Core Elements of Hospital Antibiotic Stewardship Programs

On This Page

Introduction

Antibiotics have transformed the practice of medicine, making once lethal infections readily treatable and making other medical advances, like cancer chemotherapy and organ transplants, possible. Prompt initiation of antibiotics to treat infections reduces morbidity and save lives, for example, in cases of sepsis (1). However, about 30% of all antibiotics prescribed in U.S. acute care hospitals are either unnecessary or suboptimal (2, 3).

Like all medications, antibiotics have serious adverse effects, which occur in roughly 20% of hospitalized patients who receive them (4). Patients who are unnecessarily exposed to antibiotics are placed at risk for these adverse events with no benefit. The misuse of antibiotics has also contributed to antibiotic resistance, a serious threat to public health (5). The misuse of antibiotics can adversely impact the health of patients who are not even exposed to them through the spread of resistant organisms and Clostridioides difficile (C. difficile) (6).

For More Information

In Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019 ,CDC estimates that more than 2.8 million antibiotic-resistant infections occur in the United States each year, and more than 35,000 people die as a result.

Antibiotic Stewardship and Sepsis

There have been some misperceptions that antibiotic stewardship may hinder efforts to improve the management of sepsis in hospitals. However, rather than hindering effective patient care, antibiotic stewardship programs can play an important role in optimizing the use of antibiotics, leading to better patient outcomes.

Optimizing the use of antibiotics is critical to effectively treat infections, protect patients from harms caused by unnecessary antibiotic use, and combat antibiotic resistance. Antibiotic Stewardship Programs (ASPs) can help clinicians improve clinical outcomes and minimize harms by improving antibiotic prescribing (2, 7). Hospital antibiotic stewardship programs can increase infection cure rates while reducing (7-9):

- Treatment failures

- C. difficile infections

- Adverse effects

- Antibiotic resistance

- Hospital costs and lengths of stay

In 2014, CDC called on all hospitals in the United States to implement antibiotic stewardship programs and released the Core Elements of Hospital Antibiotic Stewardship Programs (Core Elements) to help hospitals achieve this goal. The Core Elements outlines structural and procedural components that are associated with successful stewardship programs. In 2015, The United States National Action Plan for Combating Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria set a goal for implementation of the Core Elements in all hospitals that receive federal funding (10).

Core Elements Implementation

To further support the implementation of the Core Elements, CDC has:

- Partnered with the National Quality Forum to develop the National Quality Partners Playbook: Antibiotic Stewardship in Acute Care in 2016 (11).

- Worked with the Pew Charitable Trusts, the American Hospital Association and the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy to develop an implementation guide for the Core Elements in small and critical access hospitals in 2017 (12).

Partners across the country are using the Core Elements to guide antibiotic stewardship efforts in hospital settings. The Core Elements form the foundation for antibiotic stewardship accreditation standards from the Joint Commission and DNV-GL (13). The 2019 hospital Conditions of Participation from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) created a federal regulation for hospital antibiotic stewardship programs and also reference the Core Elements (14). United States hospitals have made considerable progress implementing the Core Elements. In 2018, 85% of acute care hospitals reported having all seven of the Core Elements in place, compared to only 41% in 2014 (15).

The field of antibiotic stewardship has advanced dramatically since 2014, with much more published evidence and the release of an implementation guideline from the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (16).

Core Elements for Hospital Antibiotic Stewardship Programs: 2019

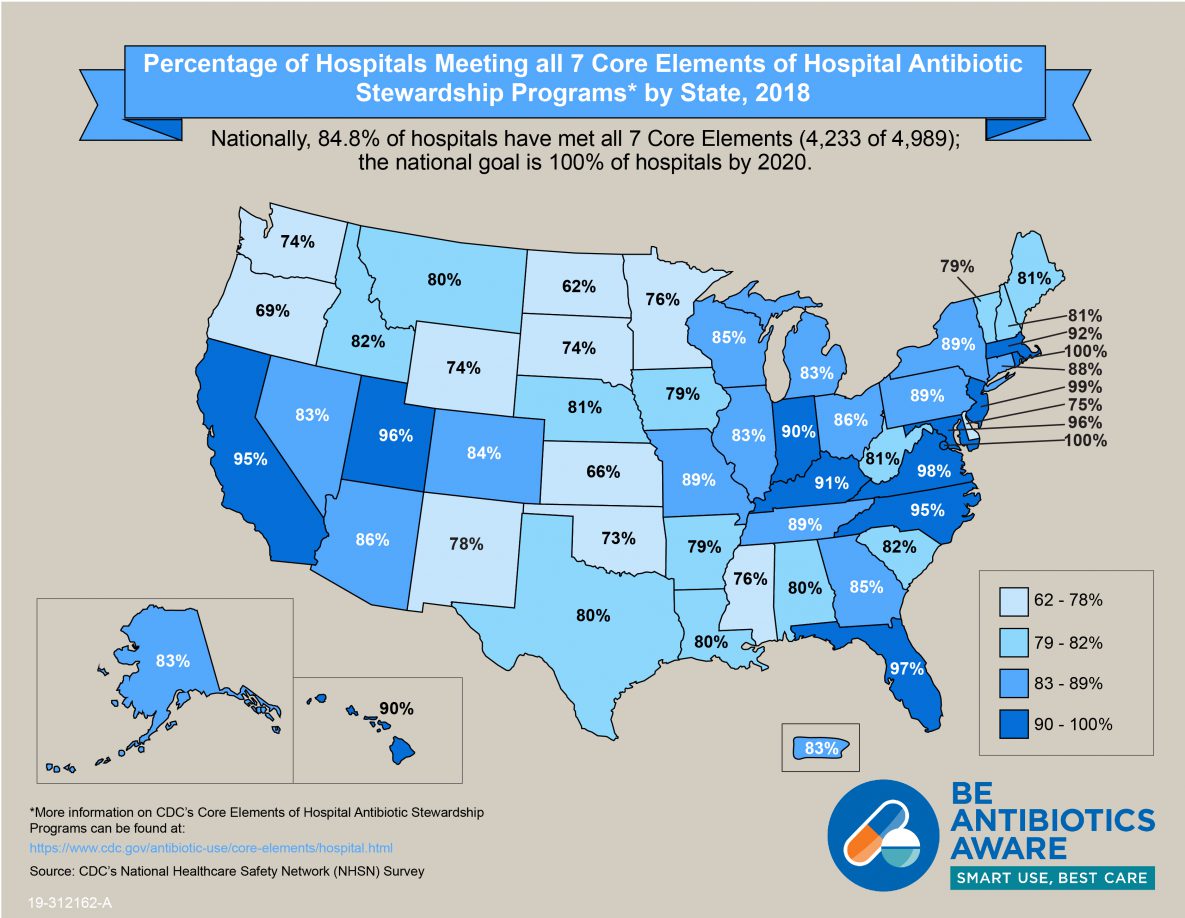

Percentage of Hospitals Meeting All 7 Core Elements by State, 2018

In 2018, 85% of acute care hospitals reported having all seven of the Core Elements in place, compared to only 41% in 2014 (15).

This document updates the 2014 Core Elements for Hospital Antibiotic Stewardship Programs and incorporates new evidence and lessons learned from experience with the Core Elements. The Core Elements are applicable in all hospitals, regardless of size. There are suggestions specific to small and critical access hospitals in Implementation of Antibiotic Stewardship Core Elements at Small and Critical Access Hospitals (12).

There is no single template for a program to optimize antibiotic prescribing in hospitals. Implementation of antibiotic stewardship programs requires flexibility due to the complexity of medical decision-making surrounding antibiotic use and the variability in the size and types of care among U.S. hospitals. In some sections, CDC has identified priorities for implementation, based on the experiences of successful stewardship programs and published data. The Core Elements are intended to be an adaptable framework that hospitals can use to guide efforts to improve antibiotic prescribing. The assessment tool that accompanies this document can help hospitals identify gaps to address.

Summary of Updates to the Core Elements of Hospital Antibiotic Stewardship Programs

Optimizing the use of antibiotics is critical to effectively treat infections, protect patients from harms caused by unnecessary antibiotic use, and combat antibiotic resistance. Antibiotic stewardship programs can help clinicians improve clinical outcomes and minimize harms by improving antibiotic prescribing.

In 2019, CDC updated the hospital Core Elements to reflect both lessons learned from five years of experience as well as new evidence from the field of antibiotic stewardship. Major updates to the hospital Core Elements include:

Hospital Leadership Commitment: Dedicate necessary human, financial and information technology resources.

- The 2019 update has additional examples of hospital leadership, and the examples are stratified by “priority” and “other”.

- Priority examples of hospital leadership commitment emphasize the necessity of antibiotic stewardship programs leadership having dedicated time and resources to operate the program effectively, along with ensuring that program leadership has regularly scheduled opportunities to report stewardship activities, resources and outcomes to senior executives and hospital board.

Accountability: Appoint a leader or co-leaders, such as a physician and pharmacist, responsible for program management and outcomes.

- The 2019 update highlights the effectiveness of the physician and pharmacy co-leadership, which was reported by 59% of the hospitals responding to the 2019 NHSN Annual Hospital Survey.

Pharmacy Expertise (previously “Drug Expertise”): Appoint a pharmacist, ideally as the co-leader of the stewardship program, to lead implementation efforts to improve antibiotic use.

- This Core Element was renamed “Pharmacy Expertise” to reflect the importance of pharmacy engagement for leading implementation efforts to improve antibiotic use.

Action: Implement interventions, such as prospective audit and feedback or preauthorization, to improve antibiotic use.

- The 2019 update has additional examples of interventions which are stratified to “priority” and “other”. The “other” interventions are categorized as infection-based, provider-based, pharmacy-based, microbiology-based, and nursing-based interventions.

- Priority interventions include prospective audit and feedback, preauthorization, and facility-specific treatment recommendations. Evidence demonstrates that prospective audit and feedback and preauthorization improve antibiotic use and are recommended in guidelines as “core components of any stewardship program”. Facility-specific treatment guidelines can be important in enhancing the effectiveness of prospective audit and feedback and preauthorization.

- The 2019 update emphasizes the importance of actions focused on the most common indications for hospital antibiotic use: lower respiratory tract infection (e.g., community-acquired pneumonia), urinary tract infection, and skin and soft tissue infection.

- The antibiotic timeout has been reframed as a useful supplemental intervention, but it should not be a substitute for prospective audit and feedback.

- A new category of nursing-based actions was added to reflect the important role that nurses can play in hospital antibiotic stewardship efforts.

Tracking: Monitor antibiotic prescribing, impact of interventions, and other important outcomes like C. difficile infection and resistance patterns.

- It is important for hospitals to electronically submit antibiotic use data to the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) Antimicrobial Use (AU) Option for monitoring and benchmarking inpatient antibiotic use.

- Antibiotic stewardship process measures were expanded and stratified into “priority” and “other”.

- Priority process measures emphasize assessing the impact of the key interventions, including prospective audit and feedback, preauthorization, and facility-specific treatment recommendations.

Reporting: Regularly report information on antibiotic use and resistance to prescribers, pharmacists, nurses, and hospital leadership.

- The 2019 update points out the effectiveness of provider level data reporting, while acknowledging that this has not been well studied for hospital antibiotic use.

Education: Educate prescribers, pharmacists, and nurses about adverse reactions from antibiotics, antibiotic resistance and optimal prescribing.

- The 2019 update highlights that case-based education through prospective audit and feedback and preauthorization are effective methods to provide education on antibiotic use. This can be especially powerful when the case-based education is provided in person (e.g., handshake stewardship).

- The 2019 update also suggests engaging nurses in patient education efforts.

CDC Efforts to Support Antibiotic Stewardship

The Core Elements of Hospital Antibiotic Stewardship Programs is one of a suite of documents intended to help improve the use of antibiotics across the spectrum of health care. Building upon the hospital Core Elements framework, CDC also developed guides for other healthcare settings:

- The Core Elements of Antibiotic Stewardship for Nursing Homes

- Core Elements of Outpatient Antibiotic Stewardship

- Core Elements of Human Antibiotic Stewardship Programs in Resource Limited Settings

CDC has also published an implementation guide for the Core Elements in small and critical access hospitals, Implementation of Antibiotic Stewardship Core Elements in Small and Critical Access Hospitals (12).

CDC will continue to use a variety of data sources, including the NHSN annual survey of hospital stewardship practices and AU Option, to find ways to optimize hospital antibiotic stewardship programs and practices. CDC will also continue to collaborate with an array of partners who share a common goal of improving antibiotic use.

With stewardship programs now in place in most US hospitals, the focus is on optimizing these programs. CDC recognizes that research is essential to discover both more effective ways to implement proven stewardship practices as well as new approaches. CDC will continue to support research efforts aimed at finding innovative solutions to stewardship challenges.

References

- Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, Levy MM, Antonelli M, Ferrer R, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2016. Intensive care medicine. 2017 Mar;43(3):304-77.

- Dellit TH, Owens RC, McGowan JE, Jr., Gerding DN, Weinstein RA, Burke JP, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America guidelines for developing an institutional program to enhance antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2007 Jan 15;44(2):159-77.

- Fridkin SK, Baggs J., Fagan R., Magill S., Pollack L.A., Malpiedi P., Slayton R. Vital Signs: Improving Antibiotic Use Among Hospitalized Patients. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(9):194-200.

- Tamma PD, Avdic E, Li DX, Dzintars K, Cosgrove SE. Association of Adverse Events With Antibiotic Use in Hospitalized Patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Sep 1;177(9):1308-15.

- Huttner A, Harbarth S, Carlet J, Cosgrove S, Goossens H, Holmes A, et al. Antimicrobial resistance: a global view from the 2013 World Healthcare-Associated Infections Forum. Antimicrobial resistance and infection control. 2013 Nov 18;2(1):31.

- Brown K, Valenta K, Fisman D, Simor A, Daneman N. Hospital ward antibiotic prescribing and the risks of Clostridium difficile infection. JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Apr;175(4):626-33.

- Davey P, Marwick CA, Scott CL, Charani E, McNeil K, Brown E, et al. Interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing practices for hospital inpatients. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2017 Feb 9;2:Cd003543.

- Karanika S, Paudel S, Grigoras C, Kalbasi A, Mylonakis E. Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Clinical and Economic Outcomes from the Implementation of Hospital-Based Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2016 Aug;60(8):4840-52.

- Baur D, Gladstone BP, Burkert F, Carrara E, Foschi F, Dobele S, et al. Effect of antibiotic stewardship on the incidence of infection and colonisation with antibiotic-resistant bacteria and Clostridium difficile infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Infectious diseases. 2017 Sep;17(9):990-1001.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U.S. National Action Plan for Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria (National Action Plan). Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/us-activities/national-action-plan.html

- National Quality Forum. National Quality Partners Playbook: Antibiotic Stewardship in Acute Care. Available from: http://www.qualityforum.org/NQP/Antibiotic_Stewardship_Playbook.aspx

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Implementation of Antibiotic Stewardship Core Elements at Small and Critical Access Hospitals. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/core-elements/small-critical.html

- DNV-GL. NATIONAL INTEGRATED ACCREDITATION FOR HEALTHCARE ORGANIZATIONS (NIAHO®) DNV [PDF – 238 pages]. Available from: http://bit.ly/DNVGLNIAHOAcute#page=150

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Regulatory Provisions To Promote Program Efficiency, Transparency, and Burden Reduction; Fire Safety Requirements for Certain Dialysis Facilities; Hospital and Critical Access Hospital (CAH) Changes To Promote Innovation, Flexibility, and Improvement in Patient Care. Available from: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/09/30/2019-20736/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-regulatory-provisions-to-promote-program-efficiency-transparency-and

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Patient Safety Portal. Available from: https://arpsp.cdc.gov/

- Barlam TF, Cosgrove SE, Abbo LM, MacDougall C, Schuetz AN, Septimus EJ, et al. Implementing an Antibiotic Stewardship Program: Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016 May 15;62(10):e51-77.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario