Fusobacterium May Help Colorectal Cancer Grow and Spread

December 29, 2017, by NCI Staff

A bacterial species found in the human stomach and intestines may have important implications for treating colorectal cancer, according to new laboratory research.

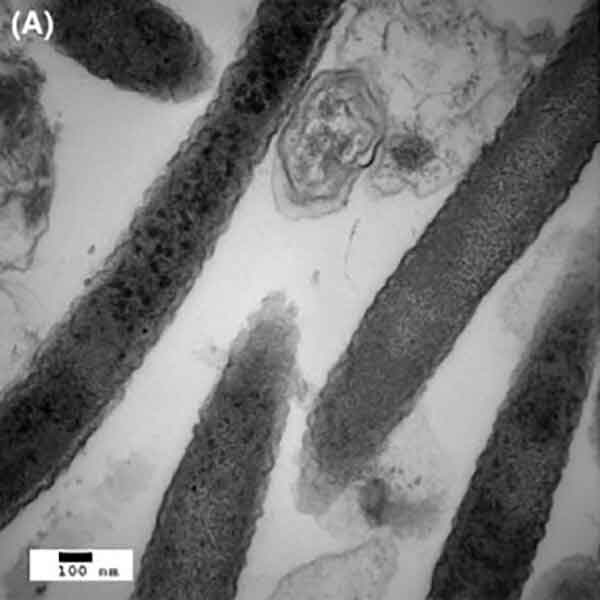

The researchers found that the bacteria not only live in close contact with tumors in the colon and rectum but also reside in metastatic colorectal tumors elsewhere in the body. When the researchers used antibiotics to kill these bacteria in a mouse model of colorectal cancer, tumor growth slowed.

These results hint at the therapeutic potential of targeting microbes as part of treatment for certain types of cancer, explained Matthew Meyerson, M.D., Ph.D., director of cancer genomics at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and senior author of the study.

"We think of tumors as being composed of cancer cells [only], but tumors consist of cancer cells, non-cancer cells, and associated microbes," and therapeutic regimens may need to target all members of these cellular communities to be most effective, explained Dr. Meyerson.

The NCI-funded study was published December 15 in Science.

Reducing Bacteria, Suppressing Tumor-Cell Growth

Previous research from several laboratories identified the bacterial species, called Fusobacterium nucleatum, as one of the most prevalent in colorectal tumors.

To see whether Fusobacterium is also found at sites in the body where colorectal cancer has spread, the research team performed whole-genome sequencing on frozen tissue samples from primary tumors and liver metastases from 11 patients. Of these, seven had Fusobacterium DNA in both the primary and metastatic tumors.

Several other species of bacteria often found living with Fusobacterium were also detected in both primary and metastatic tumors and in similar proportions at both sites, suggesting a stable microbial community centered around Fusobacterium, wrote the authors.

Intriguingly, explained Dr. Meyerson, the DNA sequences of the Fusobacterium at the primary and metastatic sites were nearly identical within individual patients. This suggests that the bacteria may be travelling with cancer cells through the bloodstream to the sites of metastasis, instead of new Fusobacterium cells joining the metastatic cells at their distant sites, he said.

The research team then created a new mouse model of colorectal cancer using tissue taken from patients whose tumors harbored Fusobacterium and other associated bacterial species. The tumors in the mice maintained the microbiome from the human tumors.

To test how antibiotic treatment might impact tumor growth, the researchers treated these mice with erythromicin, which does not kill Fusobacterium, or metronidazole, which does. Erythromycin had no effect on the growth of Fusobacterium-positive tumors, but metronidazole reduced both the number of Fusobacterium in tumors and the rate of tumor cell proliferation and tumor growth.

A Potential New Target for Colorectal Cancer Treatment

The exact nature of the relationship between colorectal cancer cells and Fusobacterium is still under study, although researchers suspect that it’s a mutually beneficial one, said Dr. Meyerson.

"The tumors are [likely] benefiting from Fusobacterium—the Fusobacterium may be providing essential nutrients or growth signals to the tumor," explained Phillip Daschner, a program director with NCI's Division of Cancer Biology who was not involved with the study. "And the tumor appears to be providing the Fusobacterium with a suitable, immune-protected niche that helps it colonize and grow within the gastrointestinal tract," he added.

The study results suggest that Fusobacterium may be "a possible new target for treating colorectal cancer," Daschner said.

Potential antibiotic approaches to killing Fusobacterium in patients with colorectal cancer would need to be very specific, explained Dr. Meyerson. Broad-spectrum drugs could kill beneficial species of bacteria in the body as well, which could harm patients and even affect the response to cancer therapy in ways we do not yet understand.

"We each have a very complicated microbiome in our body," said Dr. Meyerson. "There's a normal balance to that microbiome, and to some extent a normal microbiome protects us."

If an approach to specifically killing Fusobacterium could destroy only the cancer-associated community of bacteria, "then maybe that would impact the cancer without having a lot of impact on the rest of the [body's] microbiome," he concluded.

Bacteria May Play a Role in Chemotherapy Resistance

In a study published September 15 in Science, an international team of researchers funded in part by NCI found that several species of bacteria can break down the chemotherapy drug gemcitabine (Gemzar®), rendering it useless. In a mouse model where such bacteria had colonized colon cancer xenografts, the antibiotic ciprofloxacin restored tumors’ sensitivity to gemcitabine.

Because gemcitabine is commonly used in the treatment of pancreatic cancer, the researchers looked at the prevalence of bacteria in pancreatic tumor samples from patients. They found that, out of 113 samples tested, 76% tested positive for any type of bacteria. And out of a set 15 bacteria-positive samples that underwent further analysis, 93% contained bacteria that, in laboratory experiments, were found to confer complete resistance to gemcitabine.

"The presence of bacteria in human tumors may paradoxically result in drug concentrations that are lower in the tumor than in other organs," wrote the authors. Because chemotherapy sensitivity could be restored with antibiotic treatment in their experiments, they concluded that such combination therapy is worth exploring in further research.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario