Complement system shown to remove dead cells in retinitis pigmentosa, contradicting previous research

Researchers at the National Eye Institute have found that the complement system seems to protect against retinal degeneration in retinitis pigmentosa. The research contradicts previous findings, which showed that the complement system accelerates the condition.

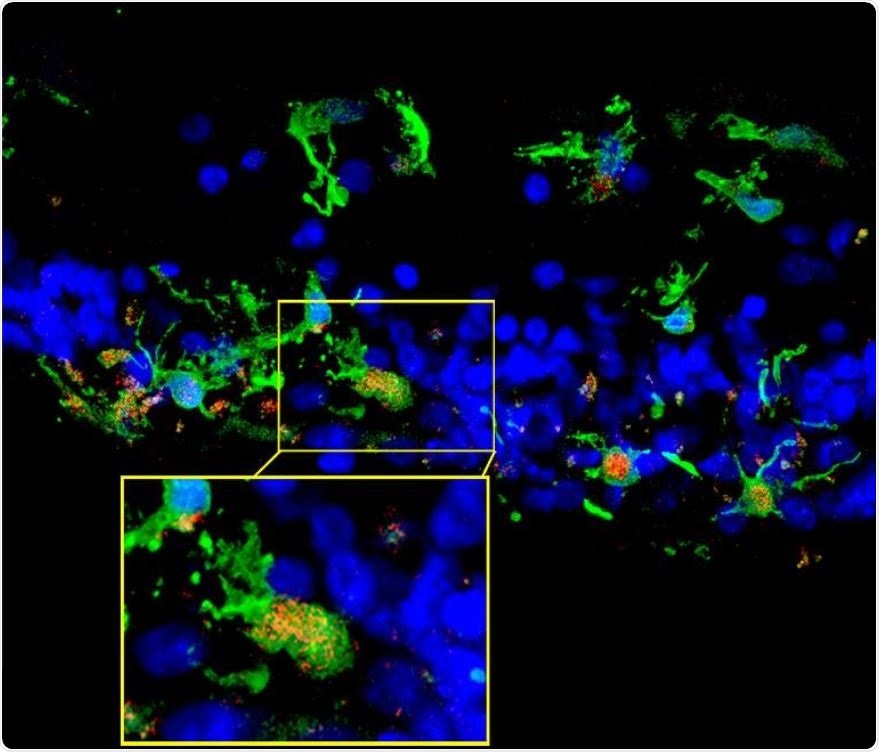

Retinal sections from a patient with retinitis pigmentosa show microglia (green) migrating into the photoreceptor layer (blue) once degeneration had begun. Inset shows microglia expressing C3 (red), which occurred in the context of photoreceptor degeneration. (Credit: NEI).

Using a mouse model of the disease, the researchers found that the activation of the complement system helped to eliminate dead cells and keep the retina in a homeostatic (physiologically balanced) state. The finding contradicts previous studies suggesting that the complement system plays a role in worsening retinal degeneration.

“Complement activation has been implicated as contributing to neurodegeneration in retinal and brain pathologies, but its role in retinitis pigmentosa, an inherited and largely incurable photoreceptor degenerative disease, is unclear,” write the authors in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

Retinitis pigmentosa is the leading cause of inherited retinal degeneration-associated blindness. It is estimated to affect around 1 in 4,000 people among all age groups and about one in three of those aged between 45 and 64 years.

What is retinitis pigmentosa?

A healthy retina is a thin, light-sensitive membrane that lines the back of the inside of the eye in vertebrates and some mollusks. This photosensitive membrane is made up of rods and cones that are stimulated by light rays and transmit impulses to the optic nerve.

In retinitis pigmentosa, changes in the pigment epithelium and damage to the retinal vasculature cause the photosensitive cells of the retina to deteriorate. Both rod and cone photoreceptors are affected, but rod photoreceptor malfunction is the most commonly encountered problem. Initially, problems begin with a loss of vision in the peripheries that cause difficulty seeing, especially in dim light. This is referred to as tunnel vision; central vision is not affected until later stages of disease progression.

There is no cure for the condition and no treatments are available that can prevent the progressive vision loss. Researchers are currently exploring potential treatments, including gene therapy and antioxidant therapies.

What has previous research shown?

Previous research has shown that activation of the complement system, which mediates inflammation, accelerates disease progression in age-related macular degeneration(AMD), which is a leading cause of blindness in people aged 65 years and older.

The role of the complement system is complex

Now, Wong and team’s study has shown that the complement system may indeed be involved in retinitis pigmentosa but may in fact worsen or curb retinal degeneration, depending on the context.

“Appreciating this complexity is important for guiding the development of therapies that target the complement immune system to treat degenerative diseases of the retina,” says Wong.

For the current study, lead author Sean Silverman and team assessed the genetic expression of the complement system in a mouse model of retinitis pigmentosa. They found that upregulation and activation of the system did indeed coincide with the degeneration of photoreceptors and that this occurred in exactly the same area that the degeneration did.

“Having found complement at the scene of the crime, we then wanted to know whether it was helping or hurting the degenerative process,” explains Wong.

Next, the team analyzed the role that a main component of the immune system – C3 – and its receptor – CR3 – may play by comparing mice with no C3 or CR3 with mice that expressed these normally.

They found that retinal degeneration was worse among the mice with genetically ablated C3 and CR3. The rod photoreceptors, which are the first cells to get destroyed in retinitis pigmentosa, were quickly lost and this was accompanied by a surge in the expression of neurotoxic inflammatory cytokines.

The C3-CR3 interaction

The researchers knew that C3 is secreted by microglia, immune cells of the central nervous system that serve as macrophages, cleaning up cellular debris in a healthy retina to maintain its function. The CR3 receptor responds to the presence of C3 by signaling to the microglia.

Once the microglia from mice with no C3 or CR3 in their retinas were placed together in a petri dish, they were found to be toxic to photoreceptors.

The findings suggest that in retinitis pigmentosa, activation of the complement system helps to clear dead cells and maintain the retina in a physiologically balanced, homeostatic state.

However, in the case of AMD, the damaging effects triggered by complement activation have led to researchers testing inhibitors of the complement system.

“Our findings suggest that this approach may be appropriate for some disease scenarios, but may induce complex responses in other disease scenarios by inhibiting helpful and homeostatic functions of inflammation,” suggests Wong.

“These homeostatic neuroinflammatory mechanisms are relevant to the design and interpretation of immunomodulatory therapeutic approaches to retinal degenerative disease,” writes the team.

More research is now needed to find out how and under which circumstances activation of the complement system may be beneficial or damaging in terms of the effect on photoreceptors and the progression of eye disease.

Source:

National Institutes of Health Press Release. June 17, 2019. Immune system can slow degenerative eye disease, NIH-led mouse study shows. nih.gov.

Journal reference:

Silverman, S. M., et al. (2019). C3- and CR3-dependent microglial clearance protects photoreceptors in retinitis pigmentosa. Journal of Experimental Medicine. DOI: 10.1084/jem.20190009.

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario