12/13/2016

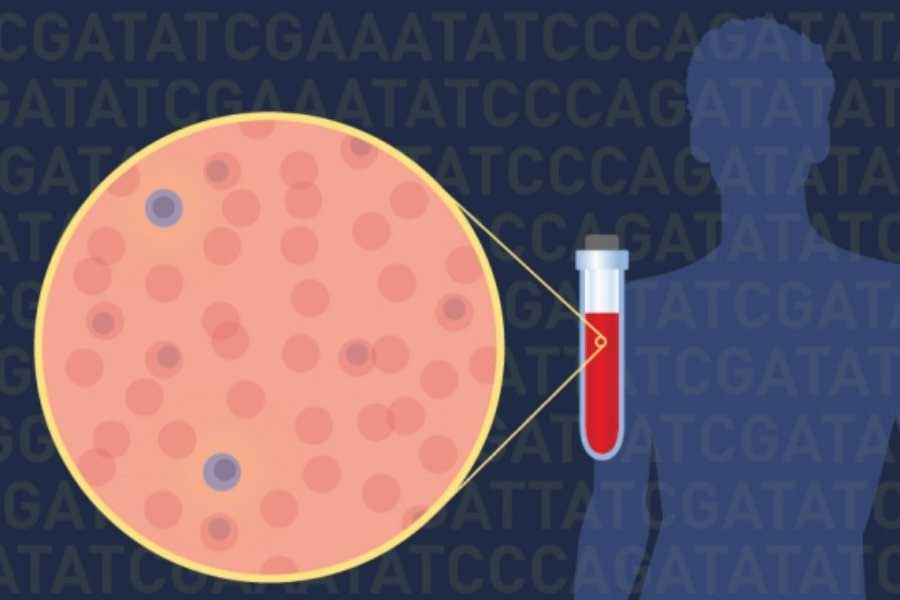

Individual tumor cells circulating in the blood of patients with multiple myeloma may be a new source of information about the genetic changes driving the disease, according to the results of a pilot study. In the study, researchers isolated individual tumor cells from the blood of patients with multiple myeloma. They then analyzed these cells and found that they provided as much, if not more, information about the genetic changes associated with multiple myeloma as cells collected from the bone marrow.

Single Tumor Cells Reveal Clues to Biology of Multiple Myeloma

December 13, 2016 by NCI Staff

Individual tumor cells circulating in the blood of patients with multiple myeloma may be a new source of information about the genetic changes driving the disease, according to the results of a pilot study.

In the study, researchers isolated individual tumor cells from the blood of patients with multiple myeloma. They then analyzed these cells and found that they provided as much, if not more, information about the genetic changes associated with multiple myeloma as cells collected from the bone marrow.

The single-cell approach, which only requires a blood draw, is less invasive and painful for patients than a bone marrow biopsy. The new study also suggests that it may provide more genetic information about a patient’s cancer, the research team wrote in the November 2 Science Translational Medicine.

“This study demonstrates that we can get extraordinarily detailed genetic information from circulating tumor cells even if these cells occur at low frequencies [in the blood],” said study coauthor Jens Lohr, M.D., Ph.D., of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard. His team estimates that the approach can detect one myeloma cell in a million cells.

When Treatments Fail

The treatment options for patients with multiple myeloma have increased in recent years, with a number of new approvals from the Food and Drug Administration. In most patients with this disease, however, treatments eventually stop working.

A goal of the study was to develop a tool that allows doctors to detect and monitor genetic changes in the disease at any given point in time, including at relapse, noted Dr. Lohr, who treats patients at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

“Drug resistance is one of the most important phenomena to understand in multiple myeloma,” said Dr. Lohr. “We could use the new [single-cell] approach to follow patients who are prone to developing drug resistance to better understand why the resistance occurred. Our approach can be used to characterize drug-resistant multiple myeloma cells either in the blood or in the bone marrow, even if there are very few of them.”

There’s been growing interest among researchers in trying to analyze single cancer cells, including circulating tumor cells, in multiple myeloma and many other cancers, noted Kevin Howcroft, Ph.D., of NCI’s Division of Cancer Biology, who was not involved in the research.

“But we have not known how many tumor cells are circulating in blood and whether these cells could be interrogated to learn how a tumor is behaving,” Dr. Howcroft continued.

Testing the Approach

The new study provides some answers. Dr. Lohr and his colleagues began by isolating at least 12 single circulating multiple myeloma tumor cells from each of 24 patients. Their approach uses biological markers to help sort and concentrate plasma cells, the cells in which this cancer arises, within a sample; individual myeloma tumor cells are then isolated manually under a microscope.

Next, the researchers analyzed DNA from the individual cells for 35 regions of the human genome that may be mutated in multiple myeloma. They found the same DNA mutations in the individual cells as were identified in bone marrow tissue samples collected from the same patients.

For some patients, the single-cell approach revealed cancer-related genetic changes that were not detected in the bone marrow samples. This may have been because the bone marrow biopsy did not produce sufficient DNA for analysis or because not enough myeloma cells in the biopsy sample contain the mutation, the study authors noted.

“The fact that we found genetic changes in peripheral blood that were not detectable in bone marrow suggests that we might be missing information if we only rely on bone marrow biopsies, which are typically obtained from a single site,” said Dr. Lohr.

To learn more about the tumor cells, the researchers sequenced RNA from the single multiple myeloma cells. The findings from these analyses allowed the investigators to distinguish multiple myeloma cells from healthy plasma cells and also to identify subsets of multiple myeloma cells within a sample.

“You can get information about the landscape of genetic changes in cells from DNA and RNA sequencing,” said Dr. Howcroft. Studying gene expression can also reveal the presence of certain chromosomal abnormalities that may play a role in multiple myeloma, the study authors noted.

Precursor Conditions

The single-cell approach also potentially could help researchers learn more about the precursor states that may lead to multiple myeloma, Dr. Lohr said, such as monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance, or MGUS. About 1% of individuals with MGUS progress to cancer each year.

“Doctors do not routinely subject individuals with MGUS to bone marrow biopsies because these patients don’t have disease,” said Dr. Lohr.

Currently, there’s no way to identify which people with MGUS are likely to eventually develop multiple myeloma. The current study included a patient with MGUS, and the single-cell approach revealed that the patient had a cancer-causing mutation in an oncogene known as NRAS.

The finding raises important questions, noted Dr. Lohr. “Will this patient develop cancer soon? If he has an oncogene mutation but doesn’t develop cancer, why not?”

Researchers could potentially use the single-cell approach to follow patients with MGUS over time to identify potential biological markers associated with progression to multiple myeloma, Dr. Lohr added.

Looking Ahead

The study authors cautioned that the current work was a feasibility study and that more research is needed.

“We have to see if the analysis of single cells can influence clinical decision making,” said Dr. Lohr. “And we have to figure out if the information gleaned from single cells can help us understand the mechanisms of resistance.”

Nonetheless, Dr. Howcroft predicted that the single-cell approach would lead to insights into the biology of multiple myeloma. “It might help us figure out what we don’t know that we don’t know,” he said. “And that’s always exciting.”

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario