Wednesday, August 3, 2016

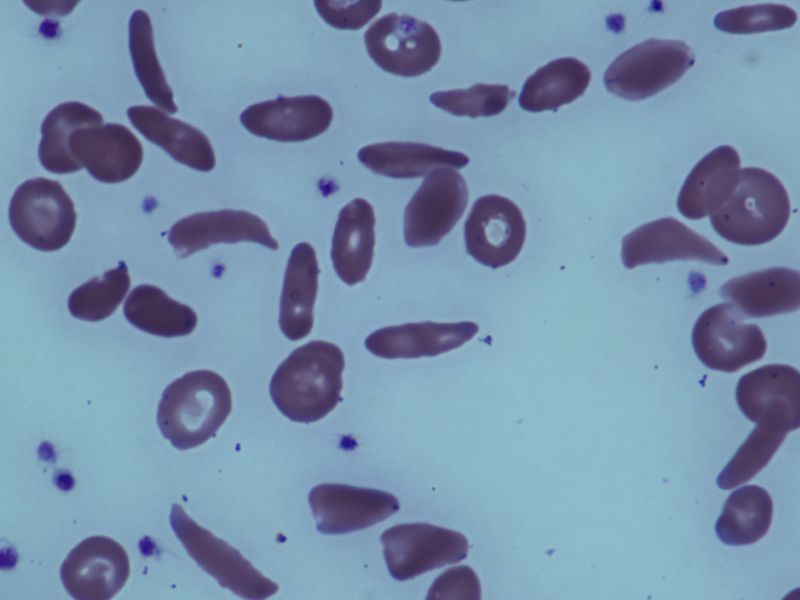

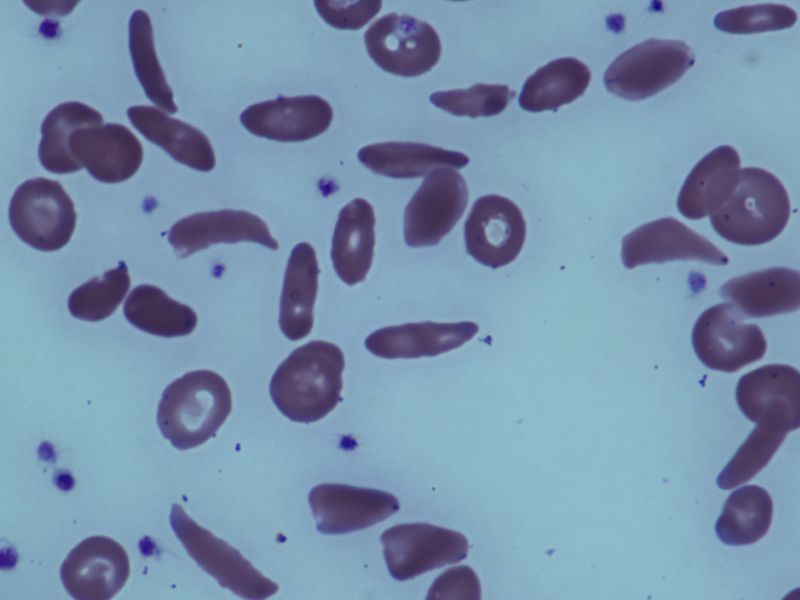

WEDNESDAY, Aug. 3, 2016 (HealthDay News) -- New research challenges the long-held belief that people with sickle cell trait, who are born with only a single copy of the sickle cell gene variant, are at risk of premature death.

People with the sickle cell gene variant do not have sickle cell disease, a blood disorder that shortens life span and causes sudden episodes of severe pain. People with the disease carry two copies of the gene, one from each parent.

In the first-of-its-kind study, researchers followed nearly 48,000 black American soldiers on active duty in the U.S. Army over a four-year period. All had undergone tests for the genetic trait.

"What we can say with confidence is that there's no evidence that it increases mortality in this Army population, and that's incredibly reassuring," said study co-author Lianne Kurina. She's an associate professor of medicine at Stanford University School of Medicine in Palo Alto, Calif.

Previous studies have linked sickle cell trait to sharply higher risks of sudden death among black military recruits and black football players on National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division 1 teams. These studies traced some of the deaths to heat stroke, heat stress and "exertional rhabdomyolysis" -- muscle deterioration due to extreme physical exertion.

The notion that sickle cell trait increases death risk has led to mandatory screening by some organizations, including the U.S. Air Force, U.S. Navy and the NCAA, the study authors noted.

The American Society of Hematology continues to believe that there's a lack of data to support the presumption that mandatory screening will save lives, according to Dr. Alexis Thompson, the society's vice president.

"These findings suggest that sickle cell trait alone does not increase an individual's risk of sudden death," said Thompson, a pediatric hematologist at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago.

Experts say the Army's use of "universal precautions" -- which require active duty soldiers to drink plenty of fluids, build up to strenuous exercise and rest when it's hot -- made a difference.

"These results provide a strong impetus for all organizations with individuals who perform intense exercise to develop formalized protocols for universal precautions," said Dr. Rakhi Naik. She is an assistant professor of medicine in the hematology division at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

Thompson added that the evidence in this paper "underscores the benefit that these measures can have for all individuals, not just those with sickle cell trait."

Sickle cell trait rarely causes symptoms of sickle cell disease, says the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The concern with sickle cell trait is muscle breakdown due to intense exercise, often in extreme temperatures.

Although uncommon, exertional rhabdomyolysis can be fatal, Kurina said. That's why the research team focused on that outcome.

While there was no significant difference in death risk, researchers did find that black soldiers with sickle cell trait were 54 percent more likely than their counterparts without the trait to suffer exertional rhabdomyolysis.

That level of risk is on par with the higher risks associated with tobacco use and obesity, the researchers found.

The absolute risk was quite small. Just over 1 percent of black soldiers with sickle cell trait in the study developed exertional rhabdomyolysis, compared to 0.8 percent of their counterparts without sickle cell trait, Kurina said.

For the new analysis, researchers had access to medical and administrative data on all active duty soldiers in the United States.

The researchers identified 391 exertional rhabdomyolysis events during the study period. Risk rose with age, but was much lower for women than for men.

Only one death was observed among soldiers with exertional rhabdomyolysis, and it involved a soldier without sickle cell trait, the study authors noted.

The study, published Aug. 3 in The New England Journal of Medicine, was funded by the U.S. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in collaboration with the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences.

SOURCES: Lianne Kurina, Ph.D., associate professor, medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, Calif.; Rakhi Naik, M.D., assistant professor, medicine, hematology division, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore; Alexis Thompson, M.D., pediatric hematologist, Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago; Aug. 3, 2016, The New England Journal of Medicine

HealthDay

Copyright (c) 2016 HealthDay. All rights reserved.

News stories are provided by HealthDay and do not reflect the views of MedlinePlus, the National Library of Medicine, the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, or federal policy.

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario