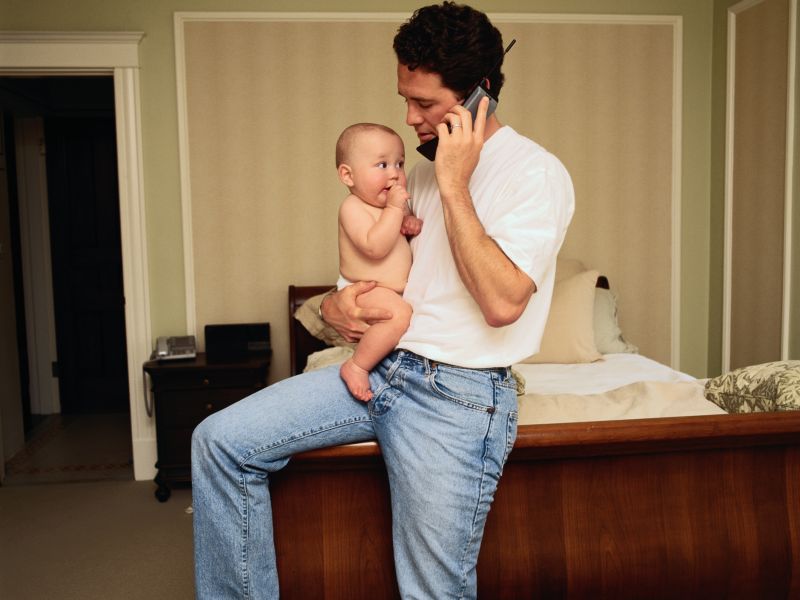

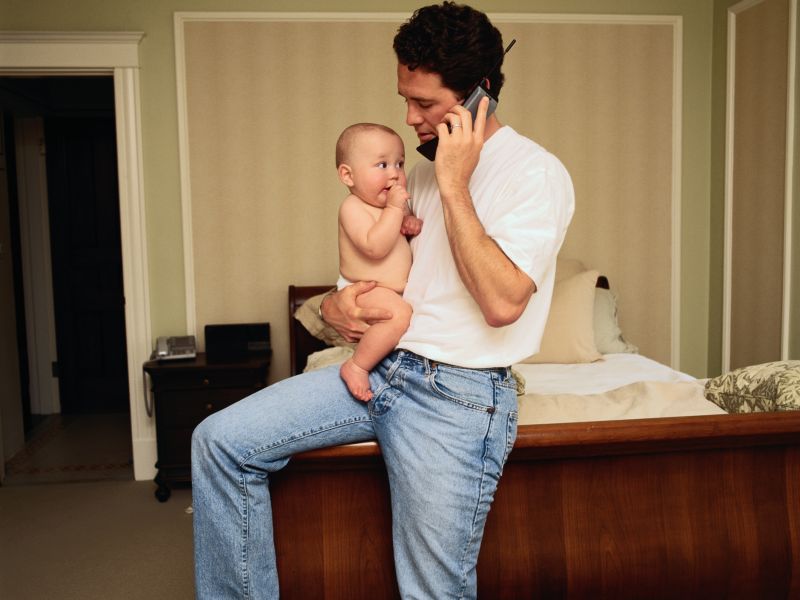

'Super Moms' and 'Super Dads': Work-Home Conflicts Affect Both Genders

'We need to bring men into the conversation,' researcher saysThursday, July 27, 2017

THURSDAY, July 27, 2017 (HealthDay News) -- Contrary to stereotypes, it's not only women who struggle to balance work and family responsibilities, according to a new report.

In a review of more than 350 studies, researchers found that, overall, men and women reported similar levels of "work-family conflicts."

That runs counter to the common belief that juggling work and family is strictly a women's issue, the researchers said.

"Both women and men are struggling with this, and we need to bring men into the conversation," said lead researcher Kristen Shockley. She's an assistant professor of psychology at the University of Georgia.

If you go by popular media, Shockley noted, it might seem that only women have to perform the work-family balancing act.

Because of that, women may be more likely to anticipate problems, Shockley said. Plus, she added, "women may be more socialized to feel that it's OK to talk about these issues."

Meanwhile, men may stay tight-lipped about their difficulties -- whether because of traditional views of men as the "bread-winner," or fear that it could undermine their career.

But an anonymous study can dig up some feelings that would otherwise stay hidden, Shockley pointed out. They ask people direct questions -- for example, whether they agree with statements like, "My work interferes with my family life more than I'd like."

Framed that way, the research review found, men and women acknowledge similar levels of work-family conflicts.

Kei Nomaguchi, an associate professor of sociology at Ohio's Bowling Green State University, said, "It's true that this is a men's issue, too."

Nomaguchi, who studies work and family issues, was not involved in the new research.

"Increasingly, men are expected to spend more time with their family, especially when they have young children," Nomaguchi said. But at the same time, she added, they can also feel pressure to fill the traditional male role of career-minded provider.

Still, the new findings do not mean that women and men have become "equal" when it comes to work and family.

Nomaguchi pointed to a key limitation of the studies Shockley's team analyzed: They surveyed people currently employed. So they missed those who'd been forced to leave their jobs because juggling work and family was too difficult.

"The women in these studies were those who'd been able to find some kind of balance between work and family," Nomaguchi said.

Shockley agreed. And beyond that, she said, the studies do not reveal how men and women were affected by their work-family conflicts.

Do women typically feel more guilt, for instance, when work interferes with family time?

Other research suggests that's the case, Nomaguchi said.

"After the baby is born, the question asked of women is, 'Are you going back to work?'" Shockley noted. "You never hear anyone ask men that question."

Plus, Nomaguchi said, women's family responsibilities often go beyond their children. They may have to care for aging parents or other family members with illnesses or disabilities.

Family income also matters. In lower-income families, Nomaguchi noted, parents often have jobs that do not provide leave or flexible work hours. This means they -- particularly moms -- may lose their job if they need time to care for family.

Higher-income jobs are more likely to offer flexibility, Nomaguchi said. But they may also require people to take work home, or constantly be "on call."

While work-family conflicts might not affect men and women in exactly the same way, it is clear that men face challenges, both researchers said.

But that's not reflected at the workplace.

According to Shockley's team, only 9 percent of U.S. workplaces offer paid paternity leave -- while nearly 22 percent provide paid maternity leave.

"It's pretty rare to find equal family leave for men and women," Shockley said.

That may be partly fueled by a belief that men do not need or want leave, she noted.

Yet the evidence suggests otherwise, Nomaguchi said. "There are many men who report work-family conflicts," she said. "And it's a good thing that this is being recognized."

The findings were published online July 27 in the Journal of Applied Psychology. They're based on 350 studies of more than 250,000 workers. Roughly half were done in the United States, while the rest were mainly from Europe and Asia.

SOURCES: Kristen Shockley, Ph.D., assistant professor, psychology, University of Georgia, Athens; Kei Nomaguchi, Ph.D., associate professor, sociology, Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, Ohio; July 27, 2017, Journal of Applied Psychology, online

HealthDay

Copyright (c) 2017 HealthDay. All rights reserved.

News stories are written and provided by HealthDay and do not reflect federal policy, the views of MedlinePlus, the National Library of Medicine, the National Institutes of Health, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- More Health News on

- Family Issues

- Occupational Health

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario