04/03/2017 | |

The FDA has approved the first drug ever for the rare skin cancer, Merkel cell carcinoma, and updated data show an improved tumor response rate and that patients’ tumors continued to respond for at least a | |

Avelumab Becomes First Approved Treatment for Patients with Merkel Cell Carcinoma

April 3, 2017, by NCI Staff

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the immunotherapy drug avelumab(Bavencio®) for the treatment of some patients with a rare and aggressive skin cancer known as Merkel cell carcinoma. It is the first FDA-approved treatment for this disease.

The approval was based on results from a clinical trial that included 88 patients with metastaticMerkel cell carcinoma who had previously been treated with chemotherapy. Now, the researchers who conducted the trial have presented new results from the trial with longer follow-up.

The new data, based on a median follow-up of 16.4 months, show a small increase in the overall response rate compared with 6 months of follow-up, from 31% to 33%.

Ten patients had complete responses and 19 had partial responses, Howard L. Kaufman, M.D., of the Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey, reported on April 3 at the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) annual meeting in Washington, DC.

Nearly all of the patients who initially responded to the drug continued to respond, with most responses lasting for more than a year, Dr. Kaufman noted. At the time of the data analysis, 21 of the responses were ongoing, and the median duration of response had not been reached.

The study authors estimate that 74% of patients with Merkel cell carcinoma who respond to avelumab will have a response that lasts a year or longer.

“We have seen dramatic responses in some patients within 6 weeks, and, just as important, the responses appear to be durable,” Dr. Kaufman said. Moreover, he continued, “the drug appears to be relatively safe. The main side effects were fatigue and infusion-related reactions, which were manageable."

Avelumab “represents an important advance in the management of a cancer that is often fatal and historically has had no effective treatments,” Dr. Kaufman added.

Most of the patients in the study had been “heavily pretreated” with chemotherapy, noted Suzanne Topalian, M.D., of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, who moderated a press briefing on immunotherapies at the AACR meeting but was not involved in the trial.

But even in patients with difficult-to-treat disease, Dr. Topalian continued, there was “a very nice response” to avelumab.

A New Immunotherapy

The FDA’s approval is for adults and pediatric patients 12 years and older who have metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma, including patients who have not been treated with chemotherapy previously.

In the United States, Merkel cell carcinoma is diagnosed in fewer than 2,000 individuals each year, most of them elderly or with weakened immune systems. Chemotherapy can shrink Merkel cell tumors, but the cancer usually begins growing again within 6 months.

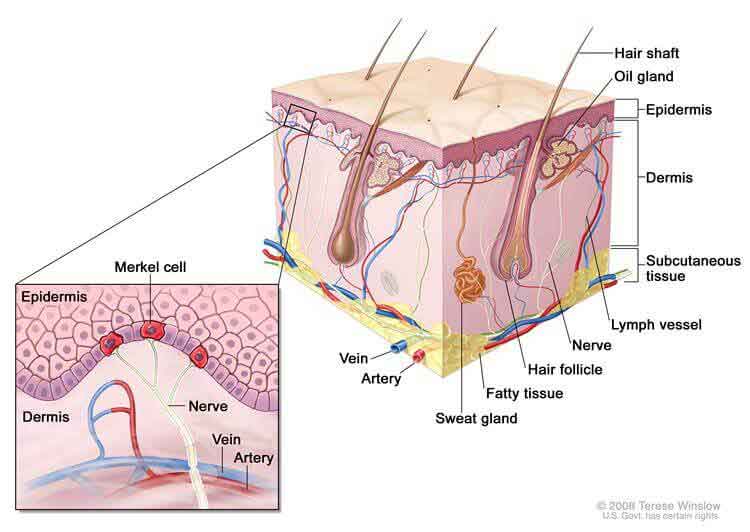

Some Merkel cell tumors have high levels of DNA damage caused by sun exposure. Most tumors are caused by a virus, called Merkel cell polyomavirus, that is often present in healthy skin but in rare cases can result in cancer.

The association with the virus and the fact that tumor incidence is much higher in immune-suppressed populations contributed to the decision in 2013 by researchers at NCI and their colleagues to test an immunotherapy in patients with the disease.

“Virus-positive tumors are a natural target for the immune system,” said James Gulley, M.D., Ph.D., of NCI’s Center for Cancer Research (CCR), who coordinated the first-in-human clinical trial of avelumab. He also provided advice about the clinical development of avelumab to the drug’s maker, EMD Serono, a biopharmaceutical division of Merck KGaA.

Avelumab belongs to a group of immunotherapy drugs known as immune checkpoint inhibitors. These agents “remove the brakes” on the immune system, allowing immune cells to kill cancer cells more effectively. The protein targeted by avelumab, called PD-L1, is overexpressed in many Merkel cell tumors.

Avelumab is an antibody and may also attack tumor cells through a second mechanism, called antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity, noted Dr. Gulley. In this type of immune reaction, certain white blood cells kill tumor cells that are coated with the drug.

Clinical Trial Results

Since the launch of the phase I trial at NCI about 5 years ago, the drug has been tested in more than 1,700 patients around the world with various types of cancer, including melanoma and gastric, lung, and ovarian cancers.

The phase II JAVELIN Merkel 200 study, which led to the FDA approval and was funded by Merck KGaA and Pfizer, is still recruiting patients. To assess the effects of avelumab in previously untreated patients with Merkel cell carcinoma, Dr. Kaufman and his colleagues have enrolled several dozen patients on another cohort of this clinical trial.

Preliminary results from this new study are consistent with results from the JAVELIN trial, showing that the drug shrinks tumors and is well tolerated, according to Dr. Kaufman.

In 2016, another phase II trial showed that pembrolizumab, which targets a checkpoint protein called PD-1, was effective in some patients with Merkel cell carcinoma. That trial also included patients who had not received chemotherapy previously.

Next Steps

Now that a treatment for Merkel cell carcinoma is available for the first time, Dr. Kaufman said there is an opportunity to increase awareness about the disease, particularly among physicians. Some patients visit multiple doctors before receiving a proper diagnosis, which is especially concerning because in some cases the disease can progress very rapidly, he noted.

For researchers, understanding why some patients respond to avelumab and others do not will be important, said Isaac Brownell, M.D., Ph.D., of CCR’s Dermatology Branch, who treated patients on the avelumab trial at the NIH Clinical Center.

“We need to figure out how to increase the response rates further so that even more patients will benefit,” Dr. Brownell said. “We need to determine if we can combine avelumab with other drugs to help even more patients.”

Dr. Gulley agreed. “We have just begun to see the approval data for this drug as a single agent,” he said, “but I truly believe that it is the combination approaches that will prove even more effective in a range of different tumors.”

Although no combination trials for patients with Merkel cell carcinoma have been established yet, the researchers have been discussing possibilities. Combinations will likely be a topic of discussion at a workshop on Merkel cell carcinoma that will take place in early 2018 and will be sponsored by NCI’s Rare Tumor Initiative.

“The goal of the meeting will be to develop a consensus on how to best move forward with advancing research on treatment for this disease,” said Dr. Brownell.

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario