Snapshots of Life: Stronger Than It Looks

Credit: Olivier Duverger and Maria I. Morasso, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, NIH

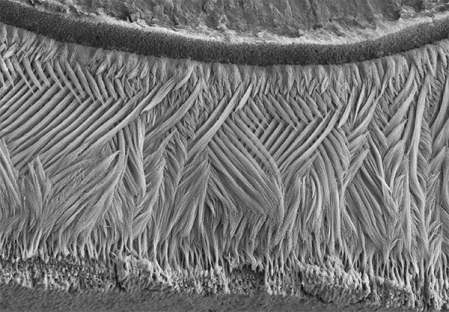

If you went out and asked folks what they’re seeing in this picture, most would probably guess an elegantly woven basket, or a soft, downy feather. But what this scanning electron micrograph actually shows isn’t at all soft: it is the hardest substance in the mammalian body—tooth enamel!

This exquisitely detailed image—a winner of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology’s 2015 BioArt competition—was generated by Olivier Duverger and Maria Morasso of NIH’s National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Before placing a sample of mouse dental enamel under the microscope, they treated it briefly with acid in order to reveal how the tissue’s mineralized rods are interwoven in a manner that gives teeth both strength and flexibility.

The NIH researchers are among those working to solve a longstanding mystery: how exactly does dental enamel, which starts out as a soft, lattice-like organic matrix in the early stages of tooth development, end up as the hard, mineralized tissue that covers our teeth? Recently, they uncovered unexpected links between structural elements in dental enamel and hair. It turns out that a specific hair keratin is also an important component in the sheath surrounding the enamel’s rods. As a result, people with an inherited hair disorder caused by a mutation in the gene that codes for this keratin also have weakened dental enamel, and are particularly prone to tooth decay [1].

While tremendous progress has been made over the last half century in preventing tooth decay, it remains a widespread public health problem in the United States [2]. Learning more about how dental enamel forms could foster better strategies to prevent cavities and possibly even to regenerate decayed enamel, reducing the need for fillings and crowns. Any of us who have spent time in a dentist’s chair would be happy to know how research could help our own teeth to have a better chance of lasting a lifetime!

References:

[1] Hair keratin mutations in tooth enamel increase dental decay risk. Duverger O, Ohara T, Shaffer JR, Donahue D, Zerfas P, Dullnig A, Crecelius C, Beniash E, Marazita ML, Morasso MI. J Clin Invest. 2014 Dec;124(12):5219-24.

[2] Dental Caries (Tooth Decay), National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, May 28, 2014.

Links:

Tooth Decay (National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research/NIH)

Laboratory of Skin Biology (National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases/NIH)

BioArt (Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, Bethesda, MD)

NIH Support: National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario