Thursday, November 19, 2015

THURSDAY, Nov. 19, 2015 (HealthDay News) -- Heart failure patients who had beads of gel injected into their beating hearts continue to show improvement in their health a year after undergoing the procedure, researchers report.

About 85 percent of patients who received the gel implants displayed only slight or no limitations in physical activity during a one-year follow-up, compared with only 25 percent of patients in a comparable control group.

Blood oxygen levels also continue to improve in these patients, and they are able to walk hundreds of feet farther, said lead researcher Dr. Douglas Mann, chief of the cardiovascular division at Washington University School of Medicine and a cardiologist-in-chief at Barnes Jewish Hospital in St. Louis.

The findings from a clinical trial update were published recently in the European Journal of Heart Failure.

Based on these results, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has authorized a larger-scale clinical trial of Algisyl-LVR. It will involve 240 patients with advanced heart failure, Mann announced last week at the American Heart Association meeting in Orlando, Fla.

Heart experts at the meeting said the initial results appear impressive, but they also expressed concern over the death rate among patients who received the gel implants.

"We really need to iron out the mortality risk associated with this device," said Dr. Lori Mosca, director of preventive cardiology at New York-Presbyterian Hospital and medical director of the Columbia University Center for Heart Disease Prevention in New York City.

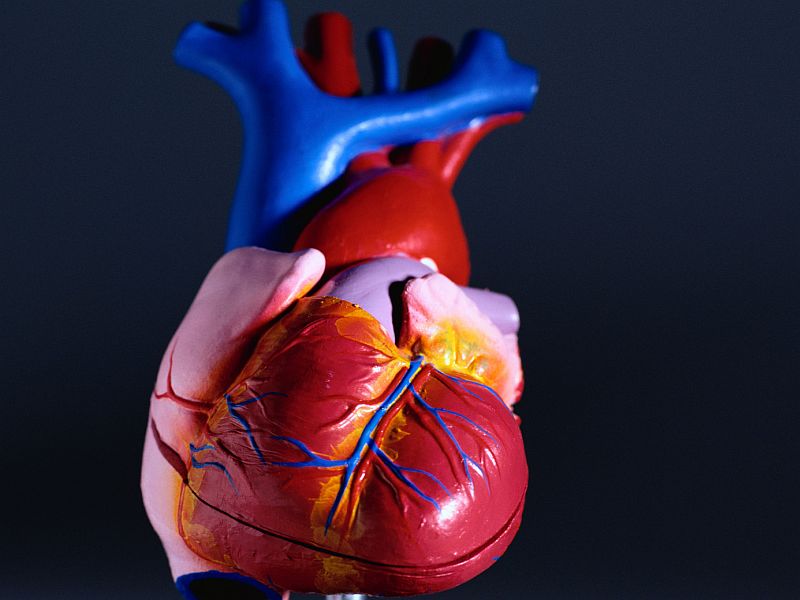

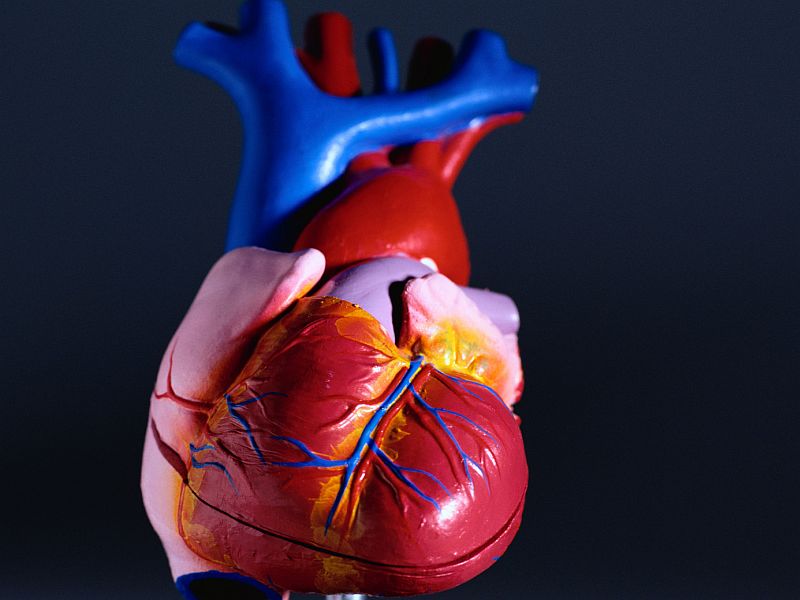

Of the 5.7 million Americans living with heart failure, about 10 percent have advanced heart failure, according to the American Heart Association. Heart failure means the heart isn't pumping blood as well as it should. The condition is considered advanced when conventional treatments no longer work, and patients feel shortness of breath and other symptoms even when resting.

Algisyl-LVR is intended to shore up weakened heart walls, which are a major contributor to severe heart failure, Mann said.

As heart walls weaken, the heart's chambers balloon out, which compromises the heart's efficiency and increases the risk of congestive heart failure, irregular heart rhythms, strokes and heart attacks, Mann said.

"By injecting this gel into the wall and thickening it, one will reduce wall stress because you're increasing wall thickness," Mann said. The goal is to return the heart to a more naturally healthy shape.

The gel is described as an "injectable proprietary biopolymer" by its maker, Texas-based LoneStar Heart Inc., which funded the clinical trial.

In this trial, 35 patients with advanced heart failure received the gel implant while 38 received the standard medical therapy. The procedure can be performed in a beating heart and does not require bypass surgery.

It took about 80 minutes to implant an average of 15 gel beads into each patient's heart wall. The patients spent about two days in intensive care recuperating after the surgery, Mann said.

During the subsequent year, blood oxygen levels have steadily risen in the gel implant patients, while decreasing in the control group, the researchers reported.

Patients treated with Algisyl were nearly 32 times more likely to have experienced significant improvement in their functional ability, compared to the control group, the investigators found.

The implant patients also were able to walk 330 feet farther than the other patients in a six-minute walk test, according to the study.

However, more patients died in the implant group than the control group. There were four deaths (11 percent) in the control group, compared with 9 deaths (22.5 percent) in the Algisyl group.

Although the death-rate numbers are troubling, Mann and other experts at the heart association meeting said that it's hard to assess mortality rates in small-scale trials. The larger FDA-approved trial will provide a clearer picture of the risks associated with the gel implants, he said.

Mann said researchers also are investigating improvements to the procedure, mainly by figuring out a way to inject the beads using a catheter snaked through the blood vessels and into the heart. Currently, surgeons have to crack open the chest to inject the gel.

"This is now a fairly invasive procedure, and I think it would be much more palatable to patients if it can be performed endoscopically," Mosca said.

SOURCES: Douglas Mann, M.D., chief, cardiovascular division, Washington University School of Medicine, and cardiologist-in-chief, Barnes Jewish Hospital, St. Louis; Lori Mosca, M.D., director, preventive cardiology, New York-Presbyterian Hospital and medical director, Columbia University Center for Heart Disease Prevention, New York City; Nov. 11, 2015, European Journal of Heart Failure

HealthDay

Copyright (c) 2015 HealthDay. All rights reserved.

- More Health News on:

- Heart Failure

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario