Volume 25, Number 11—November 2019

Research

Nasopharyngeal Pneumococcal Density during Asymptomatic Respiratory Virus Infection and Risk for Subsequent Acute Respiratory Illness

On This Page

Tables

Article Metrics

Leigh M. Howard, Yuwei Zhu, Marie R. Griffin, Kathryn M. Edwards, John V. Williams, Ana I. Gil, Jorge E. Vidal, Keith P. Klugman, Claudio F. Lanata, and Carlos G. Grijalva

Abstract

Increased nasopharyngeal pneumococcal (Streptococcus pneumoniae) colonization density has been associated with invasive pneumococcal disease, but factors that increase pneumococcal density are poorly understood. We evaluated pneumococcal densities in nasopharyngeal samples from asymptomatic young children from Peru and their association with subsequent acute respiratory illness (ARI). Total pneumococcal densities (encompassing all present serotypes) during asymptomatic periods were significantly higher when a respiratory virus was detected versus when no virus was detected (p<0.001). In adjusted analyses, increased pneumococcal density was significantly associated with the risk for a subsequent ARI (p<0.001), whereas asymptomatic viral detection alone was associated with lower risk for subsequent ARI. These findings suggest that interactions between viruses and pneumococci in the nasopharynx during asymptomatic periods might have a role in onset of subsequent ARI. The mechanisms for these interactions, along with other potentially associated host and environmental factors, and their role in ARI pathogenesis and pneumococcal transmission require further elucidation.

Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus) is one of the most important bacterial causes of pneumonia among children and adults worldwide (1–3). Nasopharyngeal pneumococcal colonization is common in young children and represents a critical initial step in the progression to invasive disease (4,5). Increases in the density of pneumococci in the nasopharynx have been associated with the onset of respiratory illness (6,7) and might also play a role in transmission of bacteria to others (8). Several studies have found higher nasopharyngeal pneumococcal densities in patients with pneumonia than in healthy controls. However, no specific level of pneumococcal density has been identified that can establish the diagnosis of pneumococcal pneumonia (9–11).

The specific factors that drive increases in nasopharyngeal pneumococcal density that might lead to pneumonia or other invasive disease are not well characterized. Although an increase in density might represent expansion of a single preexisting serotype, it could also represent acquisition of a new colonizing pneumococcal serotype. New acquisition has been temporally associated with the acute onset of invasive disease (12,13). Co-detection of respiratory viruses has also been associated with increases in pneumococcal density during periods of acute respiratory illness (ARI), pneumonia, or both (6,7,14,15), suggesting that respiratory viruses and pneumococci might work synergistically in pneumonia and invasive disease pathogenesis (16–20). In addition, younger children have been shown to have higher pneumococcal densities than older children, whereas children who had received pneumococcal conjugate vaccines or lived in vaccinated communities were reported to have lower pneumococcal densities (21,22).

Respiratory viruses are frequently detected in the nasopharynx of young children during asymptomatic periods (23–26). A recent cross-sectional study of children 4–7 years of age indicated similar pneumococcal densities in asymptomatic children who had respiratory viruses detected and in children with viral upper respiratory illness (27). However, whether viral detection or duration of viral carriage during asymptomatic periods is associated with increases in nasopharyngeal pneumococcal density or subsequent ARI risk is unclear. This assessment requires longitudinal follow-up of individual young children. Our goal was to assess the association between viral detection and pneumococcal density during asymptomatic periods and determine whether viral–pneumococcal interactions during these periods predisposed to subsequent symptomatic ARI among young children.

Study Design and Setting

The Respiratory Infections in Andean Peruvian Children (RESPIRA-Peru) study is a prospective cohort study conducted in the Province of San Marcos, Department of Cajamarca, located in the northern highlands of Peru. Malaria is not endemic in this high-altitude study community (median altitude of study households 2,726 m). The population is primarily rural with low income and limited access to healthcare services, as previously described (6,7,16,23,28–34). Nearly all residents of San Marcos descended from the same ethnic group of Spanish people who mixed with the local Quechua population. During May 2009–September 2011, enrolled children <3 years of age residing in the study area were prospectively assessed for ARI symptoms during weekly household visits. An ARI episode was defined as the presence of either cough or fever. This definition of ARI has been applied in many large surveillance studies (35,36). Although fever alone is not highly specific for the diagnosis of ARI, it is well established that fever is often the only sign of ARI, especially in young children (35). In addition to cough and fever, we collected data on other respiratory signs and symptoms, including rhinorrhea, ear pain, malaise, tachypnea, nasal flaring, stridor, wheezing, and accessory muscle retractions. We considered a child to be asymptomatic if the child had rhinorrhea alone or no ARI symptoms.

The 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) was introduced in the study region in late 2009 in a 2+1 schedule (2 primary doses at 3 and 5 months of age and a booster dose at 12 months). Very few children enrolled in 2009 had received any PCV7 doses at the time of enrollment. By the end of the study (September 2011), 62% of the study cohort had received >1 PCV7 dose (30). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Vanderbilt University (Nashville, Tennessee, USA) and the Instituto de Investigacion Nutricional (Lima, Peru).

Respiratory Sample Collection and Testing

We collected nasopharyngeal swabs from each child monthly, whether or not ARI symptoms were present, and tested the swabs at Emory University (Atlanta, GA, USA) by bacterial culture for pneumococcal identification and quantitative PCR (qPCR) for pneumococcal density determinations (6,7,16,29,31). We also randomly selected a subset of nasopharyngeal samples collected during asymptomatic periods, >8 days apart from an ARI episode, to undergo real-time reverse transcription PCR (rRT-PCR) viral testing at Vanderbilt University for influenza virus (types A, B, and C), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), human metapneumovirus (MPV), rhinovirus (HRV), adenovirus (AdV), and parainfluenza virus (PIV) types 1–3 (23,32). Because detections of respiratory viruses other than HRV and AdV were infrequent in nasopharyngeal samples collected during those asymptomatic periods (23), we classified viral detections into distinct groups: HRV only; AdV only; sole detection of other virus (influenza, RSV, MPV, or PIV); co-detection of >1 respiratory virus; and no virus detected.

Statistical Analysis

We transformed pneumococcal density values to stabilize their variance, as previously described (6,7), by applying log10(x + 1) transformation to colonization density values, where x represents the measured density. We performed unadjusted group comparisons by using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, Kruskal-Wallis test, or median test with Bonferroni adjustments, as appropriate. We used multivariable linear quantile mixed effects regression to model the median of log-transformed pneumococcal density against viral detection group, with random effects to account for correlation among multiple measurements collected from the same child. Other covariates included age at the time of sample collection, sex, recent exposure to antibiotics (i.e., aminopenicillins, cephalosporins, co-trimoxazole, chloramphenicol, or furazolidone within the previous 7 days), pneumococcal vaccination status (receipt of >1 dose of PCV7), and calendar month. Because viral infections could lead to rhinorrhea, we did not directly include this variable in our main regression model, and rhinorrhea was considered as a potential variable in the causal pathway between viral infections and pneumococcal density changes. To examine the association of pneumococcal densities during asymptomatic periods with the risk for subsequent ARI, we conducted a survival analysis by using a frailty model and accounted for repeated measurements from individual children. Because severe ARI occurred uncommonly in this household surveillance study, we did not stratify the outcome variable (ARI) by severity (28). For this assessment, follow-up extended from the date of an asymptomatic nasopharyngeal sample collection (>8 days after the last day of ARI symptoms) through the earliest of the following: ARI, the collection of another nasopharyngeal sample, or 60 days after collection of the initial asymptomatic nasopharyngeal sample. These censoring criteria were implemented on the basis of our monthly nasopharyngeal collection strategy and the anticipated transient duration of colonization with an individual serotype in young children, typically 6–8 weeks or less (37–40). Because viral infection or its manifestation as rhinorrhea could modify the risk for subsequent ARI (41), alternate models accounted for either viral infections or rhinorrhea in addition to the aforementioned covariates. We applied restricted cubic splines (RCS) to log-transformed pneumococcal densities in our frailty model to relax the assumption of linearity in our models (42,43). The estimated effects of RCS-transformed densities are presented in figures. The proportional hazards assumption of the frailty model was examined and satisfied by using a Schoenfeld’s global test. Statistical analyses were done in Stata version 14.2 () and R version 3.5.0 (), including lqmm and survival packages.

Pneumococcal Colonization and Viral Detections

In total, 849 nasopharyngeal samples collected during asymptomatic periods from 480 children underwent both viral testing and pneumococcal density determinations (Appendix Figure 1). Relevant demographic characteristics of study children are shown in the Table. Pneumococcus was detected in 566/849 (67%) nasopharyngeal samples from asymptomatic children. At least 1 respiratory virus was detected in 357/849 (42%) samples from asymptomatic children, most commonly HRV (31%) and AdV (11%), whereas detections of influenza, MPV, PIV, and RSV in asymptomatic children were uncommon (<3%), as previously reported (23).

Co-detection of >1 respiratory virus occurred in 48/849 (6%) samples. HRV was present in 40/48 (83%) co-detections, most commonly in combination with AdV, with or without an additional virus (36/40 [90%]). Colonization with pneumococcus was more common in samples in which >1 respiratory virus was detected (280/357 [78%]) than in those in which a respiratory virus was not detected (286/492 [58%]) (p<0.001). Rhinorrhea was reported in 219/357 (61%) children in whom a virus was detected, compared with 227/492 (46%) in whom a virus was not detected (p<0.001). At least 1 respiratory virus was detected in 219/446 (49%) children with rhinorrhea, compared to 138/403 (34%) without rhinorrhea. Antibiotic exposure preceding collection of each asymptomatic nasopharyngeal sample was uncommon, occurring in only 12/849 (1%) samples (antibiotic exposure was unknown in 9/849 samples [1%]).

Pneumococcal Densities and Associated Factors

In unadjusted comparisons, log10-transformed pneumococcal densities were higher during asymptomatic periods when >1 respiratory virus was detected (median 4.95 [interquartile range (IQR) 3.11–6.35]) than when no respiratory viruses were detected (median 3.35 [IQR 0–4.95]; p<0.001). When densities were examined according to detection of specific viruses, densities differed significantly by viral group (p<0.001); the highest densities were observed in the HRV-only group. In Bonferroni-adjusted pairwise median comparisons, pneumococcal densities were significantly higher when HRV only (median 5.18 [IQR 3.40–6.43]; p<0.001) or viral co-detections (median 4.71 [IQR 3.46–6.35]; p = 0.003) were present compared with samples that were virus-negative (3.35 [IQR 0–4.95]). In Bonferroni-adjusted median comparisons, pneumococcal density from samples with AdV-only infection (median 4.39 [IQR 3.15–6.08]) was not significantly different from that from samples with no respiratory viruses detected (p = 0.087).

In the multivariable mixed effects quantile regression model, pneumococcal densities during asymptomatic periods were not associated with age, sex, antibiotic exposure, or history of pneumococcal vaccination. However, detection of any (>1) virus was significantly associated with higher log10-transformed pneumococcal densities (Appendix Table 1). The addition of rhinorrhea, a common manifestation of viral infections, to the model attenuated the observed association between viral infections and pneumococcal density, but the association remained statistically significant.

We compiled violin plots of predicted pneumococcal densities according to detection of any respiratory virus as estimated from the multivariable linear quantile mixed effects model (Figure 1). When specific viruses were examined in multivariable analyses, detection of HRV only, detection of AdV only, or co-detection of >1 virus was significantly associated with increased pneumococcal densities compared with densities in samples that were virus-negative. We observed no significant association between detection of other less frequently detected viruses (RSV, PIV, influenza, MPV) and pneumococcal densities (Appendix Table 2). As in the main analysis, the addition of rhinorrhea to the model slightly attenuated, but did not eliminate, the observed associations. We compiled predicted densities associated with specific viral infections as estimated from the multivariable linear quantile mixed effects model (Figure 2).

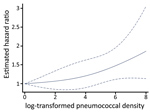

Exploration of Asymptomatic Pneumococcal Densities and Risk for Subsequent ARI

We explored the association of pneumococcal density during asymptomatic periods and the time to next ARI by using log-transformed pneumococcal density as the exposure of interest and ARI as the outcome in a frailty model. Compared with the lowest pneumococcal density, increases in pneumococcal density were significantly associated with increased incidence of subsequent ARI (Figure 3; Appendix Table 3) (p<0.001). Younger age, receipt of >1 PCV7 dose, and detection of >1 respiratory virus during asymptomatic periods were significantly associated with lower incidence of ARI. In addition, sample collection during the middle months of spring (October and November) was associated with lower incidence of subsequent ARI. Similar findings were observed when rhinorrhea was included in the model instead of viral detection (Appendix Table 4, Figure 2), suggesting that the association between viral detection and ARI might be at least partially mediated by rhinorrhea.

Our findings demonstrate that viral detections during asymptomatic periods are associated with increases in nasopharyngeal pneumococcal colonization density, and further, that higher pneumococcal density during asymptomatic periods is associated with subsequent onset of an ARI. These findings expand upon earlier observations from our group and others that increases in nasopharyngeal pneumococcal colonization density are associated with symptomatic respiratory illness and pneumonia and with the detection of respiratory viruses during ARI periods (6,7,14,15). We now report that those associations are not restricted to periods of symptomatic disease and demonstrate an increased risk for ARI with increasing pneumococcal density during asymptomatic periods as well. Of interest, increased pneumococcal density was associated with the risk for subsequent ARI in a nonlinear manner and appeared particularly evident at higher pneumococcal densities (>104). These findings suggest that asymptomatic viral infection during asymptomatic periods might present colonizing pneumococci with an opportunity to expand.

Most ARI episodes in our study were mild, self-limited without antibiotic use, and associated with respiratory virus detection (28). Our finding that increases in pneumococcal density during asymptomatic episodes were associated with increased likelihood of subsequent onset of these mostly mild, viral ARI might suggest a contributing role of colonizing pneumococci in these illnesses. Of note, this association only became significant at the highest levels of pneumococcal density. A previous study of young children with nasopharyngeal pneumococcal colonization indicated that higher colonization density was associated with high levels of markers of nasopharyngeal inflammation compared with children with lower-density colonization (44). We postulate that increased nasopharyngeal inflammation from increased pneumococcal density might facilitate viral infection of an exposed susceptible person. The hypothesis that nasopharyngeal pneumococcal colonization patterns and density might influence subsequent onset of nonpneumococcal ARI is also consistent with our observation that children who had received >1 PCV vaccination had a reduced risk for ARI following asymptomatic viral detection compared with unvaccinated children.

A recent study by DeMuri et al. (27) examined colonization density with pneumococci and other respiratory bacteria during asymptomatic periods in children 4–7 years of age. They found that the densities of pneumococcus, Moraxella catarrhalis, and Haemophilus influenzae all increased when respiratory viruses were detected, although the study design did not allow determination of subsequent ARI risk (27). In that study, the association of viral detection and nasopharyngeal bacterial density was strongest with pneumococcus; pneumococcal densities approached those observed during periods of viral upper respiratory illness. HRV, coronaviruses, and viral co-detections (≥1 virus present) were also significantly associated with higher densities than when no virus was detected. Detection of AdV in their patients was not significantly associated with increased pneumococcal densities during asymptomatic periods, but those observations were limited to only 4 AdV-positive samples.

Although both viral detection and rhinorrhea were associated with increased pneumococcal density, both were also associated with a lower incidence of subsequent ARI. Specifically, children with viral infection or rhinorrhea had a lower incidence of subsequent ARI than children without viral infection or rhinorrhea. The mechanism of this association is unclear but might involve the phenomenon of viral interference, in which infection with 1 virus prevents or mitigates infection with a different virus, perhaps through the induction of proinflammatory cytokines or other immune mediators (41), because the presence of rhinorrhea might indicate a viral infection with a virus detected or not detected in our study. Rhinitis has also been shown to occur after intranasal inoculation of pneumococcus in healthy adults and in mouse models (45), and nasal discharge has been associated with pneumococcal detection even in the absence of respiratory viral infection (46), suggesting that an inflammatory response might be an important component of early pneumococcal colonization, which might have important host consequences. Furthermore, several studies have also demonstrated the role of normal airway mucus and nasal secretions in lining epithelial surfaces and trapping and removing pathogens from the airway through mucociliary clearance (47,48), potentially providing an effective barrier to acquisition of new respiratory viruses, bacteria, or both.

In spite of the strengths of our longitudinal design, our study has several limitations. Because detection of viruses other than HRV and AdV during asymptomatic periods was uncommon in our cohort, the power to detect associations with these other specific viruses and pneumococcal densities was low. HRV was detected in >80% of samples in which >1 virus was detected, limiting inferences about co-detections with other viruses. Because of enhanced sensitivity of rRT-PCR for detection of respiratory viruses relative to culture, it might be difficult to interpret the clinical significance of detection of HRV and AdV by PCR in asymptomatic children (i.e., whether these detections might represent prolonged shedding from a prior illness or a recent asymptomatic infection). The study was conducted in a rural region in which the incidence of pneumonia is higher than national rates (28,49). However, incidence of other common respiratory diseases, such as otitis media, sinusitis, and other types of respiratory illnesses, was not available. Highest densities were observed during the 2009 mid-spring season, but examination of several consecutive seasons would be useful to clarify the role of seasonality in our observations. In our assessment of the role of colonization density during asymptomatic periods on the risk for subsequent ARI, we did not systematically assess for pneumococcal colonization or density during the subsequent ARI, so direct density comparisons were not possible between the asymptomatic and subsequent ARI periods. Furthermore, we must note that several factors might play a role in increases in pneumococcal colonization density. A recent study from Kenya found that increases in density associated with viral detection were modest relative to the baseline variation in density in individual patients (50) and postulated that other factors, such as the host immune response to previous viral infections (6,7,27), also play an important role in the association between high levels of pneumococcal density and risk for subsequent ARI. However, the potential influence of immune, genetic, or other environmental factors on subsequent ARI risk was not measured in our study. Also, the associations observed with pneumococcal density might be serotype-specific, but serotype information was not available for those samples from patients with subsequent ARI. Furthermore, interactions between pneumococcus and other colonizing nasopharyngeal bacteria might play an important role in the host response to pneumococcal acquisition as well as the dynamics of pneumococcal density and pathogenesis (29), but associated changes in the nasopharyngeal microbiome were not assessed in this study. The presence of an asymptomatic viral infection was associated with a lower risk for subsequent symptomatic ARI in this study. Although we postulate that such a relationship might have a time-limited impact, our study was set up with a short follow-up time and was not designed to determine the duration of this association. Additional studies that have a longer follow-up time and are specifically designed to determine the temporality of the observed association would be useful. Future studies will assess the relationship between viral detection and serotype and density patterns over time in individual patients, along with associated changes in the respiratory microbiome during both asymptomatic and ARI periods. Finally, our study did not assess transmission patterns of colonizing pneumococci. Whether the increase in densities associated with viral detection have an impact on transmission is unclear.

In summary, we found that viral detections during asymptomatic periods are associated with increases in nasopharyngeal pneumococcal colonization density. Furthermore, we found that pneumococcal density, especially at high levels, is associated with subsequent development of ARI in young children in Peru. These findings suggest that interactions between viruses and pneumococci in the nasopharynx during asymptomatic periods might have a role in onset of subsequent ARI.

Dr. Howard is an assistant professor of pediatric infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. Her primary research interests are respiratory viral and bacterial epidemiology, with an emphasis on pneumococcal infections, antimicrobial resistance patterns among pneumococci, and the impact of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines on pneumococcal colonization dynamics in children.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the communities of San Marcos, Cajamarca, Peru, for their participation in this study. We also appreciate the approval and continuous support of the Cajamarca Health Region authorities and thank the field workers and field supervisors whose efforts allowed this study to be conducted. We further thank Sopio Chochua and Paulina A. Hawkins for their assistance in laboratory assays.

This work was supported by the Vanderbilt University Clinical and Translational Science Award (grant no. UL1 RR024975-01) from the National Institutes of Health; investigator-initiated research grants (grant nos. IIR WS1898786 [0887X1-4492] and IIR WS2079099) from Pfizer; a grant from the Thrasher Research Fund (grant no. 02832-9); and funds from the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Department of Pediatrics Turner-Hazinski and Katherine Dodd Faculty Scholars Awards, the Vanderbilt Faculty Research Scholars Program, and the Pfizer Young Investigator in Vaccine Development award. J.E.V. received support from the National Institutes of Health (grant no. R21AI112768-01A1).

Conflicts of interest: L.M.H. receives grant support from Pfizer. C.G.G. has served as a consultant to Pfizer, Merck, and Sanofi-Pasteur for unrelated work and received research support from Sanofi-Pasteur. M.R.G. receives grant funding from MedImmune. K.M.E. receives grant funding from Novartis in unrelated work. J.V.W. serves on a scientific advisory board for Quidel and an independent data monitoring committee for GlaxoSmithKline, neither related to the present work. C.F.L. serves as a scientific advisor to Takeda in subjects not related to the present work.

References

- Cevey-Macherel M, Galetto-Lacour A, Gervaix A, Siegrist CA, Bille J, Bescher-Ninet B, et al. Etiology of community-acquired pneumonia in hospitalized children based on WHO clinical guidelines. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;168:1429–36.

- Griffin MR, Zhu Y, Moore MR, Whitney CG, Grijalva CGUS. U.S. hospitalizations for pneumonia after a decade of pneumococcal vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:155–63.

- Izadnegahdar R, Cohen AL, Klugman KP, Qazi SA. Childhood pneumonia in developing countries. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1:574–84.

- Simell B, Auranen K, Käyhty H, Goldblatt D, Dagan R, O’Brien KL; Pneumococcal Carriage Group. The fundamental link between pneumococcal carriage and disease. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2012;11:841–55.

- Bogaert D, De Groot R, Hermans PW. Streptococcus pneumoniae colonisation: the key to pneumococcal disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4:144–54.

- Fan RR, Howard LM, Griffin MR, Edwards KM, Zhu Y, Williams JV, et al. Nasopharyngeal pneumococcal density and evolution of acute respiratory illnesses in young children, Peru, 2009–2011. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:1996–9.

- Howard LM, Fan R, Zhu Y, Griffin MR, Edwards KM, Hartinger S, et al. Nasopharyngeal pneumococcal density is associated with viral activity but not with use of improved stoves among young andean children. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4:

ofx161 . - Diavatopoulos DA, Short KR, Price JT, Wilksch JJ, Brown LE, Briles DE, et al. Influenza A virus facilitates Streptococcus pneumoniae transmission and disease. FASEB J. 2010;24:1789–98.

- Albrich WC, Madhi SA, Adrian PV, van Niekerk N, Mareletsi T, Cutland C, et al. Use of a rapid test of pneumococcal colonization density to diagnose pneumococcal pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:601–9.

- Brotons P, Bassat Q, Lanaspa M, Henares D, Perez-Arguello A, Madrid L, et al. Nasopharyngeal bacterial load as a marker for rapid and easy diagnosis of invasive pneumococcal disease in children from Mozambique. PLoS One. 2017;12:

e0184762 . - Baggett HC, Watson NL, Deloria Knoll M, Brooks WA, Feikin DR, Hammitt LL, et al. Density of upper respiratory colonization with Streptococcus pneumoniae and its role in the diagnosis of pneumococcal pneumonia among children aged <5 years in the PERCH Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(Suppl_3):S317–S27.

- Auranen K, Syrjänen R, Leino T, Kilpi T. New pneumococcal carriage acquired in association with acute respiratory infection is prone to cause otitis media. PLoS One. 2016;11:

e0156343 . - Käyhty H, Auranen K, Nohynek H, Dagan R, Mäkelä H. Nasopharyngeal colonization: a target for pneumococcal vaccination. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2006;5:651–67.

- Wolter N, Tempia S, Cohen C, Madhi SA, Venter M, Moyes J, et al. High nasopharyngeal pneumococcal density, increased by viral coinfection, is associated with invasive pneumococcal pneumonia. J Infect Dis. 2014;210:1649–57.

- Vu HT, Yoshida LM, Suzuki M, Nguyen HA, Nguyen CD, Nguyen AT, et al. Association between nasopharyngeal load of Streptococcus pneumoniae, viral coinfection, and radiologically confirmed pneumonia in Vietnamese children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:11–8.

- Grijalva CG, Griffin MR, Edwards KM, Williams JV, Gil AI, Verastegui H, et al. The role of influenza and parainfluenza infections in nasopharyngeal pneumococcal acquisition among young children. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:1369–76.

- Weinberger DM, Grant LR, Steiner CA, Weatherholtz R, Santosham M, Viboud C, et al. Seasonal drivers of pneumococcal disease incidence: impact of bacterial carriage and viral activity. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:188–94.

- Ampofo K, Bender J, Sheng X, Korgenski K, Daly J, Pavia AT, et al. Seasonal invasive pneumococcal disease in children: role of preceding respiratory viral infection. Pediatrics. 2008;122:229–37.

- Talbot TR, Poehling KA, Hartert TV, Arbogast PG, Halasa NB, Edwards KM, et al. Seasonality of invasive pneumococcal disease: temporal relation to documented influenza and respiratory syncytial viral circulation. Am J Med. 2005;118:285–91.

- Shrestha S, Foxman B, Weinberger DM, Steiner C, Viboud C, Rohani P. Identifying the interaction between influenza and pneumococcal pneumonia using incidence data. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:

191ra84 . - Fadlyana E, Dunne EM, Rusmil K, Tarigan R, Sudigdoadi S, Murad C, et al. Risk factors associated with nasopharyngeal carriage and density of Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and Staphylococcus aureus in young children living in Indonesia. Pneumonia (Nathan). 2018;10:14.

- Roca A, Bottomley C, Hill PC, Bojang A, Egere U, Antonio M, et al. Effect of age and vaccination with a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on the density of pneumococcal nasopharyngeal carriage. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:816–24.

- Howard LM, Johnson M, Williams JV, Zhu Y, Gil AI, Edwards KM, et al.; RESPIRA-PERU Group. RESPIRA-PERU Group. Respiratory viral detections during symptomatic and asymptomatic periods in young Andean children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015;34:1074–80.

- Self WH, Williams DJ, Zhu Y, Ampofo K, Pavia AT, Chappell JD, et al. Respiratory viral detection in children and adults: comparing asymptomatic controls and patients with community-acquired pneumonia. J Infect Dis. 2015.

- Jartti T, Jartti L, Peltola V, Waris M, Ruuskanen O. Identification of respiratory viruses in asymptomatic subjects: asymptomatic respiratory viral infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:1103–7.

- Chonmaitree T, Alvarez-Fernandez P, Jennings K, Trujillo R, Marom T, Loeffelholz MJ, et al. Symptomatic and asymptomatic respiratory viral infections in the first year of life: association with acute otitis media development. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:1–9.

- DeMuri GP, Gern JE, Eickhoff JC, Lynch SV, Wald ER. Dynamics of bacterial colonization With Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis during symptomatic and asymptomatic viral upper respiratory tract infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66:1045–53.

- Budge PJ, Griffin MR, Edwards KM, Williams JV, Verastegui H, Hartinger SM, et al.; RESPIRA-PERU Group. A household-based study of acute viral respiratory illnesses in Andean children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33:443–7.

- Chien YW, Vidal JE, Grijalva CG, Bozio C, Edwards KM, Williams JV, et al. Density interactions among Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and Staphylococcus aureus in the nasopharynx of young Peruvian children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32:72–7.

- Grijalva CG, Griffin MR, Edwards KM, Williams JV, Gil AI, Verastegui H, et al. Cohort profile: The study of respiratory pathogens in Andean children. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:1021–30.

- Hanke CR, Grijalva CG, Chochua S, Pletz MW, Hornberg C, Edwards KM, et al. Bacterial density, serotype distribution and antibiotic resistance of pneumococcal strains from the nasopharynx of Peruvian children before and after pneumococcal conjugate vaccine 7. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016;35:432–9.

- Howard LM, Johnson M, Gil AI, Griffin MR, Edwards KM, Lanata CF, et al. Molecular epidemiology of rhinovirus detections in young children. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;3:

ofw001 . - Howard LM, Johnson M, Gil AI, Pekosz A, Griffin MR, Edwards KM, et al.; RESPIRA-PERU Group. A novel real-time RT-PCR assay for influenza C tested in Peruvian children. J Clin Virol. 2017;96:12–6.

- Wu A, Budge PJ, Williams J, Griffin MR, Edwards KM, Johnson M, et al. Incidence and risk factors for respiratory syncytial virus and human metapneumovirus infections among children in the remote highlands of Peru. PLoS One. 2015;10:

e0130233 . - Poehling KA, Edwards KM, Weinberg GA, Szilagyi P, Staat MA, Iwane MK, et al.; New Vaccine Surveillance Network. The underrecognized burden of influenza in young children. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:31–40.

- Lanata CF, Rudan I, Boschi-Pinto C, Tomaskovic L, Cherian T, Weber M, et al. Methodological and quality issues in epidemiological studies of acute lower respiratory infections in children in developing countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33:1362–72.

- Turner P, Turner C, Jankhot A, Helen N, Lee SJ, Day NP, et al. A longitudinal study of Streptococcus pneumoniae carriage in a cohort of infants and their mothers on the Thailand-Myanmar border. PLoS One. 2012;7:

e38271 . - Gritzfeld JF, Cremers AJ, Ferwerda G, Ferreira DM, Kadioglu A, Hermans PW, et al. Density and duration of experimental human pneumococcal carriage. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:O1145–51.

- Darboe MK, Fulford AJ, Secka O, Prentice AM. The dynamics of nasopharyngeal streptococcus pneumoniae carriage among rural Gambian mother-infant pairs. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:195.

- Högberg L, Geli P, Ringberg H, Melander E, Lipsitch M, Ekdahl K. Age- and serogroup-related differences in observed durations of nasopharyngeal carriage of penicillin-resistant pneumococci. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:948–52.

- Chan KF, Carolan LA, Korenkov D, Druce J, McCaw J, Reading PC, et al. Investigating viral interference between influenza A virus and human respiratory syncytial virus in a ferret model of infection. J Infect Dis. 2018;218:406–17.

- Harrell FE. Regression modeling strategies: with applications to linear models, logistic regression, and survival analysis. New York: Springer; 2001.

- Marrie RA, Dawson NV, Garland A. Quantile regression and restricted cubic splines are useful for exploring relationships between continuous variables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:511–7.e1.

- Vissers M, Ahout IM, van den Kieboom CH, van der Gaast-de Jongh CE, Groh L, Cremers AJ, et al. High pneumococcal density correlates with more mucosal inflammation and reduced respiratory syncytial virus disease severity in infants. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:129.

- Weiser JN. The pneumococcus: why a commensal misbehaves. J Mol Med (Berl). 2010;88:97–102.

- Collins DA, Hoskins A, Snelling T, Senasinghe K, Bowman J, Stemberger NA, et al. Predictors of pneumococcal carriage and the effect of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccination in the Western Australian Aboriginal population. Pneumonia (Nathan). 2017;9:14.

- Voynow JA, Rubin BK. Mucins, mucus, and sputum. Chest. 2009;135:505–12.

- Fahy JV, Dickey BF. Airway mucus function and dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2233–47.

- Rudan I, Boschi-Pinto C, Biloglav Z, Mulholland K, Campbell H. Epidemiology and etiology of childhood pneumonia. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:408–16.

- Morpeth SC, Munywoki P, Hammitt LL, Bett A, Bottomley C, Onyango CO, et al. Impact of viral upper respiratory tract infection on the concentration of nasopharyngeal pneumococcal carriage among Kenyan children. Sci Rep. 2018;8:11030.

Figures

Table

Cite This ArticleOriginal Publication Date: 9/30/2019

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario