A New FDA Approval Furthers the Role of Genomics in Cancer Care

, by Norman E. Sharpless, M.D.

A recent drug approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) marks another milestone in the treatment of cancer. The action by FDA expands the growing list of approved uses for the immune checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab (Keytruda).

In this case, it is now approved to treat some adults or children with advanced cancer, regardless of the type of cancer they have, if the patient’s tumor has a large number of genetic mutations—also called a tumor mutational burden-high (TMB-H) cancer.

Because this is what is known as an accelerated approval, this new indication for pembrolizumab must be confirmed in additional studies. There also are a number of factors for oncologists to consider when deciding whether this treatment is a good option for their patients. I’ll return to those issues later.

But from a broader perspective, this new approval represents a continued march toward the use of genomics to guide cancer treatment, including for children with cancer.

It reinforces the idea that, as a routine matter, oncologists should be discussing tumor genomic testing (or “sequencing”) with their patients with advanced cancer, in particular those for whom there are no effective standard-of-care treatments. This applies to testing not only for markers like TMB that might predict response to immunotherapies, but also for genetic alterations that identify those who might benefit from a specific targeted cancer treatment.

This type of molecular profiling has helped patients with many types of cancers, even hard-to-treat cancers such as brain and pancreatic, by identifying therapies that might be more effective and less toxic for them. But it’s important to note that molecular profiling has important limitations and, clearly, there are many patients who do not benefit from this testing.

This new approval for pembrolizumab marks the fourth time that FDA has approved a drug to be used in a “tissue-agnostic” manner—that is, for any cancer type—based solely on the results of molecular testing. Given that there are now many approved cancer therapies whose use requires genomic testing (via what are known as “companion diagnostics”), I believe that tumor genomic profiling should be strongly considered for all patients with advanced cancers for which no known effective treatments currently exist.

Given this increasing role of genomic testing in cancer care, it is important to note that many patients do not benefit from molecularly targeted treatments because they are never offered that testing.

For example, a recent review in lung cancer, where genomic testing is particularly critical for selecting the most appropriate treatments, found that 10%–40% of patients are not being tested for molecular alterations that predict response to FDA-approved therapies, even though such testing is recommended by clinical guidelines.

This lack of molecular testing, which can lead to the use of treatments with the potential to markedly improve how long patients live, is concerning. At NCI, we’re particularly worried about the possibility that less genomic testing in patients from underserved populations could further exacerbate existing cancer-related health disparities.

Learning about Cancer and Tumor Mutational Burden

Having a TMB-H tumor is not a guarantee that pembrolizumab will be effective, but it is an opportunity, based on a robust evidence base that was developed in part by NCI-supported research and investigators.

It’s also important to note that this is not the first tissue-agnostic FDA approval for pembrolizumab. In May 2017, it was approved to treat any cancer that has specific genetic alterations that affect a cell’s ability to repair damaged DNA, known as microsatellite instability high (MSI-H) tumors. MSI-H and TMB-H are related, with most MSI-H tumors also showing increased TMB. The converse, however, is not true—that is, many TMB-H tumors are not MSI-H.

Moreover, MSI status does not necessarily need to be established through extensive tumor sequencing, whereas TMB status generally does. So having a drug approval based on TMB is important, because it is more common in tumors than MSI-H, and thus should promote far greater adoption of tumor genomic testing.

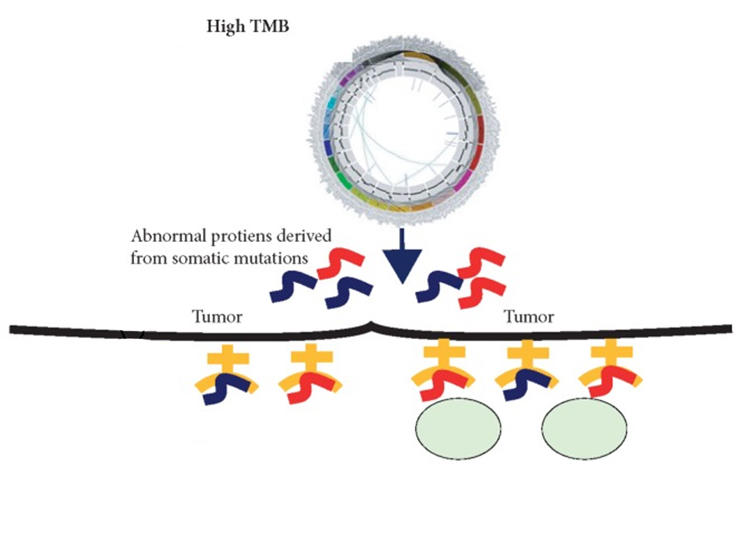

Cancer cells that are MSI-H or TMB-H tend to produce a large number of mutant proteins, which are then often displayed on the cells' surface as “neoantigens.” Since normal cells do not display such mutant proteins, the production of neoantigens can be a signal that draws the immune system’s attention. That, in turn, can increase the likelihood that treatments like pembrolizumab, which strengthen the anti-tumor immune response, will help immune cells kill those tumors.

In the clinical trial on which FDA based this new approval, called KEYNOTE-158, nearly 30% of patients with TMB-H tumors had a response to treatment—meaning they experienced at least 30% reduction in the size of their tumors—including some whose tumors disappeared completely. In contrast, only 6% of patients who were not TMB-H exhibited a response to pembrolizumab. In half of the participants who responded to the treatment, their tumors did not begin to grow again for at least 2 years!

Although patients on KEYNOTE-158 were not randomly assigned to an alternative therapy or placebo, these types of sustained treatment responses among patients with solid tumors are extremely rare with standard chemotherapies.

In addition, most participants in KEYNOTE-158 had received numerous other therapies and had no remaining treatment options known to be effective against their cancers. That’s an important point, because FDA’s new approval applies only to people with advanced cancer without any other standard treatment options.

In general, tumors in children and young adults with cancer do not have a large number of mutations and are therefore less likely to be TMB-H. But some tumors that arise in children are TMB-H, and this approval now means that such young patients have a new, potentially meaningful treatment option available to them as well.

Contribution of Genomics Research

The role of NCI-supported research in helping to identify TMB as a marker of immunotherapy response is particularly gratifying.

For example, although TMB did not even exist as a concept at the time that The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) was launched, researchers used TCGA data to perform wide-scale analyses of the relationship between tumor mutation numbers and immunotherapy response in the first place. The finding is another example of how building large, high-quality, and diverse sets of research data and making them publicly available can yield unexpected insights that lead to meaningful advances in treatment.

In addition, NCI has had a sustained and successful partnership with Foundation Medicine, the company that developed FoundationOne CDx, the test used to identify patients with TMB-H tumors for this approval. NCI-supported researchers made important contributions to the development of the technologies used by this test.

As should be expected, though, this is an extremely complicated area of research. Even with the best tests, measuring TMB and deciding what that measurement means for individual patients—in particular, estimating their likelihood of response to immunotherapy—is far from straightforward.

So NCI has been working on other fronts to make further advancements that build on the use of TMB, MSI, and other biomarkers to help guide treatment decisions. For example, NCI has partnered with Friends of Cancer Research and several other organizations on the TMB Harmonization Project, which is working to standardize how mutational burden is measured in tumors using different technologies and approaches. This project will help to ensure that TMB is used in the most effective manner possible to guide decisions about patient care.

NCI is also supporting research through the Cancer MoonshotSM on the impact of TMB and other biomarkers on how patients respond to immunotherapy. That effort is being carried out by researchers who are part of the Moonshot-funded Cancer Immune Monitoring and Analysis Centers and through a large public–private partnership called the PACT initiative.

Good News, But More To Learn

This new approval is exciting, and it will have an immediate impact on patient care. However, it’s important to stress that TMB status is just one piece of information about a tumor. Its relevance to treatment may depend on a number of factors, including a patient’s physical ability and willingness to tolerate further treatment.

In KEYNOTE-158, most patients with TMB-H tumors didn’t benefit from pembrolizumab, and a small percentage of patients whose tumors had a low TMB did respond to treatment. This suggests we still have more to learn in order to predict who will respond to immunotherapy drugs.

There is evidence, for example, that the extent of TMB required to improve the likelihood of responding to immunotherapy may vary from cancer to cancer. Information such as whether cancer type influences treatment response is important, because no cancer treatment comes without side effects, including financial toxicity.

Larger studies of pembrolizumab, which are required by FDA as part of an accelerated approval, and other research being supported by NCI can hopefully provide answers to these questions. Those answers can then help patients and their doctors have informed discussions and engage in a true process of shared decision making. For patients with advanced cancer and their families, such discussions are vital.

Especially during these hectic times, one can become cynical. But as I’ve said previously, NCI is committed to addressing the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic while also supporting the research required to address the most pressing needs for those with cancer and heralding important progress. The expanding role and value of immunotherapy as a cancer treatment is good news for patients, and that’s something I think is worth celebrating.

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario