02/02/2017 09:00 AM EST

The image above shows a small section of the trachea, or windpipe, of a developing mouse. Although it’s only about the diameter of a pinhead at this stage of development, the mouse trachea has a lot in common structurally with the much wider and longer human trachea. Both develop from a precisely engineered balance between […]

Snapshots of Life: Picturing the Developing Windpipe

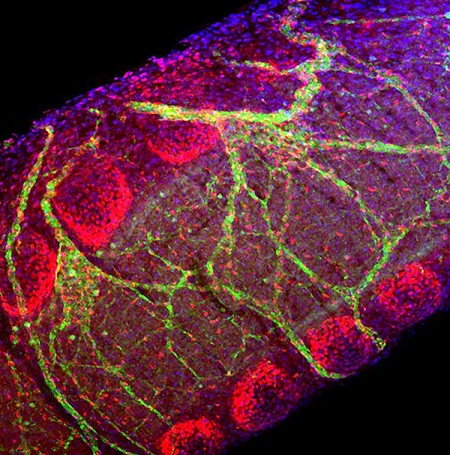

The image above shows a small section of the trachea, or windpipe, of a developing mouse. Although it’s only about the diameter of a pinhead at this stage of development, the mouse trachea has a lot in common structurally with the much wider and longer human trachea. Both develop from a precisely engineered balance between the flexibility of smooth muscle and the supportive strength and durability of cartilage.

Here you can catch a glimpse of this balance. C-rings of cartilage (red) wrap around the back of the trachea, providing the support needed to keep its tube open during breathing. Attached to the ends of the rings are dark shadowy bands of smooth muscles, which are connected to a web of nerves (green). The tension supplied by the muscle cells is essential for proper development of those neatly organized cartilage rings.

Randee Young and Xin Sun of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, snapped this image—one of the winners in the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology’s 2016 Bioart competition—in a strain of mice with perfectly formed tracheas. But the researchers also design experiments that inactivate key genes involved in trachea development, to generate mice with a range of cartilage and smooth muscle abnormalities. The hope is to learn from these mice how developmental malformations of the airway cartilage and smooth muscle can possibly contribute to pulmonary disease later in life in people.

The researchers also use mice to study a rare human condition called congenital tracheomalacia. For kids born with this condition, the walls of their windpipes are abnormally soft, floppy even, and prone to collapsing while coughing, crying, or feeding. It seems to be due to an imbalance in development of cartilage and smooth muscle.

The good news is congenital tracheomalacia usually can be controlled with careful feedings, humidified air to improve breathing, and antibiotics to fight off any infections that might arise. Kids also tend to outgrow the problem by age 2 as the trachea continues to enlarge, allowing more room for airflow.

As new parents can attest, it’s one of life’s true joys to hear a newborn’s cry as her or she breathes for the first time. It’s also heartbreaking to hear a baby with congential tracheomalacia—or any baby, for that matter—struggle to get air. The hope is that works of science and art, like this one, and the fundamental discoveries that they yield, can one day help all kids and their parents breathe a bit easier.

Links:

Congenital Tracheomalacia (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH)

Xin Sun Lab (University of Wisconsin, Madison)

BioArt (Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, Bethesda, MD)

NIH Support: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

.jpg)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario