Volume 25, Number 2—February 2019

Research Letter

Oropouche Virus–Associated Aseptic Meningoencephalitis, Southeastern Brazil

On This Page

Abstract

Oropouche fever is a neglected arthropodborne disease and zoonosis responsible for several outbreaks of a febrile disease in Central and South America. We present a clinical case of aseptic meningoencephalitis in an immunocompetent patient that resulted from Oropouche virus acquired in northern Brazil but diagnosed in a nonendemic region.

In April 2016, a 28-year-old man (S.V.) in Ribeirão Preto, southeastern Brazil, with a history of Gilbert syndrome sought care for a sudden high fever, severe 1-sided headache, vomiting, intense photophobia, stiff neck, and confusion. Seventeen days earlier, he had returned from a trip to Mosqueiro Island in northern Brazil; he received yellow fever vaccine 5 days before traveling. His 1-week visit to the island included outdoor activities that involved entrances into the native Amazon rainforest. The patient returned to Ribeirão Preto and remained asymptomatic for 10 days before becoming acutely ill with fever, chills, myalgia, headache, and dizziness. Symptoms occurred intermittently for 3 days, which prompted him to seek medical care. After evaluation, a diagnosis of dengue fever was considered. Microhematocrit was 54%, and tourniquet test was negative. Nonstructural protein (NS) 1 antigen detection test was requested, and the patient was treated with medications for his symptoms and prescribed abundant oral hydration and bed rest. Dengue fever was ruled out because NS1 antigen detection and IgM serologic testing provided negative results 6 days after initial symptom onset. Therefore, he was referred to an infectious disease outpatient clinic at another healthcare facility for further investigation. Yellow fever vaccine reaction and malaria were initially the main hypotheses, but thick blood film examination results were negative.

Seven days after initial symptom onset, the patient’s headache worsened and became left-sided and pulsatile; intense photophobia, vomiting, and fever (105.8°F) developed. No hemorrhagic manifestations were observed. He was admitted to the emergency department at the Teaching Hospital in Ribeirão Preto with nuchal rigidity; ceftriaxone was initiated.

At admission, he was confused, including attention deficits and hallucinations. Physical examination found tachypnea (27 breaths/min), heart rate 76 beats/min, and blood pressure 130/80 mm Hg; cardiopulmonary examination results were unremarkable, and the liver was palpable at 3 cm under the costal margin (spleen was not palpable) with no pain at abdominal palpation. The patient exhibited mild spasticity of lower limbs with positive Babinski sign, without focalities at neurologic exam. Because of clinical examination findings, viral meningoencephalitis emerged as a possible diagnosis, and intravenous acyclovir was started.

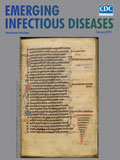

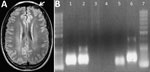

Figure. Imaging and PCR results for a 28-year-old man with Oropouche virus infection, southeastern Brazil. A) Cerebral computed tomography showing a cortical edema on the left frontal lobe (white arrow). B) Agarose...

Laboratory examination showed complete blood counts within reference ranges (hematocrit 44%; leukocytes 10,300 cells/mm3 [no left shift; lymphocytes 2,300 cells/mm3]; platelets 388,000/mm3), normal kidney function, and sodium and potassium concentrations within reference ranges. Liver enzymes were slightly elevated (aspartate aminotransferase 30 U/L [reference 15–46 U/L], alanine aminotransferase 71 U/L [reference 13–69 U/L], γ-glutamyl transferase 107 U/L [7–60 U/L]); total bilirubin was 0.73 mg/dL (reference 0.2–1.0 mg/dL). Serologic test results were nonreactive for hepatitis A, B, and C; HIV; syphilis; Epstein-Barr virus; Toxoplasma gondii; and Trypanosoma cruzi. Thorax radiograph imaging was unremarkable; cerebral computed tomography scan showed cortical edema on the left frontal lobe (Figure, panel A).

Results of a spinal tap showed a 23 cm H2O opening pressure (reference 5–20 cm H2O) with clear cerebrospinal fluid containing 45 cells/mm3 (reference <5 cells/mm3) (85% lymphocytes); protein concentration of 53 mg/dL (reference <45 mg/dL); and glucose concentration of 62 mg/dL (capillary 100 mg/dL [reference 2/3 of capillary glucose]). VDRL test results were negative, and bacterial and fungal antigens were not detected. PCR results were negative for enterovirus, herpes viruses 1 and 2, varicella zoster virus, cysticercosis, tuberculosis, and toxoplasmosis but positive for Oropouche virus (OROV) (fraction S) (1). Blood sample PCR results were also positive for OROV (Figure, panel B) (2), and indirect immunofluorescence antibody testing (Appendix) (3) confirmed OROV infection.

After 7 days of hospitalization, the patient recovered all neurologic function with no sequelae (posttreatment electromyography and magnetic resonance imaging findings were unremarkable). He was discharged and has had no additional relapses.

OROV, an RNA virus belonging to the genus Orthobunyavirus, family Peribunyaviridae, is the causative agent of Oropouche fever in humans (4). In a sylvatic cycle, OROV can be transmitted to some animals by mosquitoes and in an urban environment can be transmitted to humans by the midge Culicoides paraensis (5). Usually, humans become infected in forested areas and then can translocate the virus to an urban environment (6).

After a 4- to 8-day incubation period, fever, headache, myalgia, arthralgia, chills, photophobia, dizziness, nausea, and vomiting develop (2,6). Less frequently, patients experience rash, anorexia, retro-orbital pain, and general malaise (2,6,7). Hemorrhagic phenomena also have been described (8). Most patients recover spontaneously after 7 days, although some experience symptoms for as long as 1 month (2,6,7). Some cases can relapse after recovery; the clinical picture is similar to the initial onset or can be more severe, including aseptic meningitis (9,10). These patients may experience neck stiffness, dizziness, vomiting, lethargy, diplopia, and nystagmus, but prognosis without sequel is usually good (10).

There has been an increased concern that Oropouche fever, endemic in northern Brazil, might spread across the country by contiguous urban cycles and by human movement. Physicians working worldwide in areas to which OROV is not endemic should include this neglected disease in the differential diagnosis of acute febrile syndrome, especially in patients visiting high-risk areas for OROV transmission.

Dr. Vernal, the patient in this report, is a Chilean medical doctor working with neglected diseases in Brazil since 2013 and a PhD student in clinical medicine and a medical resident of infectious disease at University of São Paulo. His primary research interests include tropical infectious diseases with special emphasis on leprosy and tegumentary leishmaniasis.

Acknowledgment

We thank the medical and nursing staff of the infectious diseases ward, Teaching Hospital, Ribeirão Preto Medical School, University of São Paulo.

References

- Travassos da Rosa JF, de Souza WM, Pinheiro FP, Figueiredo ML, Cardoso JF, Acrani GO, et al. Oropouche virus: clinical, epidemiological, and molecular aspects of a neglected orthobunyavirus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;96:1019–30.PubMed

- Alvarez-Falconi PP, Ríos Ruiz BA. [Oropuche fever outbreak in Bagazan, San Martin, Peru: epidemiological evaluation, gastrointestinal and hemorrhagic manifestations] [in Spanish]. Rev Gastroenterol Peru. 2010;30:334–40.PubMed

- Pinheiro FP, Rocha AG, Freitas RB, Ohana BA, Travassos da Rosa AP, Rogério JS, et al. [Meningitis associated with Oropouche virus infections] [in Portuguese]. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1982;24:246–51.PubMed

Figure

Cite This ArticleOriginal Publication Date: 1/7/2019

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario