Targeted Cancer Drug May Also Help Protect Fertility, Study Suggests

March 27, 2017, by NCI Staff

Findings from a new study in mice suggest that a class of targeted cancer drugs may have another use in some younger women being treated for cancer: preserving their fertility.

In the mouse study, researchers from the NYU Langone Medical Center and Perlmutter Cancer Center in New York showed that the targeted agents known as mTOR inhibitors block chemotherapy-induced damage to the ovaries that causes infertility.

Mice treated with mTOR inhibitors in combination with chemotherapy also had far more offspring than mice that received chemotherapy alone, the study team reported March 7 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

There are currently several options to help women of reproductive age who are undergoing ovary-damaging chemotherapy treatment maintain the possibility of having children. They include two drugs, goserelin (Zoladex®) and leuprolide (Lupron®), which temporarily shut down the ovaries to protect them during chemotherapy. The other option is oocyte (egg) or embryo cryopreservation, in which eggs are retrieved and either frozen for future fertilization or fertilized outside of the womb and frozen as embryos for future implantation.

But both options have limitations and they’re not appropriate for many girls or women, explained the study’s lead investigator, Kara Goldman, M.D., of the NYU Langone Fertility Center. A drug that helps to spare the ovaries from chemotherapy would be a welcome alternative or complement to these other options, Dr. Goldman said.

Three mTOR inhibitors are already approved for clinical use, and drugs in this class are being tested for other cancer indications, she continued, making them “uniquely positioned” to move ahead eventually into clinical trials as a fertility-preserving treatment.

Keeping the Follicles Quiet

Many chemotherapy drugs target rapidly dividing cells and damage cellular DNA, explained the study’s senior investigator, Robert Schneider, Ph.D. Cyclophosphamide, a mainstay chemotherapy treatment for breast cancer, is among the most toxic therapies to the reproductive organs, Dr. Schneider said.

Oocytes—immature egg cells—are extremely sensitive to any DNA damage, explained Teresa Woodruff, Ph.D., of Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine and director of the NIH-funded Oncofertility Consortium. Even small amounts of such damage can cause an oocyte to die.

This “hair-trigger response” to DNA damage, Dr. Woodruff continued, is a protective mechanism to ensure that an oocyte “retains its [genomic] fidelity for the next generation.”

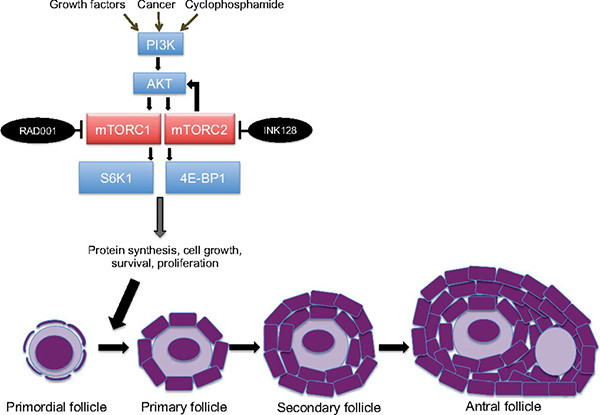

Chemotherapy also affects the primordial follicles in the ovaries, which store oocytes and are normally dormant until they become activated. Specifically, chemotherapy activates a signaling pathway in primordial follicles. The activation of this pathway causes the primordial follicles to begin maturing into primary and secondary follicles, a process that leads to the eventual release of the oocyte.

This premature maturation reduces the number of primordial follicles—and, thus, a woman’s ovarian reserve—in a phenomenon known as “follicular burnout,” Dr. Goldman explained.

Goserelin blunts the production of hormones known as gonadotropins, which are involved in controlling ovarian follicle activity, and can cause the ovaries to become temporarily dormant by protecting larger gonadotropin-sensitive follicles. In the NCI-funded POEMS trial, treatment with goserelin reduced rates of ovarian failure and improved pregnancy rates in premenopausal women being treated for breast cancer.

So, similar to the case with goserelin, researchers have sought other ways to keep primordial follicles in their dormant state during chemotherapy.

mTOR is a key component of the signaling pathway in ovarian cells that launches the transition of primordial follicles into mature follicles. mTOR’s activity is ramped up during this transition, several studies have shown, so the research team speculated that blocking mTOR could potentially prevent the transition from taking place.

Targeting mTOR is a good strategy to pursue, Dr. Woodruff said. Research in mice, for example, has shown that other drugs that target the same pathway as mTOR, including the targeted therapy imatinib (Gleevec®), can also help to protect the reserve of primordial follicles.

But more research is needed, she stressed, to “identify all of the factors and the signaling pathways that may be involved in early activation” of primordial follicles.

More Primordial Follicles, More Babies

In the study, the Langone team tested everolimus (Afinitor®)—which is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of some forms of pancreatic, kidney, and breast cancer—and sapanisertib (also known as INK128), an investigational second-generation mTOR inhibitor.

When female mice were treated with cyclophosphamide, the number of primordial follicles in their ovaries was greatly reduced and the number of maturing follicles increased. Adding an mTOR inhibitor along with chemotherapy, however, allowed the mice to retain many more primordial follicles. These mice also had much higher levels of the hormone AMH, “one of the most important measures of ovarian reserve used clinically,” the research team wrote.

Finally, when the researchers looked at the key endpoint, fertility, they found that adding an mTOR inhibitor to chemotherapy was extremely effective. Mice treated with chemotherapy alone were rendered infertile or had impaired fertility, whereas all of the mice that received both drugs became pregnant at normal rates.

In addition, mice treated with chemotherapy alone had, on average, less than half the number of pups in their litters than the mice that received both drugs.

The doses of the drugs used in the study were calculated to be roughly equivalent to what would be used in humans, Dr. Goldman said. And although there are limitations on assessing treatment-related toxicity in animal model studies, the mice that received both drugs did not exhibit any signs of side effects, they reported.

Testing Lower Doses, Planning for Trials

The researchers are actively planning their next steps, Dr. Schneider said, including designing the initial clinical trials of an mTOR inhibitor to preserve fertility in women with cancer. They’re also initiating studies in which they will collect blood samples from women being treated with everolimus to assess any effects on important fertility-related measures.

And they’re beginning the next phase of animal model studies to determine whether they can achieve the same fertility-protecting results with a lower drug dose.

“We think we can keep the dose down,” Dr. Schneider said. “We want to avoid the side effects that limit the use” of mTOR inhibitors, he said, including inflammatory sores in the mouth, called stomatitis, a common and debilitating side effect of these drugs.

The approach used in this study holds promise, Dr. Woodruff said. But she cautioned that there’s still much to do before mTOR inhibitors can transition to the clinic as a fertility-preserving treatment. That includes assessing how the drugs affect the overall efficacy of cancer treatment and whether the surviving oocytes are free of genetic mutations that might be passed on to offspring.

Overall, she continued, protecting fertility in people being treated for cancer will not be a one-size-fits-all solution. And with the availability of new targeted therapies and increasing use of combinations of therapies, developing and testing fertility-preserving therapies will be challenging.

Cancer therapies “work in different ways, not only in cancer cells but also in oocytes,” Dr. Woodruff said. “So the more we understand how oocytes are activated and damaged by these therapies, the more we’ll be able to match them with a tailored protective therapy.”

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario