Volume 26, Number 1—January 2020

Research Letter

Rare Case of Enteric Ancylostoma caninum Hookworm Infection, South Korea

On This Page

Figures

Downloads

Article Metrics

Abstract

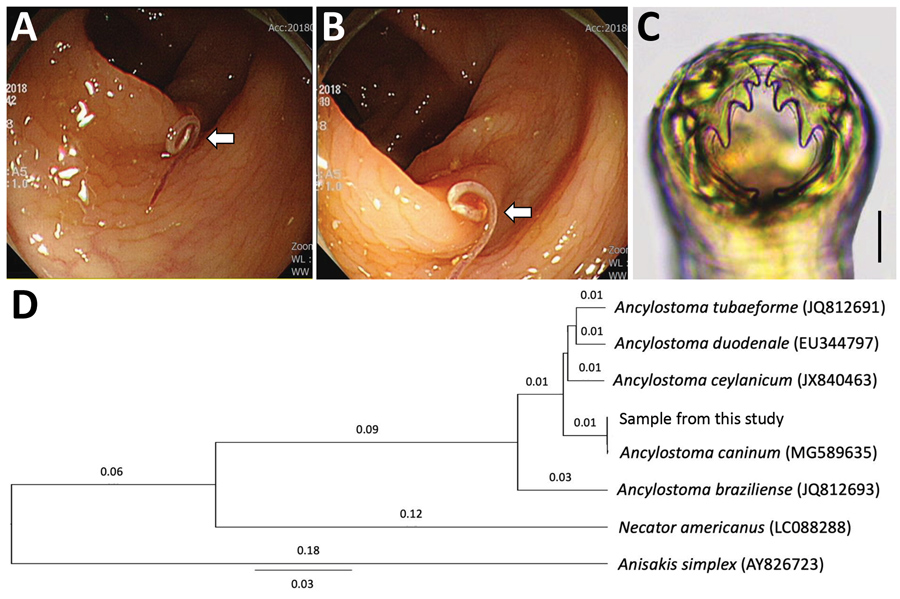

A 60-year-old man from South Korea underwent a colonoscopy. A juvenile female worm showing 3 pairs of teeth in the buccal cavity was recovered from the descending colon. Partial sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer region showed 100% identity with Ancylostoma caninum, the dog hookworm.

Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus are the 2 major hookworm species causing human enteric infections around the world. However, Ancylostoma ceylanicum, which infects mainly dogs and cats, has become an emerging hookworm species causing human enteric infections in Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands (1,2). Another hookworm species, Ancylostoma caninum, which infects dogs and rarely cats, can also infect humans, possibly as cutaneous larva migrans (3) or enteric infections in association with eosinophilic enteritis (4–6). Human enteric A. caninum infection has been known mainly in Australia (4,5). However, 2 sporadic human cases (serologically positive but not based on recovery of worms) were reported in the United States (6), and samples from 3 schoolchildren in South Africa were detected molecularly to be egg positive (7).

We recently encountered a case of A. caninum infection in a 60-year-old man who visited a health checkup center and demonstrated a moderate degree of eosinophilia. During colonoscopy, a nematode parasite (female) was found and removed with forceps. The worm was then morphologically and molecularly confirmed to be a dog hookworm, A. caninum.

The patient had no subjective symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, dark feces, or weight loss. However, laboratory examinations showed some abnormalities in liver functions and blood values: total bilirubin 2.11 mg/dL (reference range 0.2–1.57 mg/dL), gamma-glutamyltransferase 238 IU/L (reference range 0–56 IU/L), total serum IgE 1,265 IU/mL (reference range 0–87 IU/mL), and peripheral blood eosinophilia 7.5% (reference range 0%–0.45%). Other blood results were within normal limits: hemoglobin 14.6 g/dL, lymphocytes 26.6%, monocytes 8.0%, basophils 0.9%, and neutrophils 57.0%. The patient owned a dog for 5 years and had regular contact with the dog but had never traveled abroad.

Colonoscopy showed a single threadlike moving worm at the descending colon (Figure, panels A, B). Under magnifying endoscopy, the worm looked like a nematode hooking its head into the colonic mucosa. We removed the worm and sent it to the laboratory. The worm was cleared in lactophenol before microscopic examinations and was found to be a juvenile female hookworm, 12 mm in length and 0.36 mm in width, morphologically identified as A. caninum based on the presence of its characteristic 3 pairs of teeth in the buccal cavity (Figure, panel C). We treated the patient with a 3-day course of albendazole.

After morphologic examinations, we cut the middle part of the nematode and preserved it in 70% ethanol for molecular studies. We isolated genomic DNA from the worm segment using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (QIAGEN, ), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. We partially amplified the internal transcribed spacer 1 and 5.8S rDNA regions (312 bp) using the standard PCR protocol with 2x MasterMix (MGmed, ) and 10 pmol of forward and reverse primers to detect Ancylostoma species (8). The PCR product obtained was directly sequenced at Macrogen Inc. (Seoul, South Korea). The results revealed 100% homology with the sequences of A. caninum deposited in GenBank (accession no. MG589635) (Figure, panel D). Our sample also revealed 98.1% homology with A. duodenale, 97.1% with A. ceylanicum, and 92.4% with Ancylostoma braziliense.

Human enteric A. caninum infection is extremely rare except in northeastern semitropical regions of Queensland, Australia, where several hundred cases in the form of eosinophilic enteritis have been detected (5). Most of these human cases came from a typical suburban environment; in Townsville district, Queensland, 50% of the population have a dog at home, and 69% of adults regularly engage in high-risk behavior, such as walking barefoot on damp grass frequented by dogs (5). Human infections with infective-stage larvae appear to occur through a cutaneous route (5) or ingestion of infective larvae (9).

Signs of human infections include ambiguous abdominal pain that may or may not be associated with eosinophilia (5). This patient had no remarkable subjective symptoms except for circulating eosinophilia and markedly elevated total serum IgE. Some abnormalities were noted in liver functions, including slightly elevated total bilirubin and markedly elevated gamma-glutamyltransferase levels. However, these findings seem to have little meaning in relation to A. caninum infection.

The worm from this case was a juvenile female that did not contain eggs in its uterus. Thus, our result agrees with previous reports from Australia (4,5) that these worms do not mature sufficiently to cause infection; they survive probably for only a few weeks. However, recent studies in South Africa (7) and India (10) detected hookworm eggs in human feces; these were molecularly confirmed to be A. caninum. This finding apparently showed that A. caninum hookworms can fully develop into egg-producing adults within the human intestine, although occurrence may be rare.

Our study is epidemiologically noteworthy because human enteric A. caninum infection may also occur in countries in Asia where this hookworm species is common among dogs, as well as in Australia, the United States, India, and South Africa. Even symptomatic infections with A. caninum hookworms may often be missed or misdiagnosed as other conditions or diseases.

Dr. Jung is a senior researcher at the Institute of Parasitic Diseases, Korea Association of Health Promotion, Seoul, South Korea. His primary research interest is parasite fauna study. He also studies toxoplasmosis of the central nervous system in humans and animals.

Acknowledgment

We thank the staff in Jeonbuk Branch of Korea Association of Health Promotion, Seoul, South Korea, who helped with the management of this patient.

References

- Hsu YC, Lin JT. Images in clinical medicine. Intestinal infestation with Ancylostoma ceylanicum. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:

e20 . - Bradbury RS, Hii SF, Harrington H, Speare R, Traub R. Ancylostoma ceylanicum hookworm in the Solomon Islands. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23:252–7.

- Liu Y, Zheng G, Alsarakibi M, Zhang X, Hu W, Lu P, et al. Molecular identification of Ancylostoma caninum isolated from cats in southern China based on complete ITS sequence. BioMed Res Int. 2013;2013:868050.

- Prociv P, Croese J. Human eosinophilic enteritis caused by dog hookworm Ancylostoma caninum. Lancet. 1990:335:1299–302.

- Prociv P, Croese J. Human enteric infection with Ancylostoma caninum: hookworms reappraised in the light of a “new” zoonosis. Acta Trop. 1996;62:23–44.

- Khoshoo V, Craver R, Schantz P, Loukas A, Prociv P. Abdominal pain, pan-gut eosinophilia, and dog hookworm infection. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1995;21:481–3.

- Ngcamphalala PI, Lamb J, Mukaratirwa S. Molecular identification of hookworm isolates from stray dogs, humans and selected wildlife from South Africa. J Helminthol. 2019:e39.

- Traub RJ, Robertson ID, Irwin P, Mencke N, Thompson RC. Application of a species-specific PCR-RFLP to identify Ancylostoma eggs directly from canine faeces. Vet Parasitol. 2004;123:245–55.

- Landmann JK, Prociv P. Experimental human infection with the dog hookworm, Ancylostoma caninum. Med J Aust. 2003;178:69–71.

- George S, Levecke B, Kattula D, Velusamy V, Roy S, Geldhof P, et al. Molecular identification of hookworm isolates in humans, dogs and soil in a tribal area in Tamil Nadu, India. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:

e0004891 .

Figure

Cite This ArticleOriginal Publication Date: 12/10/2019

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario