Late Effects of Treatment for Childhood Cancer (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version

General Information About Late Effects of Treatment for Childhood Cancer

During the past five decades, dramatic progress has been made in the development of curative therapy for pediatric malignancies. Long-term survival into adulthood is the expectation for more than 80% of children with access to contemporary therapies for pediatric malignancies.[1] The therapy responsible for this survival can also produce adverse long-term health-related outcomes, referred to as late effects, which manifest months to years after completion of cancer treatment.

A variety of approaches have been used to advance knowledge about the very long-term morbidity associated with childhood cancer and its contribution to early mortality. These initiatives have utilized a spectrum of resources including investigation of data from the following:

Studies reporting outcomes in survivors who have been well characterized regarding clinical status and treatment exposures, and comprehensively ascertained for specific effects through medical assessments, typically provide the highest quality data to establish the occurrence and risk profiles for late cancer treatment–related toxicity. Regardless of study methodology, it is important to consider selection and participation bias of the cohort studies in the context of the findings reported.

Prevalence of Late Effects in Childhood Cancer Survivors

Late effects are commonly experienced by adults who have survived childhood cancer; the prevalence of late effects increases as time from cancer diagnosis elapses. Multi-institutional and population-based studies support excess hospital-related morbidity among childhood and young adult cancer survivors compared with age- and sex-matched controls.[2,3,7-10]

Research has demonstrated that among adults treated for cancer during childhood, late effects contribute to a high burden of morbidity, including the following:[4-6,11-14]

- 60% to more than 90% develop one or more chronic health conditions.

- 20% to 80% experience severe or life-threatening complications during adulthood.

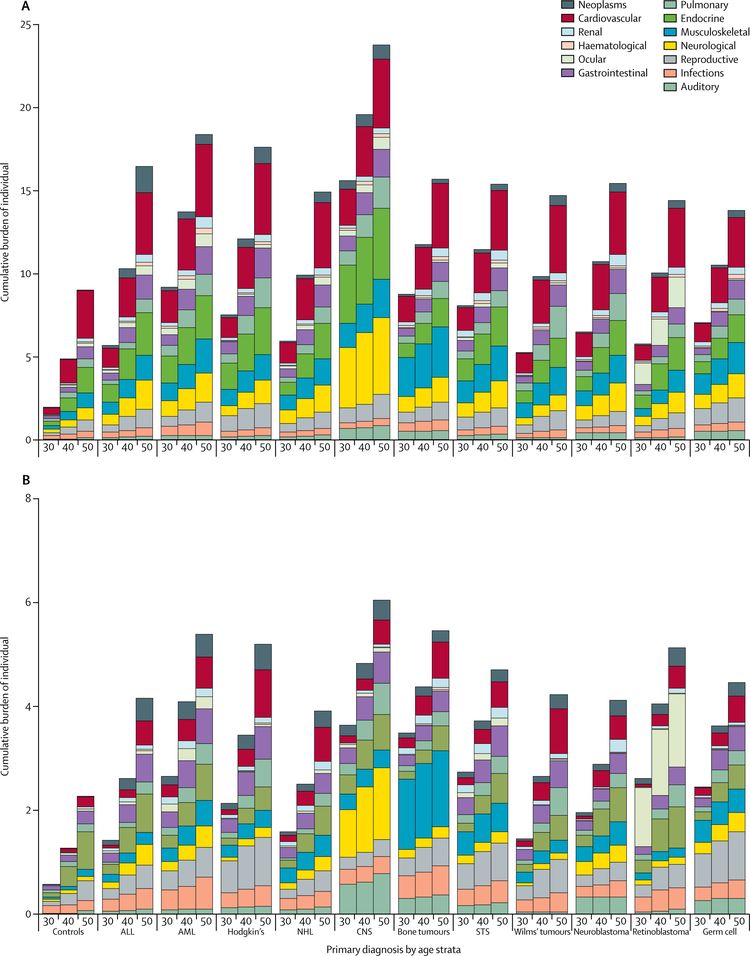

Using the cumulative burden metric—which incorporates multiple health conditions and recurrent events into a single metric that takes into account competing risks—by age 50 years, survivors in the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort experienced an average of 17.1 chronic health conditions, 4.7 of which were severe/disabling, life threatening, or fatal.[13] This is in contrast to the cumulative burden in matched community controls who experienced 9.2 chronic health conditions, 2.3 of which were severe/disabling, life threatening, or fatal (refer to Figure 1).[13]

The variability in prevalence is related to differences in the following:

- Age and follow-up time of the cohorts studied.

- Methods and consistency of assessment (e.g., self-reported vs. risk-based medical evaluations).

- Treatment intensity and treatment era.

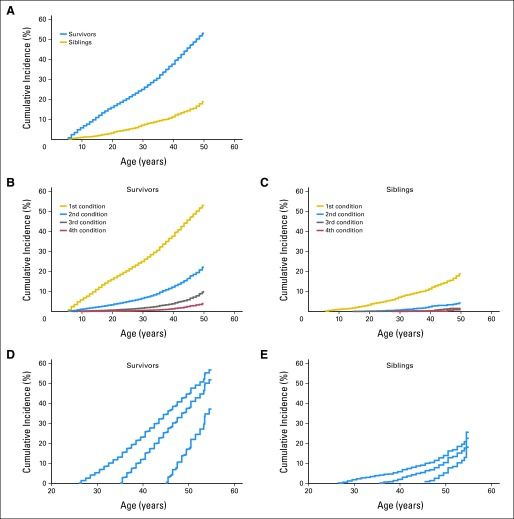

Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) investigators demonstrated that the elevated risk of morbidity and mortality among aging survivors in the cohort increases beyond the fourth decade of life. By age 50 years, the cumulative incidence of a self-reported severe, disabling, life-threatening, or fatal health condition was 53.6% among survivors, compared with 19.8% among a sibling control group. Among survivors who reached age 35 years without a previous severe, disabling, life-threatening, or fatal health condition, 25.9% experienced a new grade 3 to grade 5 health condition within 10 years, compared with 6.0% of healthy siblings (refer to Figure 2).[4]

The presence of serious, disabling, and life-threatening chronic health conditions adversely affects the health status of aging survivors, with the greatest impact on functional impairment and activity limitations. Predictably, chronic health conditions have been reported to contribute to a higher prevalence of emotional distress symptoms in adult survivors than in population controls.[15] Female survivors demonstrate a steeper trajectory of age-dependent decline in health status than do male survivors.[16] The even-higher prevalence of late effects among cohorts evaluated by clinical assessments is related to the subclinical and undiagnosed conditions detected by screening and surveillance measures.[6]

CCSS investigators also evaluated the impact of race and ethnicity on late outcomes by comparing late mortality, subsequent neoplasms, and chronic health conditions in Hispanic (n = 750) and non-Hispanic black (n = 694) participants with those in non-Hispanic white participants (n = 12,397).[17] The following results were observed:

- Cancer treatment did not account for disparities in mortality, chronic health conditions, or subsequent neoplasms observed among the groups.

- Differences in socioeconomic status and cardiovascular risk factors affected risk. All-cause mortality was higher among non-Hispanic black participants than among other groups, but this difference disappeared after adjustment for socioeconomic status.

- Risk of developing diabetes was elevated among racial/ethnic minority groups even after adjustment for socioeconomic status and obesity.

- Non-Hispanic blacks had a higher likelihood of reporting cardiac conditions, but this risk diminished after adjusting for cardiovascular risk factors.

- Nonmelanoma skin cancer was not reported by non-Hispanic blacks, a finding that has been replicated by other studies,[18] and Hispanic participants had a lower risk than did non-Hispanic white participants.

Recognition of late effects, concurrent with advances in cancer biology, radiological sciences, and supportive care, has resulted in a change in the prevalence and spectrum of treatment effects. In an effort to reduce and prevent late effects, contemporary therapy for most pediatric malignancies has evolved to a risk-adapted approach that is assigned on the basis of a variety of clinical, biological, and sometimes genetic factors. The CCSS reported that with decreased cumulative dose and frequency of therapeutic radiation use over treatment decades from 1970 to 1999, survivors have experienced a significant decrease in risk of subsequent neoplasms.[19] With the exception of survivors requiring intensive multimodality therapy for refractory/relapsed malignancies, life-threatening treatment effects are relatively uncommon after contemporary therapy in early follow-up (up to 10 years after diagnosis). However, survivors still frequently experience life-altering morbidity related to effects of cancer treatment on endocrine, reproductive, musculoskeletal, and neurologic function.

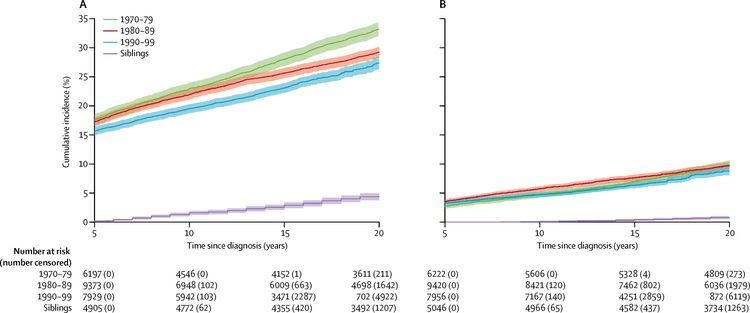

A CCSS investigation examined temporal patterns in the cumulative incidence of severe to fatal chronic health conditions among survivors treated from 1970 to 1999. The 20-year cumulative incidence of at least one grade 3 to 5 chronic condition decreased significantly, from 33.2% for survivors diagnosed between 1970 and 1979, to 29.3% for those diagnosed between 1980 and 1989, to 27.5% for those diagnosed between 1990 and 1999, compared with a 4.6% incidence in a sibling cohort. The overall decrease in incidence of chronic conditions across the three treatment decades was, in part, because of a substantial reduction of endocrinopathies, subsequent malignant neoplasms, musculoskeletal conditions, and gastrointestinal conditions, whereas the cumulative incidence of hearing loss increased during this time. Declines in morbidity were not uniform across the diagnosis groups or condition types because of differences in treatment and survival patterns over time (refer to Figure 3 for more information).[20] Despite declines in chronic health conditions over time, self-reported health status has not improved in more recent treatment eras; this finding may be because of the survival of children with higher-risk disease who would have previously died of cancer in earlier eras, or an enhanced awareness of and surveillance for late effects among more-recently treated survivors.[21]

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario