10/21/2016

An immunotherapy approach that uses a new method of preparing immune cells may provide a potential treatment option for some patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), results from an early-stage clinical trial suggest. In the phase I trial, researchers collected the immune cells, called natural killer (NK) cells, from donors, manipulated them to be better cancer killers, and infused the cells into patients with AML who had previously exhausted all other treatment options. The approach—which uses a new method of manipulating NK cells that is different from those used in prior studies—led to partial or complete remissions in five out of the nine patients who could be evaluated. It also appeared to be safe, with patients experiencing only minor side effects.

Modified Immunotherapy Approach Shows Promise for Leukemia

October 21, 2016 by NCI Staff

An immunotherapy approach that uses a new method of preparing immune cells may provide a potential treatment option for some patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), results from an early-stage clinical trial suggest.

In the phase I trial, researchers collected the immune cells, called natural killer (NK) cells, from donors, manipulated them to be better cancer killers, and infused the cells into patients with AML who had previously exhausted all other treatment options. The approach—which uses a new method of manipulating NK cells that is different from those used in prior studies—led to partial or complete remissions in five out of the nine patients who could be evaluated. It also appeared to be safe, with patients experiencing only minor side effects.

Results from the new study, led by Todd Fehniger, M.D., Ph.D., of the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, were published September 21 in Science Translational Medicine.

The new method for manipulating NK cells “holds promise, and is just a start,” said Mattias Carlsten, M.D., Ph.D., who studies NK-cell immunotherapy at Karolinska Institutet in Sweden, but who was not involved in the study.

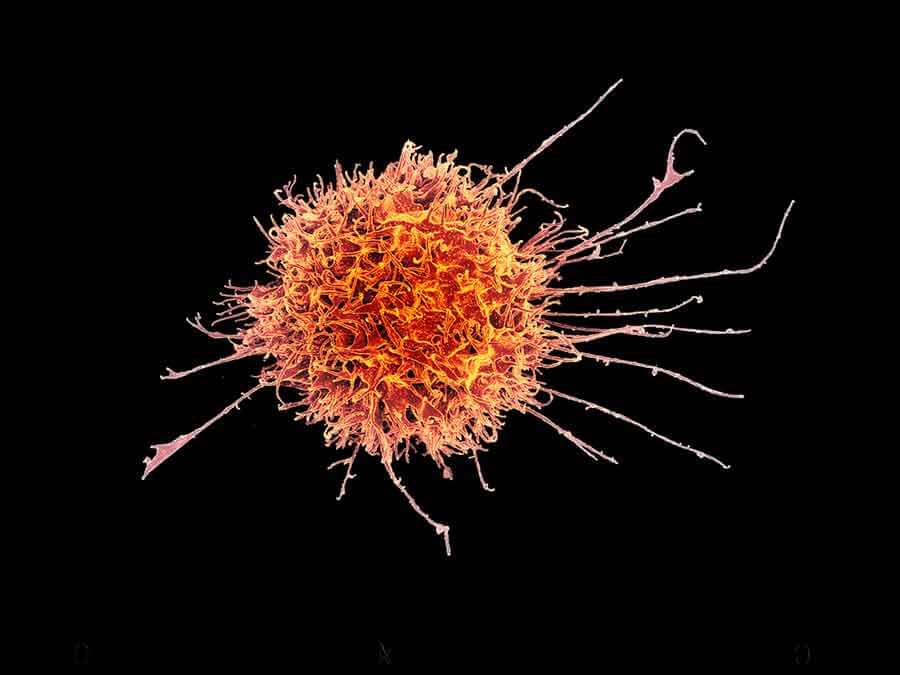

Natural Cancer Killers

NK cells are the body’s first line of defense against harmful cells, such as foreign, virus-infected, and cancer cells. NK cells must first be turned on, or activated, by a variety of molecular signals emitted by the target cells before they can release toxic molecules to kill the targets.

For nearly a decade, researchers have been developing immunotherapy approaches that take advantage of the cancer-killing power of NK cells. However, previous NK cell-based therapies have had limited effects on tumors, likely because the NK cells had low activity and did not survive for very long in patients, the study authors explained.

But in 2009, researchers at Washington University found that, when exposed to a specific mixture of signaling molecules called cytokines, mouse NK cells became activated, multiplied, and killed target cells better than untreated NK cells—even if the activated NK cells did not encounter the target cells until weeks or months after cytokine exposure.

Because these activated NK cells seemed to “remember” their targets, they were dubbed memory-like NK cells. Dr. Fehniger’s group later showed that the same cytokine mixture could also induce a memory-like state in human NK cells. Their trial is the first to test the ability of memory-like NK cells to recognize and eliminate AML in patients.

Encouraging Results

Only about 60% of younger patients and 30%-40% of older patients with AML, one of the most common blood cancers in adults, respond to standard therapy. Of those patients that do respond, the cancer is likely to return. And although bone marrow transplants can be effective for some patients with AML, not all patients are able to endure the procedure.

Thus, “there is a huge unmet need” to find therapies that are effective for patients whose AML never initially responded, or has stopped responding to standard therapy, said Rizwan Romee, M.D., co-first author of the study.

AML represents a good opportunity for implementing NK-based treatments because earlier studies have shown that “NK cells have some special, unexplained activity in patients with AML,” said Jeffrey Miller, M.D., of the University of Minnesota, who was not involved in the study.

In preclinical studies that led to the trial, the research team tested the ability of human memory-like NK cells to kill leukemia cells in culture. They isolated NK cells from the blood of human donors, and either made them memory-like by exposing them to the cytokine mixture or left them untreated as a control. Compared with control NK cells, memory-like NK cells produced greater amounts of toxic molecules and killed more leukemia cells.

Next, the researchers transferred memory-like or control NK cells into mice bearing human leukemia, and observed that the memory-like NK cells reduced leukemia burden to a greater extent than control cells and extended survival.

These results gave the team the confidence to initiate a small phase I clinical trial to test the safety of this therapeutic approach in humans.

For each of the 13 patients with AML enrolled in the trial, the researchers obtained NK cells from a close relative. Using a relative’s cells increases the likelihood that the NK cells will recognize and attack the leukemia cells while sparing healthy cells, and it reduces the chances that the infused NK cells will be rejected by the patient’s immune system, Dr. Romee explained.

The researchers then activated the relative’s NK cells by exposing them to the cytokine mixture overnight in the laboratory. After undergoing chemotherapy treatment to wipe out their existing immune cells, each patient received an infusion of one of three different doses of memory-like NK cells.

Eight days later, the researchers isolated NK cells from the patients’ blood and found that compared with the patient’s own NK cells—distinguished by different “self” markers—more of the donated memory-like cells produced killing molecules. The memory-like cells were also actively growing in the patients. Both findings, the researchers wrote, suggested that the memory-like NK cells were functioning well in patients.

At one month after the infusion, four of the patients had complete remissions and one had a partial remission. Four patients did not respond, and responses could not be evaluated in the remaining four patients—three died of bacterial infections, a common occurrence for patients with AML, and another was unable to receive a full dosage of the therapy. For each of the three doses of NK cells tested, at least one patient had a complete remission.

Initially, there were concerns that patients could become sick from high levels of the toxic molecules produced by activated NK cells, or that the donor’s NK cells could attack healthy cells in the patient’s body—a phenomenon known as graft-versus-host disease. But, overall, the treatment appeared to be safe.

“None of our patients had graft-vs-host disease or any symptoms suggestive of toxicity, such as high-grade fever or large fluctuations in blood pressure,” said Dr. Romee.

Future Studies

The fact that about half of the nine evaluable patients in the trial responded to the treatment is “very encouraging,” Dr. Romee said, “because these were extremely high-risk patients whose cancer continued to grow despite multiple rounds of chemotherapy.”

But because it was a small trial with a short follow-up time, the team will soon start an expanded clinical trial to test the memory-like NK therapy in a larger number of patients with AML, he continued.

Determining the best approach to preparing NK cells and the most effective protocol for treatment delivery also warrant further investigation, said Dr. Carlsten, who is collaborating with researchers at the National Institutes of Health on NK cell-based studies.

Currently, researchers are using several different methods to “prime” NK cells used for cancer therapy, such as activating them with different cytokines or adding a step in which they are expanded in the lab. Dr. Miller’s group is exploring the use of virus exposure to generate memory-like NK cells.

While it is clear that NK-cell therapies should be further pursued, he said, “future studies will need to determine what the optimal manipulation of NK cells is.”

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario