Strength in numbers

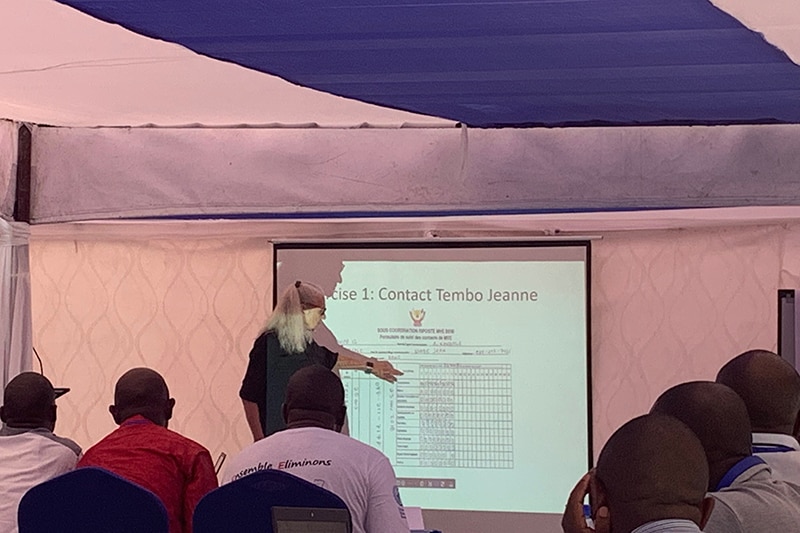

The STEER program trained healthcare workers to train others who will identify and trace contacts of people infected with the Ebola virus.

The fight against the Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) hinges not only on new treatments and vaccines but also on sharp-eyed healthcare workers in every town who are trained to quickly find new cases.

A CDC-supported program that began in July 2019 is helping build capacity by training healthcare workers to train others. The training has bolstered key skills for thousands of healthcare workers since then.

The STEER program—Surveillance Training to Enhance Ebola Response and Readiness—provides training for a network of healthcare workers in affected health zones in DRC, where Ebola has killed more than 2,000 people in three eastern provinces.

STEER was based in part on the CDC’s Field Epidemiology Training Program (FETP), which has been working to produce disease detectives or field epidemiologists in developing countries since 1980. Adapting the FETP model of formal training, field assignments, and on-the-job coaching, STEER was custom-crafted for the ongoing Ebola response.

“The best way to protect the health of the American public is by strengthening the capacity in country to contain epidemics like Ebola,” said CAPT Reina Turcios, a Public Health Service medical officer who is serving as the monitoring and evaluation specialist for STEER. “The fact is that we are only as healthy as our unhealthiest place, and the best way to prevent folks from being unhealthy is by providing appropriate training. That training is best received and strengthened coming from a peer.”

The program launched with a series of in-person sessions to boost essential outbreak control skills for health workers in the affected areas—many of them in places where the DRC’s ongoing conflicts are hindering efforts to fight the disease.

“One of the biggest challenges is that CDC staff can’t physically go to the affected areas,” said Denise Traicoff. The training and capacity development advisor for the response. To address that limitation, STEER focuses on bolstering the skills of responders already in the field, improving “a critical few things” that could help stop the outbreak.

“High-performing workers can save lives and save entire families,” Traicoff said. “The stakes could not be higher on helping them do their job well.”

STEER started with a week of training for 40 medical doctors and other senior-level healthcare providers in leadership positions. In turn, they led three-day sessions for a total of 345 healthcare workers in case detection, case reporting, and infection prevention.

The 345 people in the next phase went on to hold training sessions for a total of 1,665 healthcare workers at facilities where Ebola patients might first appear. Those healthcare workers went on to provide training in detecting and reporting suspected cases, tracing contacts, and building trust in the community for more than 5,000 community health workers who help identify new suspected cases, follow up with contacts and provide general education in towns and villages in the provinces where the outbreak has been centered.

All those sessions happened between late July and mid-August. Now the trained healthcare workers are practicing their new skills in surveillance, infection prevention and control, and community engagement to prevent Ebola transmission and stop the outbreak. Traicoff and her colleagues are watching for signs that the effort is paying off.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario