|

| MMWR Weekly Vol. 65, No. 39 October 07, 2016 |

| PDF of this issue |

State-Specific Prevalence of Current Cigarette Smoking and Smokeless Tobacco Use Among Adults — United States, 2014

Weekly / October 7, 2016 / 65(39);1045–1051

Kimberly H. Nguyen, MS1; LaTisha Marshall, DrPH1; Susan Brown, MPH1; Linda Neff, PhD1 (View author affiliations)

View suggested citationSummary

What is already known about this topic?Tobacco use is the leading cause of preventable disease and death in the United States. In recent years, cigarette smoking prevalence has declined in many states; however, there has been little change in the prevalence of current smokeless tobacco use or concurrent use of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco in most states, with prevalence increasing in some states.

What is added by this report?State-specific differences and disparities in any cigarette/smokeless tobacco use exist between sexes and among racial/ethnic groups. The highest prevalence of any cigarette and/or smokeless tobacco use in the United States was seen in West Virginia. The difference in prevalence of any cigarette and/or smokeless tobacco use across states spanned almost 21 percentage points, ranging from 11.3% in Utah to 32.2% in West Virginia. Any cigarette and/or smokeless tobacco use was higher among males than females in all 50 states. Non-Hispanic whites had the highest prevalence of cigarette smoking and/or smokeless tobacco use in eight states, followed by non-Hispanic persons of other races in six states, non-Hispanic blacks in five states, and Hispanics in two states.

What are the implications for public health practice?The significantly higher prevalence of tobacco use among males and some racial/ethnic groups in several states underscores the importance of implementing comprehensive tobacco control and prevention interventions to reduce tobacco use and tobacco-related disparities across states, including increasing tobacco product prices, implementing and enforcing comprehensive smoke-free laws, warning about the dangers of tobacco use through mass media campaigns. Increasing access to evidence-based behavioral counseling and FDA-approved medication can also help reduce tobacco use, particularly in populations with high use prevalence.

Kimberly H. Nguyen, MS1; LaTisha Marshall, DrPH1; Susan Brown, MPH1; Linda Neff, PhD1 (View author affiliations)

View suggested citationTobacco use is the leading cause of preventable disease and death in the United States, resulting in approximately 480,000 premature deaths and more than $300 billion in direct health care expenditures and productivity losses each year (1). In recent years, cigarette smoking prevalence has declined in many states; however, there has been relatively little change in the prevalence of current smokeless tobacco use or concurrent use of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco in most states, and in some states prevalence has increased (2). CDC analyzed data from the 2014 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) to assess state-specific prevalence estimates of current use of cigarettes, smokeless tobacco, and cigarette and/or smokeless tobacco (any cigarette/smokeless tobacco use) among U.S. adults. Current cigarette smoking ranged from 9.7% (Utah) to 26.7% (West Virginia); current smokeless tobacco use ranged from 1.4% (Hawaii) to 8.8% (Wyoming); current use of any cigarette and/or smokeless tobacco product ranged from 11.3% (Utah) to 32.2% (West Virginia). Disparities in tobacco use by sex and race/ethnicity were observed; any cigarette and/or smokeless tobacco use was higher among males than females in all 50 states. By race/ethnicity, non-Hispanic whites had the highest prevalence of any cigarette and/or smokeless tobacco use in eight states, followed by non-Hispanic other races in six states, non-Hispanic blacks in five states, and Hispanics in two states (p<0.05); the remaining states did not differ significantly by race/ethnicity. Evidence-based interventions, such as increasing tobacco prices, implementing comprehensive smoke-free policies, conducting mass media anti-tobacco use campaigns, and promoting accessible smoking cessation assistance, are important to reduce tobacco use and tobacco-related disease and death among U.S. adults, particularly among subpopulations with the highest use prevalence (3).

The BRFSS is an annual state-based telephone (landline and cell phone) survey of noninstitutionalized U.S. adults aged ≥18 years.* During 2014, the median survey response rate for all states, territories, and the District of Columbia (DC) was 47.0% (range = 25.1%–60.1%) (4). Current cigarette smokers were persons who reported smoking at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and smoked “every day” or “some days” at the time of the survey. Current smokeless tobacco users are persons who reported using chewing tobacco or snus “every day” or “some days” at the time of the survey. Current any cigarette and/or smokeless tobacco users were persons who reported current use of cigarettes and/or smokeless tobacco products.

Prevalence estimates with 95% confidence intervals for cigarette smoking, smokeless tobacco use, and any cigarette and/or smokeless tobacco use were calculated overall and by state and sex. Because of limited sample size, data were stratified by race/ethnicity for current any cigarette and/or smokeless tobacco use, but not for current cigarette use or smokeless tobacco use. Race/ethnicity groups were categorized as non-Hispanic white (white), non-Hispanic black (black), Hispanic, and non-Hispanic other (Asian, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaska Native, or some other group). Data were weighted to adjust for nonresponse and to yield state representative estimates. Chi-square tests were conducted to assess differences among groups, with p<0.05 considered to be statistically significant.

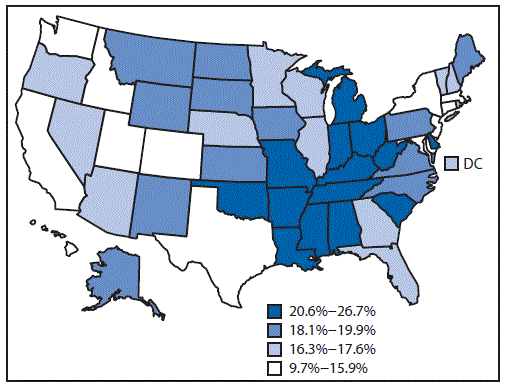

By state, overall cigarette smoking prevalence ranged from 9.7% (Utah) to 26.7% (West Virginia) (Table 1)(Figure). Prevalence of smokeless tobacco use ranged from 1.4% (Hawaii) to 8.8% (Wyoming). Prevalence of any cigarette and/or smokeless tobacco use ranged from 11.3% (Utah) to 32.2% (West Virginia).

Cigarette smoking was significantly higher among males than females in 34 states (Table 2). Among males, cigarette smoking ranged from 11.2% (Utah) to 27.8% (West Virginia), and among females, from 8.2% (Utah) to 25.6% (West Virginia). Smokeless tobacco use was significantly higher among males than females in 44 states for which statistically stable estimates could be computed, and among males, ranged from 2.3% (Hawaii) to 16.5% (West Virginia). Use among females ranged from 0.40% (Maryland) to 3.4% (Mississippi). Any cigarette and/or smokeless tobacco use was significantly higher among males than among females in all 50 states, and ranged from 14.1% (Utah) to 39.2% (West Virginia) among males, and 8.5% (Utah) to 25.5% (West Virginia) among females.

Any cigarette and/or smokeless tobacco use ranged from 7.5% (DC) to 32.4% (West Virginia) among whites; 14.6% (Texas) to 36.1% (Vermont) among blacks; 8.0% (Maryland) to 45.5% (North Dakota) among Hispanics; and 9.6% (Maryland) to 45.5% (North Dakota) among adults of non-Hispanic other races (Table 3). The prevalence of any cigarette and/or smokeless tobacco use differed significantly by race/ethnicity in 21 states. Prevalence was highest among whites in eight states (Arizona, Delaware, Georgia, Maryland, New York, North Carolina, Texas, and Virginia), followed by adults of non-Hispanic other races in six states (Arkansas, Florida, Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and South Carolina), blacks in five states (California, Illinois, Indiana, New Jersey, and Wisconsin), and Hispanics in two states (Connecticut and Michigan).

Discussion

The overall prevalence of current cigarette smoking declined significantly in approximately half of U.S. states during 2011–2013 (1); however, differences in any cigarette and/or smokeless tobacco use exist between sexes and among racial/ethnic groups and states. The highest prevalence of cigarette and/or smokeless tobacco use in the United States was seen in West Virginia. Furthermore, males and whites had higher prevalences of any cigarette and/or smokeless tobacco use than females and other race/ethnicities. The difference in prevalence of any cigarette and/or smokeless tobacco use across states spanned almost 21 percentage points, ranging from 11.3% in Utah to 32.2% in West Virginia. The use of any cigarette and/or smokeless tobacco was particularly high among men compared with women. These disparities might be partly explained by sociocultural influences and norms related to the acceptability of tobacco use (4,5), as well as variations in the implementation of evidence-based tobacco prevention and control measures (6). Continued implementation of proven population-based interventions, including increasing tobacco product prices, implementing and enforcing comprehensive smoke-free laws, warning about the dangers of tobacco use through mass media campaigns, and increasing access to evidence-based clinical interventions (including behavioral counseling and FDA-approved medication), can help reduce tobacco use, particularly in populations with the highest use prevalence (3).

These findings highlight the importance of enhanced implementation of evidence-based strategies to help smokers and other tobacco users quit completely. Public Health Service guidelines recommend using both medication and counseling to help cigarette smokers quit.† In addition, state tobacco control programs are critical to promoting health system changes that can facilitate the screening and treatment of tobacco use within clinical settings; expanding insurance coverage and use of proven cessation treatments, and increasing use of state quit lines (telephone-based tobacco cessation services) also help tobacco users quit (3). Cessation programs involving both medication and counseling, in combination with comprehensive tobacco control measures, as recommended by the World Health Organization§ and CDC's best practices for comprehensive tobacco control programs (3), can help to reduce tobacco-related morbidity and mortality.

The findings in this report are subject to at least three limitations. First, BRFSS does not include adults without either wireless or landline telephone service; however, their exclusion would not be expected to introduce any major bias because only 3.1% of U.S. adults reported having no telephone service in 2015. ¶ Second, these data are self-reported and might be subject to reporting bias. Although self-reported smoking yields lower prevalence estimates than assessment with serum cotinine, a metabolite of nicotine, it is unlikely that underreporting will have a large effect on the findings of this report because of the overall high concordance between self-reported smoking and biochemical assessment with cotinine (7). Finally, the median state response rates ranged from 25.1% to 60.1%. Even after adjusting for nonresponse, low response rates can increase the potential for bias if there are systematic differences between respondents and nonrespondents; however, BRFSS has been shown to be valid and reliable (8).

There remains considerable variability in current use of cigarettes, smokeless tobacco, and any cigarette and/or smokeless tobacco use across states and by sex and race/ethnicity. The significantly higher prevalence among males and certain racial/ethnic groups in several states underscores the importance of implementing comprehensive tobacco control and prevention interventions to reduce tobacco use and tobacco-related health disparities (9). However, during fiscal year 2016, despite combined revenue of $25.8 billion from settlement payments and tobacco taxes for all states, states will spend only $468 million (1.8%) on comprehensive tobacco control programs, representing <15% of the CDC-recommended level of funding for all states combined (10). Comprehensive tobacco control programs funded at CDC-recommended levels have been shown to effectively reduce tobacco use; thus, enhanced and equitable adoption of evidence-based measures across all states could be beneficial to decrease the prevalence of tobacco use across all population groups in the United States (3).

Acknowledgments

Brian King, Ralph S. Caraballo, Ahmed Jamal, Erin O’Connor, Office on Smoking and Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC.

Corresponding author: Kimberly Nguyen, uxp1@cdc.gov, 770-488-5572.

1Office on Smoking and Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC, Atlanta, GA.

References

- CDC. 2014 surgeon general’s report: the health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2014.http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/50th-anniversary/index.htm

- Nguyen K, Marshall L, Hu S, Neff L. State-specific prevalence of current cigarette smoking and smokeless tobacco use among adults aged ≥18 years—United States, 2011–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:532–6. PubMed

- CDC. Best practices for comprehensive tobacco control programs—2014. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2014.http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/stateandcommunity/best_practices/pdfs/2014/comprehensive.pdf

- Delnevo CD, Wackowski OA, Giovenco DP, Manderski MT, Hrywna M, Ling PM. Examining market trends in the United States smokeless tobacco use: 2005–2011. Tob Control 2014;23:107–12. . CrossRef PubMed

- Siahpush M, McNeill A, Hammond D, Fong GT. Socioeconomic and country variations in knowledge of health risks of tobacco smoking and toxic constituents of smoke: results from the 2002 International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control 2006;15(Suppl 3):iii65–70. . CrossRef PubMed

- CDC. State tobacco activities tracking and evaluation (STATE) system. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2014. https://www.cdc.gov/statesystem/

- Connor Gorber S, Schofield-Hurwitz S, Hardt J, Levasseur G, Tremblay M. The accuracy of self-reported smoking: a systematic review of the relationship between self-reported and cotinine-assessed smoking status. Nicotine Tob Res 2009;11:12–24. . CrossRef PubMed

- Nelson DE, Holtzman D, Bolen J, Stanwyck CA, Mack KA. Reliability and validity of measures from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). Soz Praventivmed 2001;46(Suppl 1):S3–42. PubMed

- CDC. Best practices user guide: health equity. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2015. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/stateandcommunity/best-practices-health-equity/index.htm

- Tobaccofreekids.org Broken promises to our children. A state-by-state look at the 1998 state tobacco settlement 17 years later; Princeton, NJ: Tobaccofreekids.org; 2015,http://www.tobaccofreekids.org/microsites/statereport2016/

* Additional information available at http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/.

† Additional information available at http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/tobacco/treating_tobacco_use08.pdf.

§ Additional information available at http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241563918_eng_full.pdf.

¶ Additional information available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/wireless201605.pdf.

.jpg)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario