|

| MMWR Weekly Vol. 65, No. 40 October 14, 2016 |

| PDF of this issue |

Patterns and Trends in Age-Specific Black-White Differences in Breast Cancer Incidence and Mortality – United States, 1999–2014

Weekly / October 14, 2016 / 65(40);1093–1098

Lisa C. Richardson, MD1; S. Jane Henley, MSPH1; Jacqueline W. Miller, MD1; Greta Massetti, PhD1; Cheryll C. Thomas, MSPH1 (View author affiliations)

View suggested citationSummary

What is already known about this topic?Despite improvements in early detection and treatment for breast cancer, black women continue to have the highest breast cancer mortality rate. Since 1975, black women have had lower breast cancer incidence compared to white women, but rates have recently converged, in part because of increasing breast cancer incidence in black women.

What is added by this report?In-depth analyses of population-based data indicated that breast cancer incidence is equal for black and white women in part because of incidence increasing among black women, particularly among those aged 60–79 years. Breast cancer mortality continues to be higher among black women compared with white women, with death rates decreasing faster among white women. However, among women aged <50 years, breast cancer death rates are decreasing at the same rate among black and white women.

What are the implications for public health practice?Measures to ensure access to quality care and the best-available treatments for all women diagnosed with breast cancer can help address these racial disparities. Increasing trends in obesity prevalence among black women could be contributing to increasing incidence of breast cancer. Thus, increasing and sustaining public health interventions to increase physical activity and promote a healthy diet to reach and maintain a healthy weight throughout a woman’s life need to be considered. As tailored interventions and therapies are developed and implemented, public health professionals can use population-based incidence and mortality data to monitor their impact on health disparities.

Lisa C. Richardson, MD1; S. Jane Henley, MSPH1; Jacqueline W. Miller, MD1; Greta Massetti, PhD1; Cheryll C. Thomas, MSPH1 (View author affiliations)

View suggested citationBreast cancer continues to be the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the second leading cause of cancer deaths among U.S. women (1). Compared with white women, black women historically have had lower rates of breast cancer incidence and, beginning in the 1980s, higher death rates (1). This report examines age-specific black-white disparities in breast cancer incidence during 1999–2013 and mortality during 2000–2014 in the United States using data from United States Cancer Statistics (USCS) (2). Overall rates of breast cancer incidence were similar, but death rates remained higher for black women compared with white women. During 1999–2013, breast cancer incidence decreased among white women but increased slightly among black women resulting in a similar average incidence at the end of the period. Breast cancer incidence trends differed by race and age, particularly from 1999 to 2004–2005, when rates decreased only among white women aged ≥50 years. Breast cancer death rates decreased significantly during 2000–2014, regardless of age with patterns varying by race. For women aged ≥50 years, death rates declined significantly faster among white women compared with black women; among women aged <50 years, breast cancer death rates decreased at the same rate among black and white women. Although some of molecular factors that lead to more aggressive breast cancer are known, a fuller understanding of the exact mechanisms might lead to more tailored interventions that could decrease mortality disparities. When combined with population-based approaches to increase knowledge of family history of cancer, increase physical activity, promote a healthy diet to maintain a healthy bodyweight, and increase screening for breast cancer, targeted treatment interventions could reduce racial disparities in breast cancer.

USCS includes incidence data from CDC’s National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR) and the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program and mortality data from the National Vital Statistics System (2). Data on new cases of invasive (malignant) breast cancer* diagnosed during 1999–2013 were obtained from population-based cancer registries affiliated with NPCR or SEER programs in each state and the District of Columbia (DC). Incidence data in this report met USCS publication criteria, covering 99% of the U.S. population during 2009–2013 and 92% during 1999–2013.† SEER Summary Stage 2000§ was used to characterize cancers as localized, regional, distant, or unknown stage using clinical and pathologic tumor characteristics, such as tumor size, depth of invasion and extension to regional or distant tissues, involvement of regional lymph nodes, and distant metastases. Breast cancer death data during 2000–2014 were based on death certificate information reported to state vital statistics offices and compiled into a national file through the National Vital Statistics System; mortality data in this report cover 100% of the U.S. population. Race and ethnicity were abstracted from medical records for cases and from death certificates for deaths; this report includes all races, white, and black, regardless of ethnicity. Population estimates for the denominators of incidence and death rates were from the U.S. Census, as modified by the National Cancer Institute. Five-year average annual incidence rates for 2009–2013 and death rates for 2010–2014 per 100,000 women were age-adjusted by the direct method to the 2000 U.S. standard population (19 age groups).¶ Average annual percentage change was used to quantify changes in incidence rates during 1999–2013 and death rates during 2000–2014 and was calculated using joinpoint regression, which allowed different slopes for three periods; the year at which slopes changed could vary by race and age.

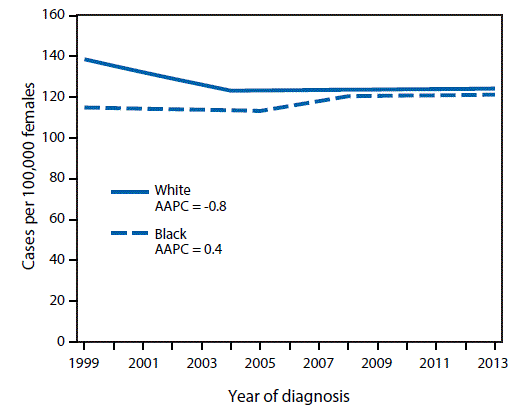

During 2009–2013, approximately 221,000 breast cancers were diagnosed each year (Table). Overall incidence of breast cancer was similar among black women (121.5 cases per 100,000 population) and white women (123.6 cases per 100,000 population), but differences by age and stage were found. Compared with white women, breast cancer incidence was higher among black women aged <60 years, but lower among black women aged ≥60 years. Black women had a lower percentage of breast cancers diagnosed at a localized stage (54%) than did white women (64%) (Table). Among white women, breast cancer incidence decreased from 1999 to 2004, and then stabilized, decreasing 0.8% per year on average; however, breast cancer incidence was stable from 1999 to 2005 among black women and then nonsignificantly increased (Figure 1). Breast cancer incidence trends differed by race and age, particularly during 1999–2004 when rates decreased only among white women aged ≥50 years. During 1999–2013, among women aged 60–79 years, rates of breast cancer incidence decreased significantly among white women, but increased significantly among black women (https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/statistics/trends_invasive.htm).

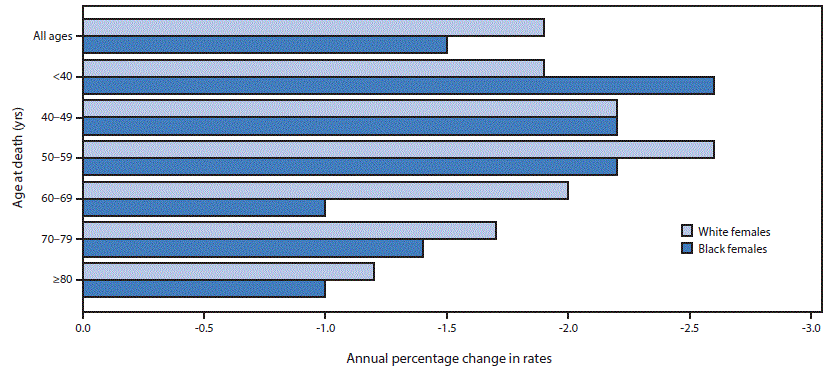

During 2010–2014, approximately 41,000 deaths from breast cancer occurred each year (Table). Breast cancer mortality was 41% higher among black women (29.2 deaths per 100,000 population) than white women (20.6 deaths per 100,000 population). Breast cancer death rates decreased during 2010–2014 among both blacks and whites, although differences in trends by race and age were found (Figure 2). Overall, breast cancer death rates decreased faster among white women (−1.9% per year) compared with black women (−1.5% per year). Among women aged <50 years, breast cancer death rates decreased at the same pace among black and white women, whereas white women aged ≥50 years had significantly larger decreases. The largest difference by race was observed among women aged 60–69 years: breast cancer death rates decreased 2.0% per year among white women compared with 1.0% among black women.

Discussion

Recent trends in breast cancer incidence suggest that the convergence and now equal incidence for black and white women has been primarily because of incidence increasing among black women, particularly among those aged 60–79 years, and concomitant decreasing or stable rates in white women. Breast cancer mortality is approximately 40% higher among black women compared with white women, with faster decreases in mortality among white women. This report confirms previous findings by race overall (1), and presents age-specific changes for incidence and mortality by race.

A previous CDC report suggested that improvements in follow-up of abnormal screening tests and treatment for breast cancer for black women could address racial disparities (3). Several recent large-scale federal initiatives have provided a novel opportunity to address racial disparities in breast cancer subtypes and beyond at the molecular level. Advances in understanding breast cancer subtypes have improved awareness that black women are more likely to be diagnosed with triple negative breast cancer (negative estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and HER2 status), which might have improved the likelihood that they receive the appropriate treatment based on their cancer type (4). The Precision Medicine Initiative** promotes advances in research, technology, and policies to enable researchers, providers and patients to work together to develop individualized care by understanding how the molecular characteristics of cancers lead to phenotypic characteristics noted in the clinical setting. The Cancer Moonshot†† is focused on addressing the most pressing needs for cancer control, including accelerating the understanding of cancer and its prevention, early detection, treatment, and cure. Both initiatives are focused on determining the genetic variations that increase risk for aggressive breast cancer so that tailored interventions and treatment plans can be developed.

Long-term breast cancer incidence trends for black women indicate steady increases over the past 40 years, resulting in incidence rates equivalent to those among white women in 2013 (5). In-depth analyses by age, race, and period of diagnosis indicate that the largest increases are seen among black women aged 60–79 years. The reason for this temporal trend in black women is not well understood. The increasing breast cancer incidence suggests there might be a screening effect from increased use of mammography (6). Previous increasing trends in obesity prevalence among black women might also play a role (7). The exact biologic mechanisms for the association between obesity and increased risk for breast cancer are still unknown (7). These increasing trends might stabilize and decline by sustaining and increasing public health interventions to increase physical activity and promote a healthy diet to reach and maintain a healthy weight throughout a woman’s life (7). Much of the decrease in breast cancer incidence among white women is believed to be because of decreased use of postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy based on findings from the Women’s Health Initiative (1).

This report illustrates that the disparity in breast cancer mortality is stable, with comparable declines in death rates among younger black and white women. Previous studies have indicated that similar use of mammography screening among black and white women has led to more cancers being diagnosed at an early stage, and more appropriate treatment of aggressive cancers in young black women (4,8). At the population level, some communities have demonstrated success in achieving equity for black women dying from breast cancer; these successes provide opportunities to learn about pathways for improved outcomes (9).

The findings in this report are subject to at least three limitations. First, race and ethnicity data were ascertained from medical records and death certificates and might be subject to misclassification; however, misclassification is minimal for black and white race (10). Second, the most recent data are several years old, because current requirements for reporting cancer registry data are rigorous and require multiple steps. Finally, cancer registries do not routinely collect risk factor information that could inform the trends noted here.

Breast cancer mortality is decreasing for both black and white women, with equal pace of decrease for younger black and white women. Continued decreases involve accelerating current progress and understanding breast cancer genomics for predicting risk and promoting effective treatment through new initiatives like the Precision Medicine Initiative and Cancer Moonshot. Public health professionals need to work in tandem with scientists and clinical researchers to monitor the successes of these newly developed therapies by assessing disparities at a population level using trends in incidence and death rates.

Corresponding author: Lisa C. Richardson, lrichardson@cdc.gov, 770-488-0170.

1Division of Cancer Prevention and Control, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC.

References

- DeSantis CE, Fedewa SA, Goding Sauer A, Kramer JL, Smith RA, Jemal A. Breast cancer statistics, 2015: convergence of incidence rates between black and white women. CA Cancer J Clin 2016;66:31–42. CrossRef PubMed

- US Cancer Statistics Working Group. United States cancer statistics: 1999–2013 incidence and mortality web-based report. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; National Cancer Institute; 2016. https://nccd.cdc.gov/uscs/

- CDC. Vital signs: racial disparities in breast cancer severity—United States, 2005–2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012;61:922–6. PubMed

- Keenan T, Moy B, Mroz EA, et al. Comparison of the genomic landscape between primary breast cancer in African American versus white women and the association of racial differences with tumor recurrence. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:3621–7. CrossRef PubMed

- Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. , eds. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2013. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2016. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2013

- Grabler P, Dupuy D, Rai J, Bernstein S, Ansell D. Regular screening mammography before the diagnosis of breast cancer reduces black:white breast cancer differences and modifies negative biological prognostic factors. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012;135:549–53. CrossRef PubMed

- Bandera EV, Maskarinec G, Romieu I, John EM. Racial and ethnic disparities in the impact of obesity on breast cancer risk and survival: a global perspective. Adv Nutr 2015;6:803–19.CrossRef PubMed

- Toriola AT, Colditz GA. Trends in breast cancer incidence and mortality in the United States: implications for prevention. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2013;138:665–73. CrossRef PubMed

- Rust G, Zhang S, Malhotra K, et al. Paths to health equity: local area variation in progress toward eliminating breast cancer mortality disparities, 1990–2009. Cancer 2015;121:2765–74.CrossRef PubMed

- Arias E, Heron M, Hakes JK. The validity of race and Hispanic-origin reporting on death certificates in the United States: an update. Vital and Health Statistics, series 2, no. 172. Atlanta, GA: CDC, National Center for Health Statistics; 2016. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_02/sr02_172.pdf

* Cases were classified by anatomic site using the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O), Third Edition (http://codes.iarc.fr/).

† Cancer registries demonstrated that cancer incidence data were of high quality by meeting the six USCS publication criteria: 1) case ascertainment ≥90% complete; 2) ≤5% of cases ascertained solely on the basis of death certificate; 3) ≤3% of cases missing information on sex; 4) ≤3% of cases missing information on age; 5) ≤5% of cases missing information on race; and 6) ≥97% of registry’s records passed a set of single-field and inter-field computerized edits that test the validity and logic of data components. Additional information available at https://nccd.cdc.gov/uscs/.

¶ Population estimates incorporate bridged single-race estimates derived from the original multiple race categories in the 2010 U.S. Census. http://seer.cancer.gov/popdata/ and https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/bridged_race.htm.

Source: CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics National Vital Statistics System, National Program of Cancer Registries and the National Cancer Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program.

Abbreviation: CI = confidence interval.

* Rates are per 100,000 persons and age-adjusted to the 2000 U.S. Standard population (19 age groups-Census P25–1130); 95% CIs were calculated as modified gamma intervals.

† Incidence data are compiled from cancer registries that meet the data quality criteria for all invasive cancer sites combined for all years 2009–2013 (covering approximately 99% of the U.S. population). Registry-specific data quality information is available at https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/npcr/uscs/data/00_data_quality.htm. Mortality data cover 100% of the U.S. population.

§ A localized cancer is one that is confined to the primary site, a regional cancer is one that has spread directly beyond the primary site or to regional lymph nodes, and a distant cancer is one that has spread to other organs. Percentages of stages do not sum to 100% because data for cases with unknown stage are not presented. To use the most accurate staging information, this report excludes cases that were identified by autopsy or death certificate only.

¶ Rates among black women were significantly (p<0.05) different than among white women in all comparisons except overall incidence among women aged 40–49 years.

Abbreviation: CI = confidence interval.

* Rates are per 100,000 persons and age-adjusted to the 2000 U.S. Standard population (19 age groups-Census P25–1130); 95% CIs were calculated as modified gamma intervals.

† Incidence data are compiled from cancer registries that meet the data quality criteria for all invasive cancer sites combined for all years 2009–2013 (covering approximately 99% of the U.S. population). Registry-specific data quality information is available at https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/npcr/uscs/data/00_data_quality.htm. Mortality data cover 100% of the U.S. population.

§ A localized cancer is one that is confined to the primary site, a regional cancer is one that has spread directly beyond the primary site or to regional lymph nodes, and a distant cancer is one that has spread to other organs. Percentages of stages do not sum to 100% because data for cases with unknown stage are not presented. To use the most accurate staging information, this report excludes cases that were identified by autopsy or death certificate only.

¶ Rates among black women were significantly (p<0.05) different than among white women in all comparisons except overall incidence among women aged 40–49 years.

FIGURE 1. Trends* in invasive female breast cancer incidence, by race† and year of diagnosis — United States,§ 1999–2013

FIGURE 1. Trends* in invasive female breast cancer incidence, by race† and year of diagnosis — United States,§ 1999–2013

Source: CDC’s National Program of Cancer Registries and the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program.

Abbreviation: AAPC=Average annual percentage change

* Trends were measured with AAPC in rates, calculated using joinpoint regression, which allowed different slopes for three periods; the year at which slopes changed could vary by age and sex.

† AAPC for white females was significantly different (p<0.05) than zero. Trend among black women was significantly different (p<0.05) than among white women.

§ Data are compiled from cancer registries that meet the data quality criteria for all invasive cancer sites combined for all years during 1999–2013 (covering approximately 92% of the U.S. population). Registry-specific data quality information is available at https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/npcr/uscs/data/00_data_quality.htm.

FIGURE 2. Average annual percentage change* in female breast cancer death rates, by age group and race† — United States, 2000–2014

FIGURE 2. Average annual percentage change* in female breast cancer death rates, by age group and race† — United States, 2000–2014

Source: CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics National Vital Statistics System.

Abbreviation: AAPC = average annual percentage change.

* AAPC was calculated using joinpoint regression, which allowed different slopes for three periods; the year at which slopes changed could vary by age and race. All AAPCs were significantly different (p<0.05) than zero.

† Trends among black women were significantly different (p<0.05) than among white women for the following age groups: all ages, 50–59 years, 60–69 years, and 79–79 years.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario