|

| MMWR Weekly Vol. 65, No. 48 December 09, 2016 |

| PDF of this issue |

Influenza Vaccination Coverage During Pregnancy — Selected Sites, United States, 2005–06 Through 2013–14 Influenza Vaccine Seasons

Weekly / December 9, 2016 / 65(48);1370–1373

Stephen Kerr, MPH1,2; Carla M. Van Bennekom, MPH1,2; Allen A. Mitchell, MD1,2; Vaccines and Medications in Pregnancy Surveillance System (View author affiliations)

View suggested citationSummary

What is already known about this topic?

Pregnant women and their infants are at increased risk for complications from influenza infection. Influenza vaccination during pregnancy has been found to protect pregnant women and their infants for several months after birth; thus, increasing vaccination rates among women who are pregnant or might become pregnant during the influenza season is a core public health and clinical practice goal. CDC has estimated that influenza vaccination in this population increased during the 2009–10 pandemic H1N1 vaccination season and increased modestly since then.

What is added by this report?

Among participants in the Birth Defects Study, which included pregnant women in New York and Massachusetts and the areas surrounding Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and San Diego, California, influenza vaccination coverage increased during the 2012–13 and 2013–14 influenza vaccination seasons, to 35% and 41%, respectively. Most influenza vaccines received by pregnant women were administered in physicians’ offices or clinics.

What are the implications for public health practice?

Incorporating counseling and education about influenza vaccination during pregnancy and administration of seasonal influenza vaccine into the routine management of pregnant women would offer a potential opportunity to increase influenza vaccination coverage among this vulnerable group and help prevent influenza-associated morbidity and mortality among pregnant women and their infants.

Stephen Kerr, MPH1,2; Carla M. Van Bennekom, MPH1,2; Allen A. Mitchell, MD1,2; Vaccines and Medications in Pregnancy Surveillance System (View author affiliations)

View suggested citation

Seasonal influenza vaccine is recommended for all pregnant women because of their increased risk for influenza-associated complications. In addition, receipt of influenza vaccine by women during pregnancy has been shown to protect their infants for several months after birth (1). As part of its case-control surveillance study of medications and birth defects, the Birth Defects Study of the Slone Epidemiology Center at Boston University has recorded data on vaccinations received during pregnancy since the 2005–06 influenza vaccination season. Among the 5,318 mothers of infants without major structural birth defects (control newborns) in this population, seasonal influenza vaccination coverage was approximately 20% in the seasons preceding the 2009–10 pandemic H1N1 (pH1N1) influenza season. During the 2009–10 influenza vaccination season, influenza vaccination coverage among pregnant women increased to 33%, and has increased modestly since then, to 41% during the 2013–14 season. Among pregnant women who received influenza vaccine during the 2013–14 season, 80% reported receiving their vaccine in a traditional health care setting, (e.g., the office of their obstetrician or primary care physician or their prenatal clinic) and 20% received it in a work/school, pharmacy/supermarket, or government setting. Incorporating routine administration of seasonal influenza vaccination into the management of pregnant women by their health care providers might increase coverage with this important public health intervention.

Influenza poses a serious threat to public health. In the United States, millions of persons are sickened, and thousands die each year of influenza and influenza-related illness (2,3). Because pregnant women infected with influenza are at increased risk for severe illness, hospitalization, and complications (4), in 2004, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) updated their guidance with the recommendation that “women who will be pregnant during the influenza season” receive the seasonal influenza vaccine, regardless of pregnancy trimester (5). In the influenza seasons after the ACIP recommendation (2006–07 through 2008–09), CDC estimated influenza vaccination coverage among pregnant women to be approximately 15%; coverage did not exceed 30% until it increased markedly (to 38%) during the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic (6). The most recent CDC study on influenza vaccination among pregnant women (2015–16 influenza season) reported overall coverage of 50%; an estimated 14% of women were vaccinated ≤5–6 months before pregnancy and 36% were vaccinated during pregnancy (7).

In 2006, the Birth Defects Study began to inquire specifically about receipt of influenza vaccine and other vaccines during pregnancy. The current report describes secular trends in seasonal influenza vaccination coverage among pregnant women in the Birth Defects Study during the nine seasons from 2005 through 2014, along with the settings in which pregnant women received their vaccinations.

The Birth Defects Study conducted surveillance during 1976–2015 using a case-control methodology described previously (8). Infants with major structural birth defects (cases) were identified at study centers that, for the present analysis, included participating hospitals in the areas surrounding Boston, Massachusetts, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and San Diego, California, as well as birth defects registries in New York and Massachusetts. Infants without structural defects (controls) were randomly selected each month from study hospitals’ discharge lists or statewide vital statistics records. Within 6 months of delivery, mothers of case and control infants were invited to participate in a computer-assisted telephone interview conducted by trained study nurses. Data were collected on demographic characteristics, lifestyle factors, reproductive history, illnesses, and medications used from 2 months before the last menstrual period (LMP) through the end of pregnancy. Medication data included prescription and over-the-counter drugs and, for pregnancies that began in 2005 or later, any vaccines received during pregnancy. Women were asked to provide an exact date of vaccination or, if the vaccination date was not available, a range of possible dates, along with the setting or facility where the vaccine was administered (e.g., doctor’s office/prenatal clinic, workplace, school, pharmacy/supermarket, or government site). All women who reported receiving a vaccine were asked to provide a release allowing study personnel to contact the vaccine provider to validate their vaccine report. If vaccine records were not available, the maternal report was accepted (9).

This analysis of influenza vaccination coverage was limited to pregnancies in control women that overlapped with the 2005–06 through 2013–14 influenza vaccine seasons. Each influenza vaccine season was defined as beginning on August 1 and continuing through July 31 of the following year. Among women who reported receiving influenza vaccine during pregnancy, the exact date of vaccination obtained from the vaccination record was used to assign the influenza vaccination season during which vaccine was received, if the record was available; otherwise, the vaccination date the woman provided or the midpoint of the reported date range was used. To ensure equivalent opportunity for vaccination during each influenza season, the range of LMP dates among women who received each season’s vaccine was identified; women whose LMPs fell within that range but did not receive the vaccine were included in the analysis as unvaccinated women.

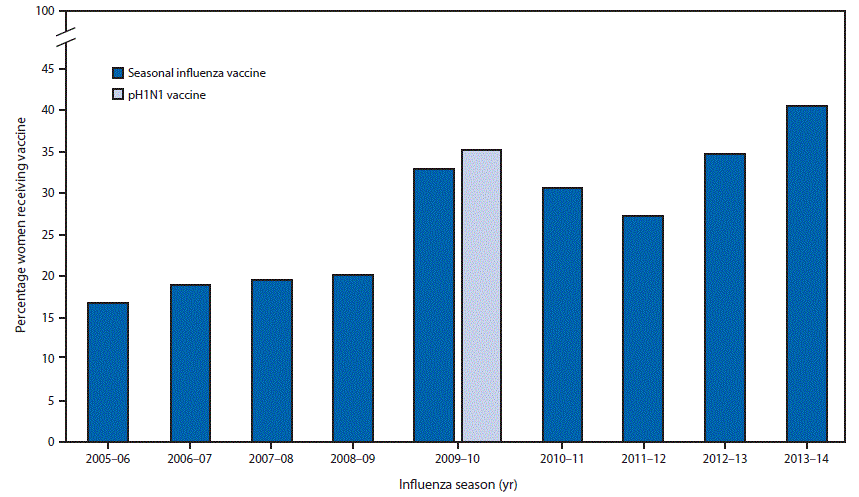

Among the 5,318 pregnant women who participated in the study during the nine influenza vaccination seasons (2005–06 through 2013–14), 73% of vaccine doses administered were validated by provider records; the remaining 27% were ascertained by maternal self-report. Influenza vaccination coverage varied by season (Figure). During the 2009–10 influenza vaccination season, pH1N1 vaccine became available late in the season as a separate product; in subsequent seasons, pH1N1 vaccine has been included as a component of seasonal influenza vaccines. During the 2005–06 through 2008–09 influenza vaccination seasons, coverage ranged from 17%–20%. Seasonal influenza vaccination coverage increased to 33% during the 2009–10 season and to 35% for the pH1N1 vaccine. Coverage declined slightly during the next two influenza vaccination seasons (2010–11 and 2011–12), to 31% and 27% respectively; subsequently, in the 2012–13 and 2013–14 seasons, coverage increased again to 35% and 41%, respectively.

Overall, 79% of influenza vaccinations received by pregnant women were administered in a traditional health care setting (e.g., the office of their obstetrician or primary care physician or their prenatal clinic). During the nine influenza vaccination seasons, the proportion of vaccine doses received by pregnant women in these settings increased from 73% during the 2005–06 season to 80% during the 2013–14 season. The proportion of vaccine doses received in pharmacy/supermarket settings increased from 4% in 2005–06 to 8% in 2013–14; the proportion of doses received at work or school decreased from 23% in 2006–07 to 10% in 2013–14.

Discussion

During the 2005–06 through 2008–09 influenza vaccination seasons, coverage with the seasonal influenza vaccine among pregnant women in the Birth Defects Study sites was approximately 20%. Coverage increased during the 2009–10 pH1N1 pandemic influenza vaccine season to approximately 33%, declined slightly in the next two seasons, and increased again during the 2012–13 and 2013–14 seasons, to 35% and 41%, respectively.

Approximately 21% of vaccine doses were administered in settings where the dose might not be recorded in the patient’s medical record; thus, studies that obtain coverage estimates exclusively from medical record databases might underestimate actual coverage, and, in etiologic studies, this approach could lead to potential misclassification of vaccination status.

The findings in this report are subject to at least three limitations. First, this analysis identified vaccination during pregnancy only, whereas other studies included doses received ≤5–6 months before pregnancy; therefore, the coverage estimates from this analysis might be lower than estimates obtained in other studies. Second, influenza vaccination histories were ascertained by self-report and could be subject to misclassification; however, maternal reports in the Birth Defects Study were previously found to be accurate within a given trimester for 83% of women in this population (10), and 73% of reported vaccinations in the current study were confirmed by the vaccine providers’ records. Finally, the study sites included in this analysis are not representative of the U.S. population and small numbers might have affected season-to-season variability.

Seasonal influenza vaccination during pregnancy among women living in the area of the Birth Defects Study sites more than doubled during the nine influenza vaccination seasons covered in this analysis, and although the trend is encouraging, coverage still falls far short of the 2016 ACIP recommendation that all pregnant women who are or might become pregnant during flu season be vaccinated. CDC found that during the 2015–16 influenza season, 63% of pregnant women whose health care provider recommended and offered influenza vaccination received the vaccine compared with 38% who received a recommendation but no offer, and only 13% of pregnant women who received no recommendation (7). Incorporating counseling and administration for seasonal influenza vaccine into the routine management of pregnant women can offer the best option for increasing influenza vaccination coverage among this vulnerable group to prevent influenza-associated morbidity and mortality among pregnant women and their infants.

Acknowledgments

The VAMPSS team (includes the authors, Carol Louik, ScD, Christina Chambers, PhD, Kenneth L. Jones, MD, Michael Schatz, MD); Dawn Jacobs, Fiona Rice, Rita Krolak, Christina Coleman, Kathleen Sheehan, Clare Coughlin, Moira Quinn, Laurie Cincotta, Mary Thibeault, Susan Littlefield, Nancy Rodriquez-Sheridan, Ileana Gatica, Laine Catlin Fletcher, Carolina Meyers, Joan Shander, Julia Venanzi, Michelle Eglovitch, Mark Abcede, Darryl Partridge, Casey Braddy, Shannon Stratton, staff members, Massachusetts Department of Public Health Center for Birth Defects Research and Prevention and the Massachusetts Registry of Vital Records; Charlotte Druschel, Deborah Fox, staff members, the New York State Health Department; Christina Chambers, Kenneth Jones, University of California, San Diego; William Cooper, Vanderbilt University Medical Center; medical and nursing staff members, Boston Children's Hospital, Kent Hospital, Southern New Hampshire Medical Center, Women & Infants' Hospital, Abington Memorial Hospital, Albert Einstein Medical Center, Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children, Bryn Mawr Hospital, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Christiana Care Health Services, Lankenau Hospital, Lancaster General Hospital, Temple University Health Sciences Center, Reading Hospital & Medical Center, Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, Rady Children’s Hospital San Diego, Kaiser Zion Medical Center, Palomar Medical Center, Pomerado Hospital, Scripps Mercy Hospital, Scripps Memorial Hospital-Chula Vista, Scripps Memorial Hospital-Encinitas, Scripps Memorial Hospital-La Jolla, Sharp Chula Vista Hospital, Sharp Grossmont Hospital, Sharp Mary Birch Hospital, Tri-City Medical Center, University of California-San Diego Medical Center; Margaret Honein, Dixie Snider, Robert Glynn, James Mills, Elizabeth Conradson Cleary, Joseph Bocchini, Peter Gergen, VAMPSS Vaccine and Asthma Advisory Committee; Jo Schweinle, Tanima Sinha, Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Lauri Sweetman, Sheila Heitzig, American Academy of Asthma, Allergy, & Immunology; mothers who participated in the study.

Corresponding author: Stephen Kerr, skerr1@bu.edu.

1Slone Epidemiology Center at Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts; 2Vaccines and Medications in Pregnancy Surveillance System (VAMPSS).

References

- Tapia MD, Sow SO, Tamboura B, et al. Maternal immunisation with trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine for prevention of influenza in infants in Mali: a prospective, active-controlled, observer-blind, randomised phase 4 trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2016;16:1026–35. CrossRef PubMed

- Reed C, Kim IK, Singleton JA, et al. Estimated influenza illnesses and hospitalizations averted by vaccination—United States, 2013–14 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014;63:1151–4. PubMed

- Thompson M, Shay D, Zhou H, et al. . Estimates of deaths associated with seasonal influenza—United States, 1976–2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2010;59:1057–62. PubMed

- Jamieson DJ, Theiler RN, Rasmussen SA. Emerging infections and pregnancy. Emerg Infect Dis 2006;12:1638–43. CrossRef PubMed

- Harper SA, Fukuda K, Uyeki TM, Cox NJ, Bridges CB; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Prevention and control of influenza: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 2004;53(No. RR-06). PubMed

- Fiore AE, Uyeki TM, Broder K, et al. Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep 2010;59(No. RR-08). PubMed

- CDC. Flu vaccination coverage among pregnant women—United States, 2015–16 flu season. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2016. http://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/pregnant-coverage_1516estimates.htm

- Louik C, Kerr S, Van Bennekom CM, et al. Safety of the 2011–12, 2012–13, and 2013–14 seasonal influenza vaccines in pregnancy: Preterm delivery and specific malformations, a study from the case-control arm of VAMPSS. Vaccine 2016;34:4450–9. CrossRef PubMed

- Louik C, Chambers C, Jacobs D, Rice F, Johnson D, Mitchell AA. Influenza vaccine safety in pregnancy: can we identify exposures? Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2013;22:33–9. CrossRefPubMed

- Jacobs D, Louik C, Dynkin N, Mitchell AA. Accuracy of maternal report of influenza vaccine exposure in pregnancy. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2011;20:S360.

FIGURE. Receipt of seasonal influenza vaccine by pregnant women* participating in the Birth Defects Study† — United States, 2005–06 through 2013–14 influenza seasons

FIGURE. Receipt of seasonal influenza vaccine by pregnant women* participating in the Birth Defects Study† — United States, 2005–06 through 2013–14 influenza seasons

* Women participating as controls (i.e., mothers of infants without a structural birth defect).

† Participating hospitals in areas surrounding Boston, MA; Philadelphia, PA; and San Diego, CA; and birth defects registries in New York and Massachusetts.

.png)

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario