| MercatorNet |October 3, 2017| MercatorNet |

China’s regional fertility

Some regions are suffering more than others.

China has an exceptionally low overall fertility rate. It was 1.2 according to the census of 2010, and 1.05 according to China’s 2016 State Statistical Bureau data as reported by Liang Jianzhang and Huang Wenzheng in a recent Caixin article. Both figures are well below the generally accepted replacement level of 2.1.

The easing of the one-child policy, which was amended in early 2016 to allow all Chinese families to have two children, helped increase the number of births to 17.86 million in 2016, an increase of 7.9 percent from 2015 according to state media reports citing China's National Health and Family Planning Commission. Other data released by China's National Bureau of Statistics recorded a slightly higher figure of 18.46 million births in 2016.

All of China faces demographic issues as a result of sustained low fertility, and the increase in births is far less than what government officials were hoping. However, China is a big country and it is important to remember that its fertility rate also varies between regions, meaning that some areas will encounter the problems that low fertility will inevitably create earlier than others, with serious implications for economic growth and regional stability in those areas.

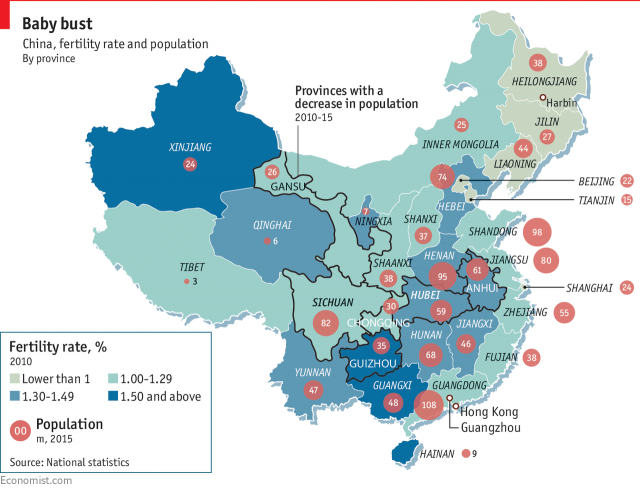

The Economist recently published this map showing four categories of fertility within China:

It includes:

1. Areas of ultra-low fertility (rates of less than 1). These are three mega-cities, Beijing, Shanghai and Tianjin, and three provinces in the north-east, sometimes called Manchuria, where the one-child policy was applied most strictly. They have a total population of 170m.

2. Areas where fertility is between 1 and 1.29. These include provinces on China’s populous coastline, as well as the huge Sichuan basin in western China. They are overwhelmingly Han areas, so had few exceptions to the one-child policy. They were also the places where China’s growth and urbanisation took off quickest after 1980, so have relatively few rural dwellers. This is the largest category, with 600m people.

3. Provinces with fertility rates between 1.3 and 1.49. Many, such as Henan, Hunan and Anhui, are just inland from the coast. They, too, are populous (460m in total) and mostly Han but have fewer city-dwellers: more than half of the populations of Hunan and Anhui is rural. This group also includes several provinces with lots of members of minorities, such as Ningxia, in the north-west, which is a third Muslim.

4. Areas with rates above 1.5, which tend both to be more rural and to have big minority populations, such as Guangxi. These have a total population of 116m.

The main reason for the variance is that the one-child policy was enforced differently in different areas. Ethnic minorities, such as Tibetans or Uighurs (the largest group in the western province of Xinjiang), were never subject to it. Minorities, who account for 8% of the population nationwide, were usually allowed two children in urban areas and three or four in rural ones. In addition, in most rural areas, everyone, including the majority Han group, was allowed two children.

Lower fertility areas tend to have an even bigger excess of boys over girls than is the norm and are ageing more quickly. This affects the regional ability to support these people. However, bigger cities such as Beijing, Shanghai and Tianjin which have ultra-low fertility are still able to attract young workers, helping combat dependency ratios. As these cities are also rich, they have better hospitals, social services and schools to help cope with their demographic problems.

One of the most affected areas is the north-east. The Economist reports:

The north-east is China’s rust belt, a place of depleted coal mines and decayed steel mills. It has had low fertility for decades, falling below replacement levels as long ago as 1982, much earlier than elsewhere (and before the one-child policy even began). It also implemented the policy especially strictly because it is dominated by state-owned industries which decreed that people who had a second child would lose their jobs. “Who would risk it?” asks a former steel worker. The area’s high wages used to attract migrants from elsewhere in China. But since 2000, when heavy industry ran into trouble, it has suffered a net outflow of over 2m people.…The result is a big problem for the national government. Even now, it is having to bail out some provincial pension funds. But the threat is also philosophical. The Communist Party has long sought to narrow economic differences and erase local political distinctions because it is terrified of regional challenges. It thinks the only way to keep China together is to impose strong central control. If it is right, its failure to deal with demographic problems is setting back that cause.

Over the next 15 years the aging of the Chinese population will only accelerate, increasing pressure on social security and public services. At the same time, the working-age population will shrink, damaging economic growth and reducing the tax income required to support the elderly.

So far, the move to a two-child policy hasn’t helped much. Chinese people growing up nowadays may not know any brothers, sisters, uncles, aunts or cousins and have grown up believing that one child is best after 30 years of propaganda. For instance, freelance writer Li Yue, an only child, commented last year:

Many people have been brainwashed by one-child policy propaganda, including my mom. When I told her I was having a second child, she thought it was unacceptable. She didn't call me or talk to me for a month.Before my first daughter came into the world, I only planned to have one baby. But when I saw my daughter, the joy, the happiness made me want to have more babies. Now, my mom loves my younger daughter very much. She has moved to our place to help look after her. And she has even started to persuade other people to have a second child.'

This mentality, enforced by the Chinese government for so many years, is now creating big problems for it. It will be hoping more people adopt the mentality of Li Yue.

October 3, 2017

Another mass shooting in the United States. This time, 59 people are dead, plus the deranged killer, who shot himself. There seems to be no legislative will to stiffen America's gun laws. But is ready availability of guns the whole story? What about the rage within the killers? Where does that come from? We explore this issue in today's lead story.

Hey, another thing. From past surveys we've learned that some of our readers can't get enough of MercatorNet and like the daily emails. Some would be content with a weekly selection of the best stories of the week. We've finally organised this. Yay! Just click below if you want to update your preferences.

Hey, another thing. From past surveys we've learned that some of our readers can't get enough of MercatorNet and like the daily emails. Some would be content with a weekly selection of the best stories of the week. We've finally organised this. Yay! Just click below if you want to update your preferences.

Michael Cook

Editor

MERCATORNET

‘An act of pure evil’

By Michael Cook

Are rifles or relationships at the bottom of the madness in Las Vegas

Read the full article

Read the full article

Guide to the classics: Dante’s Divine Comedy

By Frances Di Lauro

It is a comedy because it begins badly for the protagonist but ends well.

Read the full article

Read the full article

The worm that is killing married love

By Carolyn Moynihan

Men and women are attracted to difference, not sameness.

Read the full article

Read the full article

China’s regional fertility

By Shannon Roberts

Some regions are suffering more than others.

Read the full article

Read the full article

Who were the Vikings?

By Clare Downham

Never the pure-bred master race white supremacists like to portray.

Read the full article

Read the full article

Playboy was dedicated to replacing the faithful married man with a rakish figure

By Caroline Farrow

Hugh Hefner can’t be blamed for internet porn, but that doesn’t make his career harmless.

Read the full article

Read the full article

Quebec moves slowly toward euthanasia for dementia

By Aubert Martin

A high-profile murder case has sparked a debate about whether people who cannot consent can be killed ethically

Read the full article

Read the full article

The future of food production

By Marcus Roberts

Are there alternative protein sources?

Read the full article

Read the full article

Confessions of a Millennial mum with a smartphone habit

By Veronika Winkels

What are we teaching children when they see us constantly with our phones?

Read the full article

Read the full article

The new scientific silence on child-adult sex and the age of consent

By Mark Regnerus

A disturbing push to rehabilitate sex with minors.

Read the full article

Read the full article

MERCATORNET | New Media Foundation

Suite 12A, Level 2, 5 George Street | North Strathfield NSW 2137 | AU | +61 2 8005 8605

.png)

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario