Precision medicine the theme at world's biggest cancer conference

New era of targeted treatment that will extend survival rates detailed at American Society of Clinical Oncology meeting

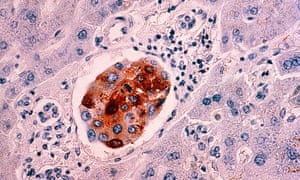

A new era of cancer treatment is beginning in which patients get drugs matched specifically to their tumour, according to scientists at the world’s biggest cancer conference in Chicago.

Precision or personalised medicine, as it is called, “is about targeting treatment so that it’s more powerful, while reducing the toxicity, so there are fewer side-effects”, said Prof Roy Herbst, chief of medical oncology at Yale Cancer Center. “At the moment it’s more like using a cannonball to kill an ant – and creating a whole lot of damage at the same time.”

The talk at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (Asco) annual meeting this weekend is of longer survival and fewer toxic effects through this approach, which is being made possible by advances in genetic profiling of the tumour itself.

A number of studies will present results at Asco showing that this approach can extend survival in many different cancer types, while a study being launched in the UK – if all goes as experts hope – could result in up to 7,000 women being spared the toxic side-effects of chemotherapy, while saving the NHS an estimated £17m.

The UK trial, called Optima, is being run by University College London and Cambridge University and funded by Cancer Research UK. Beginning in the summer, it will recruit 4,500 women with breast cancer, whose tumours will be genetically tested as soon as they are diagnosed to establish which will respond to chemotherapy and which will not.

“It will be a significant step forward,” said Dr Robert Stein, a consultant in breast cancer at UCL. “In every area of cancer treatment we have largely functioned on a one-size-fits-all basis because we didn’t have tools to do any better.”

Of the 50,000 or so women diagnosed with breast cancer in the UK each year, about 40%, or 20,000, are currently given chemotherapy but only half of them do well as a result of it; in the other half, the benefit is unclear. The researchers hope to find out which of the latter group actually need chemotherapy.

“We would expect to reduce chemotherapy within the trial population by about two-thirds,” said Stein. “We are looking at between 5,500 and 7,000 fewer a year being treated with chemotherapy than are currently treated. It’s quite a big deal.”

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario