Aiming to Prevent Hereditary Cancers, Researchers Focus on Lynch Syndrome

A working group of the Cancer MoonshotSM Blue Ribbon Panel recommended in 2016 that NCI launch projects to demonstrate how screening and early detection could reduce the burden of cancer among individuals at high risk of developing the disease.

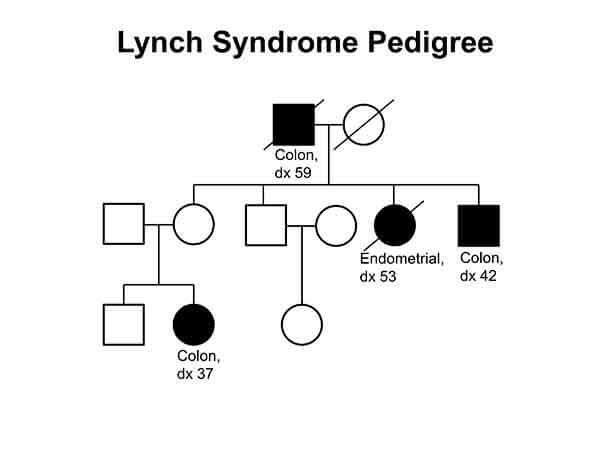

The Blue Ribbon Panel identified two main areas of focus for the research: Lynch syndromeand hereditary breast and ovarian syndrome. Lynch syndrome is an inherited condition that increases the risk of developing colorectal and endometrial cancers—often before age 50—as well as certain other types of cancer, including stomach, ovarian, small intestine, and brain.

Studying hereditary cancers such as Lynch syndrome can help researchers learn about how to prevent cancers, the Blue Ribbon Panel noted. Because hereditary cancers tend to progress from precancerous stages to cancer more rapidly than non-inherited forms of the disease, researchers may gain insights into the biology of cancer in shorter periods of time.

And individuals who are diagnosed with hereditary cancers may be able to reduce the risk of developing certain cancers through strategies such as regular colonoscopy in the case of Lynch syndrome. They may also be able to join short-term cancer prevention clinical trials, which can help researchers develop new strategies for the prevention and early detection of cancer.

In pilot studies, screening healthy members of families with Lynch syndrome for colorectal cancer led to a 62% reduction in colorectal cancer incidence, a more favorable tumor stage at diagnosis, and a 72% reduction in the number of deaths from colorectal cancer in those families, the Blue Ribbon Panel noted in its report.

"Lynch syndrome is the model genetic disease for us to learn how to do precision prevention," said C. Richard Boland, M.D., chief of Gastroenterology at Baylor University Medical Center, at a recent workshop to help plan for a proposed demonstration project.

A Workshop

The 2-day NCI-hosted meeting, held in February 2017, included researchers, physicians, advocates, and patients. They discussed approaches for identifying individuals who have Lynch syndrome, genetic testing and screening, follow-up medical care, and gaps in current knowledge, among other topics.

"The purpose of the meeting was to gather ideas from experts about important issues related to Lynch syndrome and what we should focus on to move the field forward," said Asad Umar, D.V.M., Ph.D., chief of the Gastrointestinal and Other Cancers Research Group in NCI's Division of Cancer Prevention, who co-led the workshop.

The meeting included presentations on recent studies that could help guide future efforts to improve the identification of individuals with Lynch syndrome and health care delivery.

A study in Ohio, for instance, established a statewide program to improve ascertainment of Lynch syndrome among patients with early-onset colorectal cancer. The study authors found a broad spectrum of mutations associated with a predisposition to cancer in addition to mutations associated with Lynch syndrome.

Researchers from the Colon Cancer Family Registry and other registries presented data on the risks associated with mutations in genes linked to Lynch syndrome. Another presentation focused on studies estimating the cost-effectiveness of various approaches to screen individuals for Lynch syndrome.

Other presenters at the workshop shared research on the psychosocial aspects of being diagnosed with Lynch syndrome. The roles of primary care physicians in helping to identify individuals with Lynch syndrome and in providing follow-up medical care were also discussed.

"It was very apparent from the discussions that to develop the optimal program we must look at the whole spectrum of clinical care," said Kathy Helzlsouer, M.D., in NCI's Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences (DCCPS), who co-led the workshop.

"Our challenge is to figure out the best approach to improve the whole process, from the identification of candidates for genetic testing to providing the appropriate follow-up care for individuals with Lynch syndrome and their families," continued Dr. Helzlsouer, who is associate director of the Epidemiology and Genomics Research Program in DCCPS.

Strategies for Identifying Individuals with Lynch Syndrome

A primary goal of the demonstration project would be to explore new ways to identify individuals with Lynch syndrome and improve their early detection and screening options. A recent study estimated that about 1 in 280 individuals in the U.S. population is living with the condition, although many are unaware of it.

Lynch syndrome is caused by inherited mutations in a group of genes whose protein products are involved in repairing DNA errors that occur as cells copy DNA in preparation for normal cell division. These genetic mistakes are known as mismatches.

During his opening remarks at the workshop, NCI Acting Director Douglas Lowy, M.D., urged participants to consider new strategies for identifying patients at risk of Lynch syndrome "in a more rapid manner," which could lead to screening more individuals and ultimately save more lives.

Family history, Dr. Lowy noted, has long been used to identify individuals suspected of having Lynch syndrome. For instance, someone from a family with a history of colorectal cancers occurring at a relatively early age might consider being tested for Lynch syndrome.

Another approach has been to test the tumors of all patients who develop certain cancers such as colorectal and endometrial—especially at relatively young ages—for a condition known as microsatellite instability, which is much more common in Lynch syndrome-associated tumors than in other tumors. If a patient’s tumor tests positive, then the patient could be tested to see if he or she has inherited a mutation that affects a mismatch repair gene.

Although certain alterations in five genes that are associated with Lynch syndrome can predispose individuals to develop cancer, not everyone with Lynch syndrome will develop cancer. More research is needed to better understand the factors that determine why a carrier of a specific mutation will progress to cancer earlier compared to another, several presenters said.

In addition to being a diagnostic tool, testing tumors for microsatellite instability may inform decisions about treatment. "Immunotherapies have performed well in tumors that test positive for microsatellite instability," said Dr. Umar.

Genetic Testing

The Blue Ribbon Panel’s recommendation was to institute Lynch syndrome testing for all patients diagnosed with colorectal or endometrial cancer, known as universal tumor testing. This is based on recommendations from several professional groups, including the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer.

Once a patient is identified as having Lynch syndrome, family members who are at risk of carrying the mutation can be tested in a process called cascade testing.

At the workshop, participants also discussed additional ways to identify Lynch syndrome carriers before they develop cancer, such as identifying individuals with a family history suggestive of an inherited cancer syndrome and referring them to a genetic counselor for consideration of testing.

Another question was whether to expand genetic testing beyond mismatch repair genes to include additional cancer-related genes. In some studies, patients suspected of having Lynch syndrome have been found to have alterations in a range of cancer predisposition genes not previously linked to the condition.

But the use of DNA sequencing to profile multiple genes can also reveal alterations and variants that may or may not contribute to the risk of Lynch syndrome or other inherited cancer syndromes. These are known as gene variants of uncertain significance.

Sequencing panels of genes or conducting whole genomic sequencing may also reveal gene variants that may be associated with health conditions other than cancer. Participants at the meeting said that it’s not always clear when or how best to communicate such incidental results to patients.

"Individuals who may be receiving genetic counseling and genetic testing are dealing with uncertainty," said Dr. Helzlsouer. "Many aspects of medical care involve uncertainty. But the technology for sequencing DNA is moving faster than our ability to make sense of all of the results just yet."

Finding variants of uncertain clinical significance occurs frequently when testing multiple genes, Dr. Helzlsouer added. "Interpreting the results [of these tests] is complex."

Follow-Up Care

The importance of follow-up medical care, including genetic counseling and regular cancer screening, for individuals diagnosed with an inherited cancer syndrome emerged as a theme of the meeting. "We need to make sure that no one falls through the cracks," said Dr. Umar.

Advocates at the workshop said that care providers will have to make sure people get the support and medical care they need after genetic testing has led to a diagnosis of Lynch syndrome or another inherited cancer syndrome. These individuals are told that they are at increased risk of certain cancers.

Some participants also highlighted the workforce challenges that would result from the identification of many more individuals with suspected or known inherited cancer syndromes, noting that there would be a shortage of certified genetic counselors and medical personnel experienced in the care of these individuals. There would also be a need for better coordination of care across the health care system, the participants added.

In a presentation about living with Lynch syndrome, Andi Dwyer, director of health promotion at Fight Colorectal Cancer, stressed the importance of addressing the psychosocial needs of individuals diagnosed with Lynch syndrome and their family members. Some of these individuals "talk about how scared they are," said Dwyer, noting that many experience shame and guilt as they communicate the diagnosis of the syndrome to relatives.

Extending Care

As participants at the workshop discussed the potential demonstration project, several researchers pointed out the need to develop a strategy that could be successful across the country, including in places where access to health care may vary. Smaller studies conducted in certain regions or states, such as the aforementioned study in Ohio or in rural areas, could inform how to improve care in diverse health care settings, several participants said.

"We need to learn how to extend improvements in care to all 50 states, where there are different health care settings and insurance coverage issues," said Dr. Umar. If the practice of universal testing of tumor tissue were implemented, for instance, most patients with colorectal cancer would be treated in community hospitals rather than at NCI-Designated Cancer Centers. Community hospitals have variable resources, and the strategy would need to take this into account, Dr. Umar added.

For such a project, primary care physicians would play a critical role, by helping to identify individuals to test and ensuring that these individuals receive the appropriate genetic counseling, testing, screening, and follow-up care.

But primary care physicians have limited time and resources, and they have to address a large range of pressing health issues with patients, including, for example, the opioid epidemic, several presenters noted. Without additional resources and guidance, these physicians may be unlikely to spend time educating themselves and their patients about inherited cancer syndromes, they added.

An Opportunity

Upcoming Cancer Moonshot Funding Opportunity

In the coming months, NCI will release new funding opportunity announcements (FOAs) that address the goals of the Cancer Moonshot. Learn more about the upcoming FOA on approaches to identify and care for individuals with inherited cancer syndromes.

In the coming months, NCI will release new funding opportunity announcements (FOAs) that address the goals of the Cancer Moonshot. Learn more about the upcoming FOA on approaches to identify and care for individuals with inherited cancer syndromes.

Dr. Helzlsouer has received "very positive feedback" from participants of the workshop. For her, the opportunity to conduct research to improve all aspects of care for patients with Lynch syndrome and other inherited cancer syndromes is exciting.

"We have a system for identifying and screening individuals with Lynch syndrome right now," she said. "But I'm optimistic that health care delivery research will lead to approaches that work across multiple systems and improve our ability to identify those at high risk of cancer better than the current system does. And that will help more people."

.png)

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario