Volume 26, Number 4—April 2020

Research Letter

Brucella melitensis in Asian Badgers, Northwestern China

On This Page

Figures

Article Metrics

Xiafei Liu1, Meihua Yang1, Shengnan Song1, Gang Liu, Shanshan Zhao, Guangyuan Liu, Sándor Hornok, Yuanzhi Wang, and Hai Jiang

Abstract

We isolated Brucella melitensis biovar 3 from the spleen of an Asian badger (Meles leucurus) in Nilka County, northwestern China. Our investigation showed that this isolate had a common multilocus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis 16 genotype, similar to bacterial isolates from local aborted sheep fetuses.

Brucellosis can be transmitted between domestic animals and wildlife (1). Brucella melitensis has been isolated from wildlife, such as chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra) (2), Alpine ibex (Capra ibex) (3), and Iberian wild goat (Capra pyrenaica) (4). Badgers are major predators in forests and consume a broad spectrum of food items, including small terrestrial vertebrates and their cadavers (5), which might result in contact with pathogens from tissues of these vertebrates. We report an Asian badger (Meles leucurus) in China naturally infected with B. melitensis biotype 3.

This study was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Shihezi University (approval no. AECSU2017–04). In 2017, a total of 7 illegally hunted and dying badgers in Nilka County, northwestern China, were confiscated by the local government.

We identified the animals as Asian badgers by using a PCR targeting the 16S rDNA gene (GenBank accession no. MH155253). We collected different organs or tissues, including heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, small intestine, large intestine, and blood, from all badgers. We separated serum from blood samples by centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 15 min and tested serum by using the rose bengal test (RBT) and serum agglutination test (SAT) (6). To detect Brucella antigens, we used immunohistochemical staining of liver and spleen tissue sections by pipetting mouse anti–Brucella melitensis IgG diluted 1:100 in 30% bovine serum albumin/phosphate-buffered saline onto each section. For comparison, we collected samples from 14 aborted sheep fetuses from Nilka County.

We extracted genomic DNA from all samples by using a commercial kit (Blood and Cell and Tissue Kit; BioTeke, ). We used the partial omp22 gene (238 bp) encoding 22-kD outer membrane protein to identify the Brucella genus and the IS711 gene to identify Brucella species. We used PCRs that have been described (7). We used Brucella reference strains (B. melitensis 16M and B. abortus 2308) as positive controls and double-distilled water as a negative control.

We homogenized spleen samples of badgers and the 14 aborted sheep fetuses and inoculated these homogenates onto individual Brucella agar plates, which we then incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 for 5 days. We tested putative Brucella colonies by using H2S production, dye inhibition, agglutination by monospecific serum, and sensitivity to bacteriophages (Appendix Table). We analyzed colonies by using a multilocus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis (MLVA) typing assay (8).

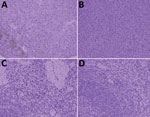

Only serum from badger no. 2 was positive for smooth Brucella antigen by RBT and SAT; the specific antibody titer was 1:160 (≈125 IU/mL). We successfully amplified 2 genetic markers (regions of the omp22 and IS711 genes) from blood, heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, small intestine, and large intestine from badger no. 2 but not from samples of other badgers. In addition, we isolated B. melitensis biotype 3 from badger no. 2 and 5 aborted sheep fetuses according to phenotypic identification (Appendix Table). MLVA-16 typing indicated that the isolates from badger no. 2 and aborted sheep fetuses had a common MLVA-16 type (1-5-3-13-2-2-3-2-4-40-8-8-4-3-7-7). In addition, immunohistochemical staining with a brown chromogen (diaminobenzidine) identified Brucella antigens in liver and spleen of badger no. 2 (Figure).

B. melitensis is isolated mainly from goats and sheep, in which it causes fetal abortion (1). The Asian badger is a semihibernating, burrowing animal species that has not been reported to harbor this pathogen. In a previous study, Li and Hu reported that 0.30% (12/4,015) of sheep in Nilka County, China, were serologically positive for smooth Brucella antigen by RBT and 9.75% (145/1,485) were serologically positive for smooth Brucella antigen by SAT (9). The habitats of Asian badgers and the grazing areas of sheep and goats partially overlap, which can be most likely explained by observations of shepherds that Asian badgers eat aborted fetuses or their placentas during lambing season in winter. In this study, B. melitensis biovar 3 isolates, designated as XJ1802 and XJ1804 strains, were found in aborted sheep fetuses and an Asian badger. MLVA-16 typing indicated that they shared a common MLVA-16 type (Appendix Figure). This finding suggests that the Asian badger is a Brucella spillover host that becomes infected from sheep that act as a reservoir host.

Another study reported that coyotes were infected probably through ingestion of aborted fetuses and placentas in enzootic brucellosis areas (10). In our study, we detected Brucella DNA from blood, heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, small intestine, and large bowel of badger no. 2 and identified B. melitensis biovar 3 from spleen tissue. This finding suggests that pathologic changes in multiple organs or tissues caused by B. melitensis might occur.

In the future, it will be essential to evaluate the clinical status of Asian badgers naturally infected with B. melitensis. In addition, more extensive surveillance is necessary to expand our knowledge on the epidemiologic interface between wildlife and domestic animals in the context of Brucella infections.

Dr. Xiafei Liu is a graduate student at the School of Medicine, Shihezi University, Shihezi, China. Her primary research interest is emerging infectious diseases.

References

- Godfroid J. Brucellosis in wildlife. Rev Sci Tech. 2002;21:277–86.

- Garin-Bastuji B, Oudar J, Richard Y, Gastellu J. Isolation of Brucella melitensis biovar 3 from a chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra) in the southern French Alps. J Wildl Dis. 1990;26:116–8.

- Ferroglio E, Tolari F, Bollo E, Bassano B. Isolation of Brucella melitensis from alpine ibex. J Wildl Dis. 1998;34:400–2.

- Muñoz PM, Boadella M, Arnal M, de Miguel MJ, Revilla M, Martínez D, et al. Spatial distribution and risk factors of Brucellosis in Iberian wild ungulates. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:46.

- Lindstrom E. The role of medium-sized carnivores in the Nordic boreal forest. Finnish Game Research. 1989;46:53–63.

- Alton GG, Jones LM, Pietz DE. Laboratory techniques in brucellosis. Monogr Ser World Health Organ. 1975;55:1–163.

- Wang Q, Zhao S, Wureli H, Xie S, Chen C, Wei Q, et al. Brucella melitensis and B. abortus in eggs, larvae and engorged females of Dermacentor marginatus. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2018;9:1045–8.

- Maquart M, Le Flèche P, Foster G, Tryland M, Ramisse F, Djønne B, et al. MLVA-16 typing of 295 marine mammal Brucella isolates from different animal and geographic origins identifies 7 major groups within Brucella ceti and Brucella pinnipedialis. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:145.

- Li S, Hu X. Serological investigation on brucellosis of cattle and sheep in Nilka County. Chinese Livestock and Poultry Breeding. 2017;4:41–3.

- Davis DS, Boeer WJ, Mims JP, Heck FC, Adams LG. Brucella abortus in coyotes. I. A serologic and bacteriologic survey in eastern Texas. J Wildl Dis. 1979;15:367–72.

Figure

Cite This ArticleOriginal Publication Date: 3/5/2020

1These authors contributed equally to this article.

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario