06/06/2017 09:00 AM EDT

Skin is the largest organ in the human body, yet we often take for granted all of the wonderful things that it does to keep us healthy. That’s not the case for people who suffer from a group of rare, scale-forming skin disorders known as ichthyoses, which are named after “ichthys,” the Greek word for […]

Skin Health: New Insights from a Rare Disease

Skin is the largest organ in the human body, yet we often take for granted all of the wonderful things that it does to keep us healthy. That’s not the case for people who suffer from a group of rare, scale-forming skin disorders known as ichthyoses, which are named after “ichthys,” the Greek word for fish.

Each year, more than 16,000 babies around the world are born with ichthyoses [1], and researchers have identified so far more than 50 gene mutations responsible for various types and subtypes of the disease. Now, an NIH-funded research team has found yet another genetic cause—and this one has important implications for treatment. The new discovery implicates misspellings in a gene that codes for an enzyme playing a critical role in building ceramide—fatty molecules that help keep the skin moist. Without healthy ceramide, the skin develops dry, scale-like plaques that can leave people vulnerable to infections and other health problems.

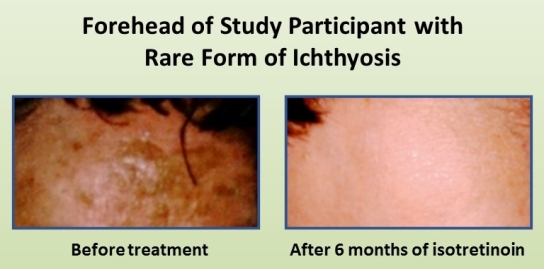

Two patients with this newly characterized form of ichthyosis were treated with isotretinoin (Accutane), a common prescription acne medication, and found that their symptoms resolved almost entirely. Together, the findings suggest that isotretinoin works not only by encouraging the rapid turnover of skin cells but also by spurring patients’ skin to boost ceramide production, albeit through a different biological pathway.

Keith Choate at Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, has dedicated his career to studying ichthyoses. That includes working with his team to recruit more than 800 affected families into the National Registry for Ichthyosis and Related Skin Disorders, now housed at Yale.

In the study just reported in The American Journal of Human Genetics, his team screened 750 affected individuals in the registry to learn whether they carried any one of the mutations previously known to cause these skin disorders [2]. They were especially interested in identifying people who didn’t have any of those mutations. That’s because they realized those unexplained cases of ichthyosis might be the key to discovering additional genes with important roles in healthy and diseased skin.

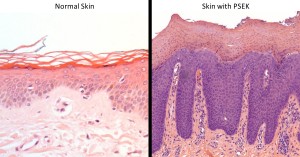

Caption: People with PSEK have a thickended outer layer of skin, known as the stratum corneum. in which nuclei of the cells (purple) are abnormally retained.

Source: Keith Choate, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT

Source: Keith Choate, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT

Their initial screen identified four patients with a recessive form of ichthyosis known as progressive symmetric erythrokeratoderma (PSEK) who tested negative for all known disease mutations. PSEK is an extremely rare type of ichthyosis, featuring areas of red, scaly, thickened skin that are symmetrically distributed on the body. Those affected areas often expand and worsen over time.

In search of a genetic cause for their condition, the researchers sequenced the exome from each patient—the exome is the part of the genome that codes for proteins, representing only about 1.5% of the DNA. Those exome sequences turned up several mutations in the gene encoding the KDSR enzyme in all four people. That was intriguing because the KDSR enzyme plays an essential role in the multi-step process through which the skin builds ceramide.

Interestingly, two of the individuals with KDSR mutations only seemed to carry one deleterious gene copy. That was puzzling because the researchers knew the condition was recessive, requiring two malfunctioning copies of the gene to cause the disease. Choate’s team suspected that the second apparently “good” copy of KDSR must include a mutation that couldn’t be detected in the exome sequences.

To look deeper, they fully sequenced the entire genome of one of the two people. Indeed, the complete DNA sequence data showed that the copy of KDSR that had appeared “good” was actually flipped around in the genome in the wrong direction, disrupting its function. Further study of the patients’ skin tissue confirmed that the KDSR gene was indeed malfunctioning, leading to problems in the production of protective ceramide.

The new genetic evidence helps to explain why isotretinoin has worked surprisingly well in treating this form of ichthyosis. Ceramide is produced in one of three ways. Our skin produces ceramide “from scratch” by building the lipids from smaller building blocks. It’s this pathway that breaks down in patients with PSEK.

But skin cells can also produce ceramide by breaking down cell membranes to release components that can be converted to the lipid via one of two related biochemical pathways. The new findings suggest that isotretinoin treatment allows skin cells to compensate for their genetic defect by encouraging them to produce ceramide via these alternative means.

The findings come as an encouraging sign of progress for people with ichthyoses. For the rest of us, they also highlight the importance of ceramide, which is found as an active ingredient in many moisturizers, for maintaining general skin health.

References:

[1] What is ichthyosis? Foundation for Ichthyosis & Related Skin Types.

[2] Mutations in KDSR cause recessive progressive symmetric erythrokeratoderma. Boyden LM, Vincent NG, Zhou J, Hu R, Craiglow BG, Bayliss SJ, Rosman IS, Lucky AW, Diaz LA, Goldsmith LA, Paller AS, Lifton RP, Baserga SJ, Choate KA. Am J Hum Genet. 2017 Jun 1;100(6):978-984.

Links:

Ichthyosis Overview (National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases/NIH)

Foundation for Ichthyosis & Related Skin Types (Colmar, PA)

Keith Choate (Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT)

NIH Support: National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Human Genome Research Institute

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario