Remembering the 1918 Influenza Pandemic

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the 1918 influenza (flu) pandemic that swept the globe in what is still one of the deadliest disease outbreaks in recorded history.

It is estimated that about 500 million people or one-third of the world’s population became infected with this virus, and the number of deaths was estimated to be at least 50 million worldwide with about 675,000 occurring in the United States. The pandemic was so severe that from 1917 to 1918, life expectancy in the United States fell by about 12 years, to 36.6 years for men and 42.2 years for women. There were high death rates in previously healthy people, including those between the ages of 20 and 40 years old, which was unusual because flu typically hits the very young and the very old more than young adults.

The Emerging Pandemic

The 1918 flu pandemic occurred during World War I; close quarters and massive troop movements helped fuel the spread of disease.

In the United States, unusual flu activity was first detected in military camps and some cities during the spring of 1918. For the U.S. and other countries involved in the war, communications about the severity and spread of disease was kept quiet as officials were concerned about keeping up public morale, and not giving away information about illness among soldiers during wartime. These spring outbreaks are now considered a “first wave” of the pandemic; illness was limited and much milder than would be observed during the two waves that followed.

Deadly Second Wave and Third Waves

In September 1918, the second wave of pandemic flu emerged at Camp Devens, a U.S. Army training camp just outside of Boston, and at a naval facility in Boston. This wave was brutal and peaked in the U.S. from September through November. More than 100,000 Americans died during October alone. The third and final wave began in early 1919 and ran through spring, causing yet more illness and death. While serious, this wave was not as lethal as the second wave. The flu pandemic in the U.S. finally subsided in the summer of 1919, leaving decimated families and communities to pick up the pieces. Scientists now know this pandemic was caused by an H1N1 virus, which continued to circulate as a seasonal virus worldwide for the next 38 years.

Limited Care and Control Efforts in 1918

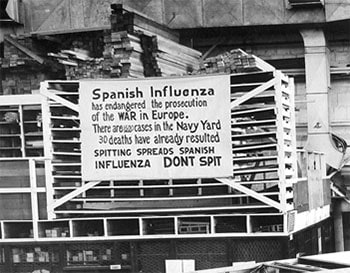

In 1918, scientists had not yet discovered viruses so there were no laboratory tests to diagnose, detect, or characterize flu viruses. Prevention and treatment methods for flu were limited. There were no vaccines to protect against flu virus infection, no antiviral drugs to treat flu illness, and no antibiotics to treat secondary bacterial infections like pneumonia. Efforts to prevent the spread of disease were limited to non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs), including promotion of good personal hygiene, and implementation of isolation, quarantine, and closures of public settings, such as schools and theaters. Some cities imposed ordinances requiring face masks in public. New York City even had an ordinance that fined or jailed people who did not cover their coughs.

Preparing For the Next Pandemic

Since the 1918 pandemic, tremendous advancements have been made in the world’s understanding and treatment of flu, but flu viruses continue to pose a serious public health threat. A vast reservoir of flu viruses circulating in animals—mainly birds–pose an ever-present threat for the emergence of another flu pandemic. For more than 60 years, CDC has worked to address the continuing threat of flu and prepare for the next pandemic.

Flu viruses with pandemic potential can now be detected through a global influenza surveillance system that includes 114 World Health Organization member states. CDC’s Influenza Division is one of 6 global influenza collaborating centers, helping to monitor and track flu activity worldwide as well as prepare candidate vaccine viruses that can be used to make vaccine. CDC also works with public health partners to monitor and investigate human infections with animal flu viruses. CDC conducts ongoing studies of both human and animal flu viruses in the laboratory to better understand the characteristics of these viruses. CDC also supports state and local governments across the United States and works with the World Health Organization (WHO) and partner countries to increase flu surveillance capabilities and collaborate on pandemic planning.

Seasonal flu vaccines to prevent flu infection are made annually, and pre-pandemic flu vaccines also are produced and stored by the U.S. federal government for possible use during a pandemic event Antiviral drugs used to treat seasonal flu illness are a potential tool for treatment during a flu pandemic. Another major advance since the 1918 pandemic is the introduction of antibiotics for treating secondary bacterial infections such as pneumonia. Some of the many other medical tools introduced since 1918 are ventilators and intensive care units for treating patients, and personal protective equipment such as gloves, gowns and masks which are now standard to protect health care workers from infection.

CDC also is working to minimize the impact of future flu pandemics by supporting research that can enhance the use of community mitigation measures (i.e., temporarily closing schools, modifying, postponing, or canceling large public events, and creating physical distance between people in settings where they commonly come in contact with one another). These non-pharmaceutical interventions continue to be an integral component of efforts to control the spread of flu, and in the absence of flu vaccine, would be the first line of defense in a pandemic. Visit Community Mitigation Guidelines to Prevent Pandemic Influenza — United States, 2017

There is still much to do to be ready for the next flu pandemic. There’s a need for more broadly effective vaccines that can be made quicker. The global infrastructure to produce and distribute flu vaccines also must be improved. More effective, and less costly, flu treatment drugs are needed. It is also important to improve the surveillance of flu viruses in animals.

In the past 100 years, we’ve come a long way in developing methods to track, prevent and treat flu, but we still have a long way to go. As America’s premier public health agency, CDC is working with its public health partners to address remaining gaps, increase our pandemic preparedness, and stay one step ahead of the next pandemic.

Visit CDC’s Pandemic Influenza website for more information about past pandemics.

.png)

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario