Understanding “Chemobrain” and Cognitive Impairment after Cancer Treatment

Understanding “Chemobrain” and Cognitive Impairment after Cancer Treatment

For decades, cancer survivors have described experiencing problems with memory, attention, and processing information months or even years after treatment. Because so many of these survivors had chemotherapy, this phenomenon has been called "chemobrain" or "chemofog," but researchers say those terms don't always fit the varied impairments experienced by these patients.

Why cancer treatment-related cognitive impairment occurs isn't fully understood. But recent research, including the largest study to date of breast cancer survivors to focus on this problem, aims to find the factors that might predict which patients will have cognitive impairment after treatment and to identify what can be done to lessen its impact.

A Frequent Problem

Although cognitive changes have been associated with treatment for many kinds of cancer, recent research has focused on cognitive changes in breast cancer survivors. In an update on the state of the science in 2012, Tim Ahles, Ph.D., of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and his colleagues reported that studies of breast cancer survivors found that 17% to 75% of these women experienced cognitive deficits—problems with attention, concentration, planning, and working memory—from 6 months to 20 years after receiving chemotherapy.

According to Julia Rowland, Ph.D., director of NCI's Office of Cancer Survivorship, for a long time many women who brought up these issues with their doctors found their concerns dismissed. But now, "people are finally taking it very seriously," she said. Doctors are realizing that "you have to understand what the consequences of therapy are and that very few if any of our treatments are entirely benign."

Early researchers assumed that cognitive problems were a result of chemotherapy alone. More recent research has suggested that the combination of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy, or even hormonal therapy alone, may cause cognitive change.

"From many sources of data, we now know patients experience impairments not just after chemo, but after surgery, radiation, hormonal therapy," and other treatments, said Patricia Ganz, M.D., an oncologist and director of Cancer Prevention and Control Research at UCLA's Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center.

From many sources of data, we now know patients experience impairments not just after chemo, but after surgery, radiation, hormonal therapy, and other treatments.

In one study, Dr. Ganz and her colleagues gave 53 breast cancer survivors and 19 matched healthy women a comprehensive neurocognitive test and took measures of mood, energy level, and self-reported cognitive functioning. They found that the survivors who’d had adjuvant chemotherapy performed significantly worse than those who'd had surgery only, with the worst performance among those who’d received chemotherapy and the antiestrogen drug tamoxifen (Nolvadex®).

One challenge in studying these issues has been that many cancer survivors who report cognitive difficulties still perform within the normal range on neuropsychological tests. "You assess people's memory, and it tends to be fine," said Dr. Ahles. "But because of problems with attention and being able to sort out relevant information, it's harder for them to store information properly."

Imaging studies conducted by Dr. Ganz and others show that, despite performing within the normal range on these tests, women who report cognitive challenges are still struggling. For example, in one study, a set of identical twins—one who had received chemotherapy treatment for breast cancer and one who did not have cancer—was evaluated with self-reported measures, neuropsychological tests, and MRI. The results showed small differences in the neuropsychological tests, but the twin who had cancer treatment had substantially more self-reported cognitive complaints. Imaging tests in this twin showed greater recruitment of brain areas during working memory processing.

These patients "have to work harder," Dr. Ganz said. "Often they'll get the answer right on a neuropsychology test, but it takes much more effort for them to come up with that," than people who haven't been exposed to treatment.

Investigating Different Reactions to Treatment

But why do some cancer survivors experience cognitive decline after treatment while others don't? "Clearly there's a subset of people who aren't affected," said Dr. Rowland. "So the question is: Who are they? What are the factors there?"

And do these cognitive issues sometimes develop prior to cancer treatment? In a 2008 study, more than 20% of patients with breast cancer had lower cognitive performance at the pretreatment assessment than would be expected for their age and education, and other studies have had similar findings. This shows that "it's not just the treatment that you get but what you bring to the diagnosis that increases your risk," Dr. Ahles said.

To explore these and other factors, a team led by Michelle Janelsins, Ph.D., of the University of Rochester's Wilmot Cancer Institute, carried out a nationwide prospective longitudinal study in which they compared cognitive difficulties among 581 breast cancer patients treated at community clinical sites across the United States with 364 age-matched healthy women. Researchers used a tool called the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Cognitive Function (FACT-Cog), which allowed women to report their own cognitive function.

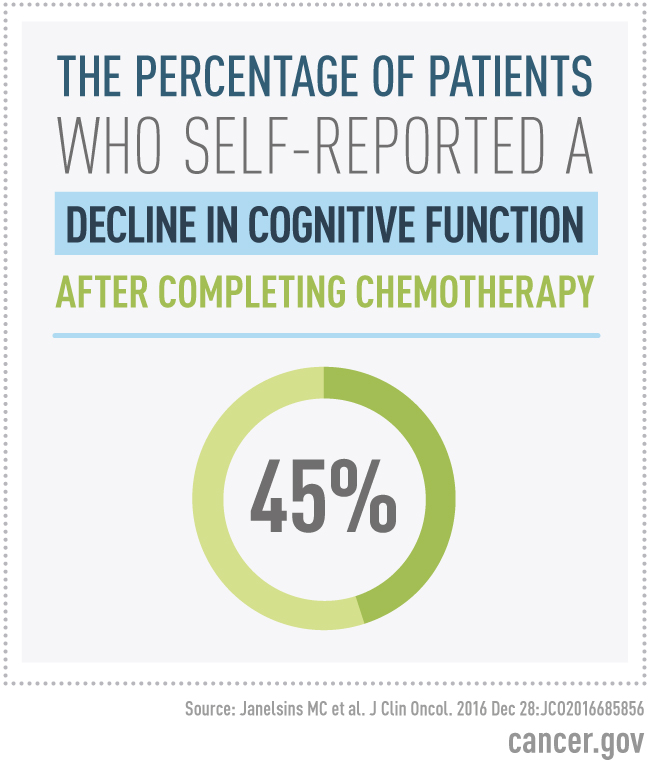

The study found that, from the time of diagnosis to after completing chemotherapy, 45.2% of patients self-reported a clinically significant decline in cognitive function, compared with 10.4% of healthy people over the same time period. And from before chemotherapy to 6 months after completing chemotherapy, 36.5% of patients reported a decline in cognitive function, compared with 13.6% of the healthy women.

In further analyses of pretreatment factors, the researchers found that both higher anxiety and higher levels of depressive symptoms before treatment were associated with lower FACT-Cog scores. This finding led the researchers to conclude that managing anxiety and depression after diagnosis and during treatment may lessen cognitive impairment and its impact on quality of life. The neuropsychological outcomes from the study have not yet been published.

Dr. Ahles, a coauthor, said this study is significant, not only because of its size, but also because it's one of the first studies of cognitive impairment in cancer patients to focus on patients seen in community-based settings. Dr. Rowland added that it's important because of the visibility it brings to the issue. "Once you start getting these reports published in journals that have a wide clinical readership, my sense is you have a greater willingness to say, 'this is a problem,'" she said.

New Directions for Research and Treatment

The need to determine who is most at risk for developing cognitive problems after cancer treatment is driving research in several different ways. Dr. Ahles has been investigating the interplay between cancer and aging. "With regard to cognition, the question becomes, 'are the changes that we're seeing due to specific effects of chemotherapy on the brain, or are they a reflection of accelerating aging on some level?'" he said. "This is a new, interesting area of research to explore."

Funding Opportunity from NCI

NCI recently released a Funding Opportunity Announcement (FOA) for research that focuses on improving the measurement and assessment of cognitive changes following cancer treatment for non-central nervous system cancers. A better understanding of acute and long-term cognitive changes can reduce uncertainty, inform care planning, and suggest possible ways to accommodate patients who experience these impairments.

NCI recently released a Funding Opportunity Announcement (FOA) for research that focuses on improving the measurement and assessment of cognitive changes following cancer treatment for non-central nervous system cancers. A better understanding of acute and long-term cognitive changes can reduce uncertainty, inform care planning, and suggest possible ways to accommodate patients who experience these impairments.

Dr. Ahles has also investigated potential genetic markers for increased vulnerability to cognitive impairment after cancer treatment, including a form (or allele) of the APOE gene called ε4, which is associated with Alzheimer's disease. Other studies have shown that breast cancer survivors who have a variant of the COMT gene, which influences how quickly the brain metabolizes dopamine, are at greater risk of cognitive impairment and that a variant of the BDNF gene can protect against chemotherapy-associated cognitive impairment.

Dr. Ahles said that, although these are all small studies, together they point to imbalances or deficits in neurotransmitter activity as risk factors for cognitive impairment after cancer treatment, a conclusion that could have a variety of treatment implications. For example, research shows that in animal models, the antidepressant fluoxetine can prevent or improve memory problems associated with the chemotherapy treatment 5-FU.

Dr. Ganz believes inflammation may be a factor in cognitive impairment after cancer treatment. In their research, she and her colleagues have found a strong association between fatigue and cognitive complaints after cancer treatment in patients with specific polymorphisms in the genes that regulate the cytokines that promote inflammation.

Finding biological risk factors like this, she noted, could be extremely helpful in devising ways to limit the cognitive effects of treatment. "If we could identify people who might be more susceptible biologically to this long-term treatment, we could test whether an intervention might be helpful," she said.

If we could identify people who might be more susceptible biologically to this long-term treatment, we could test whether an intervention might be helpful.

One recent randomized trial found that using a cognitive rehabilitation program in which cancer survivors report cognitive symptoms after chemotherapy led to lower levels of anxiety, depression, fatigue, and stress. Dr. Ganz is also planning on testing a cognitive behavioral therapy intervention, and some research has already shown this kind of therapy can be effective for cognitive problems after cancer treatment. "I think for some of the patients, it's not so much that they’re severely impaired, but they get distressed and they can't do things, so cognitive behavioral therapy might be helpful in that situation," she said.

Dr. Ganz said the latest studies are valuable because they highlight the need to listen to patients expressing these concerns. "I think the importance of [recent] research is that if patients say they have pain, they feel sad, they can’t sleep, we don't send them for complicated testing—instead, we believe what they say," she said. "So if somebody says, 'I'm really forgetful. I can't find my words very easily. I can't concentrate,' when they're telling us those things and it hasn't gotten better 6 months or a year after their treatment, they've had some kind of injury."

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario