03/28/2017 09:00 AM EDT

Stem cells derived from a person’s own body have the potential to replace tissue damaged by a wide array of diseases. Now, two reports published in the New England Journal of Medicine highlight the promise—and the peril—of this rapidly advancing area of regenerative medicine. Both groups took aim at the same disorder: age-related macular degeneration […]

Blog Info

Regenerative Medicine: The Promise and Peril

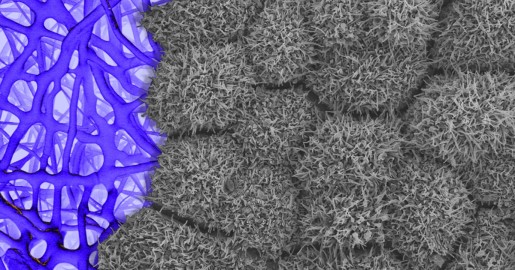

Caption: Scanning electron micrograph of iPSC-derived retinal pigment epithelial cells growing on a nanofiber scaffold (blue).

Credit: Sheldon Miller, Arvydas Maminishkis, Robert Fariss, and Kapil Bharti, National Eye Institute/NIH

Credit: Sheldon Miller, Arvydas Maminishkis, Robert Fariss, and Kapil Bharti, National Eye Institute/NIH

Stem cells derived from a person’s own body have the potential to replace tissue damaged by a wide array of diseases. Now, two reports published in the New England Journal of Medicine highlight the promise—and the peril—of this rapidly advancing area of regenerative medicine. Both groups took aim at the same disorder: age-related macular degeneration (AMD), a common, progressive form of vision loss. Unfortunately for several patients, the results couldn’t have been more different.

In the first case, researchers in Japan took cells from the skin of a female volunteer with AMD and used them to create induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) in the lab. Those iPSCs were coaxed into differentiating into cells that closely resemble those found near the macula, a tiny area in the center of the eye’s retina that is damaged in AMD. The lab-grown tissue, made of retinal pigment epithelial cells, was then transplanted into one of the woman’s eyes. While there was hope that there might be actual visual improvement, the main goal of this first in human clinical research project was to assess safety. The patient’s vision remained stable in the treated eye, no adverse events occurred, and the transplanted cells remained viable for more than a year.

Exciting stuff, but, as the second report shows, it is imperative that all human tests of regenerative approaches be designed and carried out with the utmost care and scientific rigor. In that instance, three elderly women with AMD each paid $5,000 to a Florida clinic to be injected in both eyes with a slurry of cells, including stem cells isolated from their own abdominal fat. The sad result? All of the women suffered severe and irreversible vision loss that left them legally or, in one case, completely blind.

AMD starts out as the “dry” form, with its characteristic thinning and loss of tissue in the macula. Over the years, that can erode a person’s central vision, which is important for reading and other similar tasks. Some people will also eventually develop the more-destructive “wet” form, in which new blood vessels begin growing near the macula.

Because these blood vessels are unstable, they leak blood and other fluids that can destroy vision more rapidly. While treatments exist to seal the leaky blood vessels or prevent their growth, there’s no proven way to restore lost vision in a person with AMD.

The Japanese study involved Shinya Yamanaka, a co-recipient of the 2012 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine for discovering iPSCs, and Masayo Takahashi from Kyoto University [1]. In the study, the researchers and their colleagues took cells from the skin of a 77-year-old Japanese woman with wet AMD and produced iPSCs. They then used the iPSCs to grow a sheet of retinal pigment epithelial cells in the lab.

In September 2014, they grafted the tissue into the retina of her right eye—and it integrated into a layer of pigmented retinal cells and became functioning tissue. What’s more, because the transplant was made from her own body, the woman didn’t need to take an immunosuppressant. A year later, the transplanted tissue remained fully intact. While the woman’s vision in the treated eye hadn’t improved, it had stabilized.

For safety reasons, the researchers had intentionally selected the woman as their first patient because her vision was already severely compromised. With other parts of her retina already damaged, it was unlikely the iPSC treatment would improve her vision. But the success of this first surgery is nevertheless an important and promising step in demonstrating the safety of iPSC-derived tissue transplantation.

It’s worth noting that the Japanese team also produced replacement tissue from the cells of a 68-year-old Japanese man with wet AMD. However, the researchers later detected subtle genetic changes in his iPSCs and decided not to go through with the surgery, again for safety reasons.

In the second report, NIH-funded researchers detail the tragic cases of three elderly women with dry AMD who received another type of experimental treatment at a Florida clinic [2]. The researchers, who were not affiliated with the clinic, became aware of the situation after the women sought treatment at their university-based ophthalmology practices. As the researchers report, each of the patients who’d undergone the experimental treatment were suffering from a range of serious eye problems, including increased intraocular pressure, bleeding, and retinal detachment.

The women all recounted a similar story. They learned about what they believed to be a clinical trial of an experimental treatment. The treatment, as they were told subsequently, cost $5,000 and involved liposuction to remove a sample of fat tissue. That tissue was then processed to isolate putative stem cells. These cells were suspended in a solution produced from each patient’s own blood and immediately injected into both eyes. The women were told afterwards to use antibiotic drops and to limit their activities for three days. Within a week, all had severe vision loss.

As others have noted, the experience of these women included several major red flags. For one thing, people participating in clinical trials shouldn’t be asked to pay for their treatment. Secondly, although the women thought they were participating in clinical trial, they were handed written consent forms that made no mention of research. Finally, in a properly designed clinical trial for an experimental eye treatment, you would never treat both eyes at once!

As for Takahashi and Yamanaka, while they demonstrated their approach in a patient with wet AMD, the more prevalent form in Japan, in principle they say such a treatment could benefit people with either form of the disease. The researchers report that they are now pursuing surgeries with iPSCs produced from another person’s blood cells instead of a patient’s own cells. Despite the increased chances for rejection, such approaches might prove more practical. They wouldn’t require iPSC production for each and every patient, which is time-consuming and expensive.

The future for regenerative medicine in AMD surely does look bright. At the same time, the juxtaposition of these two reports serves as an important cautionary tale. As promising as regenerative medicine is, we must take care not to let ourselves get out ahead of the evidence. “First do no harm” has to be our watchword.

References:

[1] Vision Loss after Intravitreal Injection of Autologous “Stem Cells” for AMD.Kuriyan AE, Albini TA, Townsend JH, Rodriguez M, Pandya HK, Leonard RE 2nd, Parrott MB, Rosenfeld PJ, Flynn HW Jr, Goldberg JL. N Engl J Med. 2017 Mar 16;376(11):1047-1053.

[2] Autologous Induced Stem-Cell-Derived Retinal Cells for Macular Degeneration. Mandai M, Watanabe A, Kurimoto Y, Hirami Y, Morinaga C, Daimon T, Fujihara M, Akimaru H, Sakai N, Shibata Y, Terada M, Nomiya Y, Tanishima S, Nakamura M, Kamao H, Sugita S, Onishi A, Ito T, Fujita K, Kawamata S, Go MJ, Shinohara C, Hata KI, Sawada M, Yamamoto M, Ohta S, Ohara Y, Yoshida K, Kuwahara J, Kitano Y, Amano N, Umekage M, Kitaoka F, Tanaka A, Okada C, Takasu N, Ogawa S, Yamanaka S, Takahashi M. N Engl J Med. 2017 Mar 16;376(11):1038-1046.

Links:

Facts about Age-Related Macular Degeneration (National Eye Institute/NIH)

Nine Things to Know about Stem Cell Treatments (International Society for Stem Cell Research)

Shinya Yamanaka (Kyoto University, Japan)

Masayo Takahaski (Kyoto University, Japan)

NIH Support: National Eye Institute

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario