleagues from Bristol’s School of Chemistry have now developed chemically-programmed protocells that interact and communicate with one another in a highly coordinated manner.

The team created two types of artificial cells that each had protein-polymer membranes with complementary anchoring groups on their surface.

They then organized a combination of the artificial cells into clusters to create self-supporting synthetic spheroids of tissue.

By ensuring the polymer used was capable of expanding or contracting as the temperature dropped or rose above 37 ⁰C, they found it was possible to make the tissue mimic beat-like oscillations.

After capturing enzymes within the synthetic cells, the team found they could increase the tissue’s functionality, modulate the beating and control the chemical signals moving in and out of the cells.

Mann says that the development bridges an important gap in bottom-up synthetic biology and should contribute to the development of new bioinspired materials that work at the interface between living tissues and their synthetic counterparts.

Source:

This news story is based on a press release by The University of Bristol and the research paper itself.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario