Volume 24, Number 1—January 2018

About the Cover

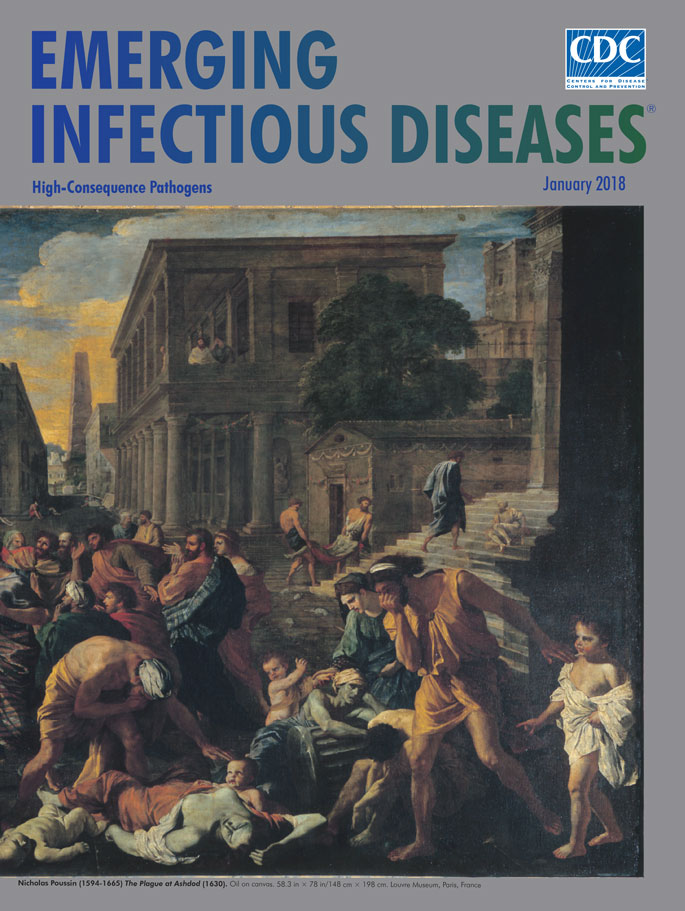

Of Rats and Men: Poussin’s Plague at Ashdod

Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665) was a brilliant French Baroque painter whose art was inspired by biblical and mythological scenes. Poussin depicts the Plague at Ashdod (1630) (Louvre Museum, Paris, France) in one of his best works, inspired by an episode from chapter 5 of the Book of Samuel. On this large canvas, rats run through buildings and among dead and dying bodies. The Book of Samuel, written during 630–540 bce , recounts the capture of the Ark of the Covenant by the Philistines, who moved it to the city of Ashdod. “Soon after receiving the Ark rats appeared in the land and death and destruction spread throughout Ashdod. The Philistines, young and old, were struck by an outbreak of tumors in the groin and died.” The Philistines sent the Ark back to Israel with a guilt offering of “five gold tumors and five gold rats,” models of the pestilences destroying the country.

This biblical text has been linked to bubonic plague by some, but not all, authors because black rats from the Far East did not reach the Near East until the 1st century bce . However, fossilized remains of Xenopsylla cheopis fleas and the R. rattus black rats have been found in the Egyptian Nile Valley, dating their arrival in the Middle East to 1350 bce . The Jewish–Roman historian Flavius Josephus (37−100 ace ) attributed the epidemic to bacillary dysenter, which can lead to hemorrhoids, his translation of the Hebrew word “opalim.” However, Josephus’ translation of the Hebrew word has been questioned. The original Hebrew text of the Book of Samuel uses two words to describe the plague’s pathology, namely techorim (tumor) and ophel (boil), both appropriate for bubonic plague.

The King James version of the Bible translates both words as “emerods” (hemorrhoids), and the New International version of the Bible translates both as “tumors.” The Septuagint, a Hebrew-to-Greek translation of the Torah made in the 3rd century in Egypt by 72 Hebrew scholars, and Saint Jerome’s translation of this Greek text into Latin, both expand on the original Hebrew by stating that the tumors were in the groin (bubo is derived from the Greek word for groin). The Septuagint translation by Hebrew scholars seems more reliable than the translation to Latin by Josephus.

It is startling that in 1630 Poussin implicated rats in the pathogenesis of the bubonic plague, a fact disregarded until the end of the 19th century. Poussin lived through the Thirty Years’ War in France and Italy and might have seen cases of plague.

It was not until 1894 that Alexandre Yersin and Kitasato Shibasaburo, independently in Hong Kong isolated the bacterium responsible for the Third Bubonic Plague Pandemic. Yersin named it Pasteurella pestis after the Pasteur Institute, but in 1967 it was moved to a new genus, and renamed Yersinia pestis in honor of Yersin. Yersin also noted that rats were affected by plague during human epidemics. Plague was regarded in Asia as a disease of rats. Thus, when large numbers of rats were found dead, plague outbreaks soon followed.

Bibliography

- Butler T. Plague history: Yersin’s discovery of the causative bacterium in 1894 enabled, in the subsequent century, scientific progress in understanding the disease and the development of treatments and vaccines. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:202–9. DOIPubMed

- Freemon FR. Bubonic plague in the Book of Samuel. J R Soc Med. 2005;98:436. DOIPubMed

- Griffin JP. Bubonic plague in biblical times. J R Soc Med. 2000;93:449. DOIPubMed

- Gwilt JR. Biblical ills and remedies. J R Soc Med. 1986;79:738–41.PubMed

- Howard-Jones N. Was Shibasaburo Kitasato the co-discoverer of the plague bacillus? Perspect Biol Med. 1973;16:292–307. DOIPubMed

- Panagiotakopulu E. Fleas from Pharaonic Egypt. Antiquity. 2001;75:499–555. DOI

- Panagiotakopulu E. Pharaonic Egypt and the origin of plague. J Biogeogr. 2004;31:269–76. DOI

- Roosen J, Curtis DR. Dangers of uncritical use of historical plague data. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24:103–10. DOI

- Russell WM. Plague, rats and the Bible. J R Soc Med. 1987;80:598–9.PubMed

- Shrewsbury JF. The plague of the Philistines. J Hyg (Lond). 1949;47:244–52. DOIPubMed

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario